Schiff Violated The Law • (Don Jr didn't)

Whistleblower Outing Accusation From ‘View’ Co-Host

Bounces Off Trump Jr., Lands On Schiff

A look into the allegations that Don Jr. broke the law retweeting the name of the purported whistleblower raises additional questions about legal liability for Adam Schiff’s own conduct.

On the other day’s episode of “The View,” co-host and ABC senior legal analyst Sunny Hostin combatively accused Donald Trump Jr., saying “It is a federal crime [for him] to out a whistleblower.” After a swift rebuttal by Trump Jr., a back and forth ensued, with Hostin finally claiming that under 18 USC § 1505 “it is a crime,” dramatically flashing her legal credentials by saying, “My law degree says it is.” Oh?

It’s easy to believe there could be a federal law against such a thing, given that our government seems to have criminalized nearly everything, but what does that statute actually say?

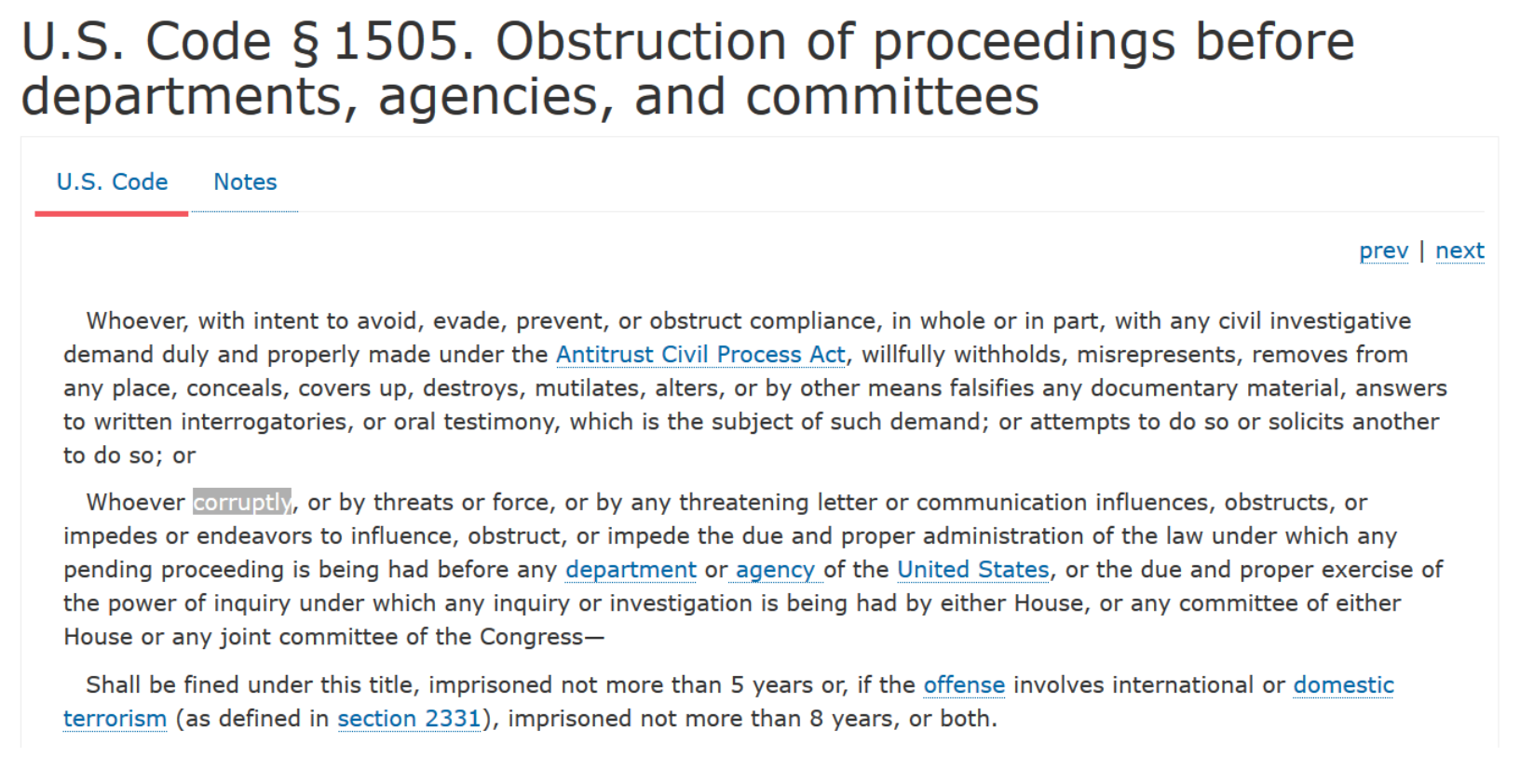

18 U.S. Code § 1505 relates to “Obstruction of proceedings before departments, agencies, and committees.” A variety of conduct is outlawed in the section, all geared toward ensuring the integrity of government processes and proceedings. Presumably, her linking this statute to the alleged “outing” of the purported whistleblower is based on the legal theory that the outing is tantamount to intimidation of a witness that would “corruptly influence a pending proceeding.”

Setting aside House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff’s latest assurances that the whistleblower does not need to testify and thus is not a witness who could be intimidated anyway, let’s examine the alleged linkage.

Whoever corruptly, or by threats or force, or by any threatening letter or communication influences, obstructs, or impedes or endeavors to influence, obstruct, or impede the due and proper administration of the law under which any pending proceeding is being had before any department or agency of the United States, or the due and proper exercise of the power of inquiry under which any inquiry or investigation is being had by either House, or any committee of either House or any joint committee of the Congress…

Is Retweeting Acting Corruptly?

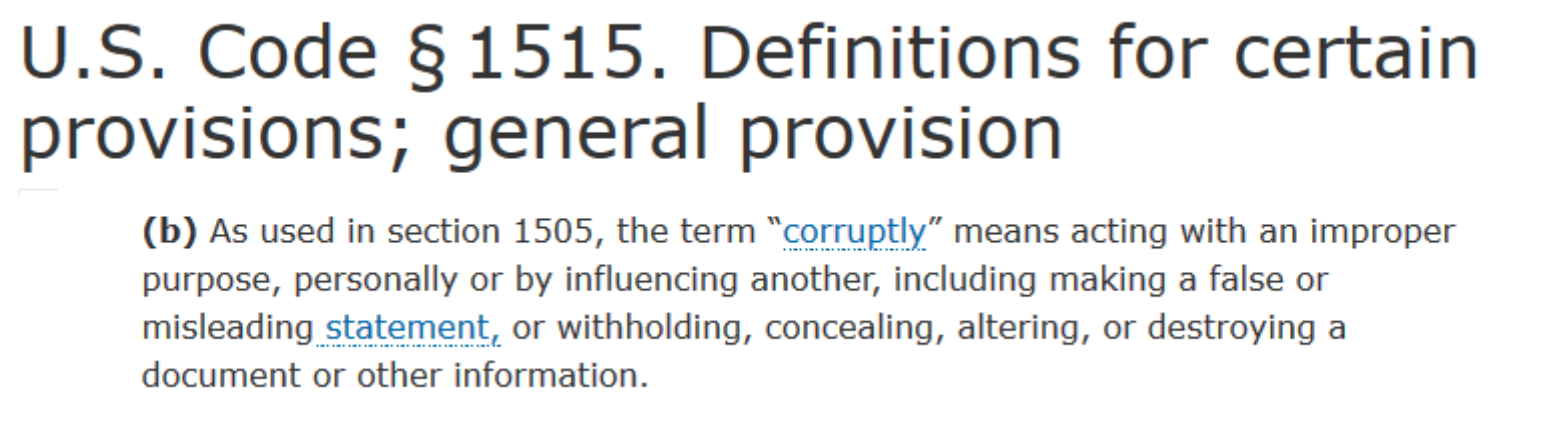

One’s view of what defines “corruptly” is likely guided by his predisposition toward the entire whistleblower saga, but Congress actually defined “corruptly” as it pertains to 18 USC § 1505 when it enacted a clarifying amendment to 18 USC § 1515 via the False Statements Accountability Act of 1996.

(b) As used in section 1505, the term ‘corruptly’ means acting with an improper purpose, personally or by influencing another, including making a false or misleading statement, or withholding, concealing, altering, or destroying a document or other information.

While “improper purpose” may still raise an eyebrow for those looking to find a way to criminalize the “outing” of the purported whistleblower, this too is a dry well, as Congress’ legislative intent makes clear. The clarifying language in H.R. 3166 in the 104th Congress was added in the Senate by unanimous consent, then accepted in the House unanimously under the heading “CLARIFYING PROHIBITION ON OBSTRUCTING CONGRESS.” Thus it’s hard to imagine Congress intended to criminalize a tweet, especially it if wasn’t “false or misleading.”

The President Suggests Schiff Acted Criminally

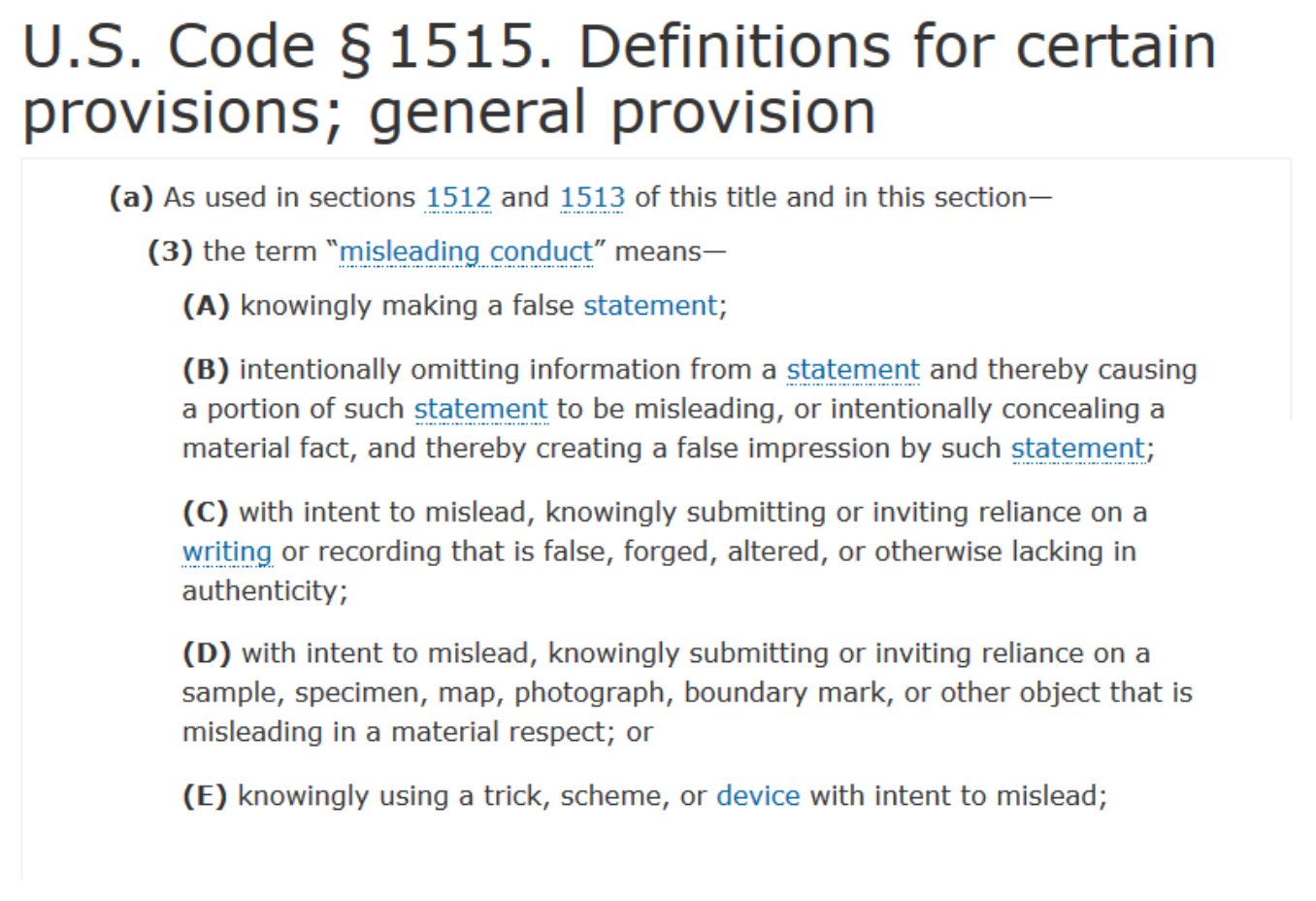

Ironically, the statute’s clear prohibition of “misleading” conduct before a proceeding of “any committee of either House” seems to place Schiff in the hot seat once again. Maybe President Trump’s tweet alleging it was a crime for Schiff to “parody” Trump’s call with President Zelensky of Ukraine wasn’t so far-fetched after all.

It’s hard to argue that Schiff’s manufactured opening statement doesn’t violate each one of the five criteria: He acknowledged it was untrue, it intentionally created a false impression, he invited reliance upon it, it was misleading in a material respect, and it was most certainly an intentional trick or scheme. But is he liable for this misleading conduct?

Legislative Immunity Is Not Absolute

The “Speech or Debate Clause” in the U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Sec 6, does provide for the legislative immunity of certain statements — including false ones — and the contemporary understanding of most is that a member of Congress can say anything as long as he or she says it in an official capacity. However, that’s an overly broad interpretation of the Constitution as the Supreme Court itself noted in Gravel v. United States, 408 U.S. 606 (1972) (i.e., the Pentagon Papers case):

Article I, § 6, cl. 1, as we have emphasized, does not purport to confer a general exemption upon Members of Congress from liability or process in criminal cases. Quite the contrary is true. While the Speech or Debate Clause recognizes speech, voting, and other legislative acts as exempt from liability that might otherwise attach, it does not privilege either Senator or aide to violate an otherwise valid criminal law in preparing for or implementing legislative acts.

The definition of a “protected legislative act” isn’t clearly defined, but the Supreme Court opinion quoted approvingly from the lower court, which had noted its applicability was not absolute: “As the Court of Appeals put it, the courts have extended the privilege to matters beyond pure speech or debate in either House, but ‘only when necessary to prevent indirect impairment of such deliberations.’ United States v. Doe, 455 F.2d at 760.”

The court also affirmed that unless actions were “essential to legislating,” they were not necessarily protected. In making this distinction, the court referenced an earlier opinion stating that certain “acts are no more essential to legislating than the conduct held unprotected in United States v. Johnson383 U.S. 169 (1966).”

The Johnson case also brings up the contours of legislative immunity and just how broad the Constitution should be construed. While the Johnson opinion generally held that a bribery prosecution of a congressman dependent solely on his floor speech would be contravened by the “Speech or Debate Clause,” the court stressed that it was a limited ruling, placing a deliberate marker regarding restrictions to this immunity:

[W]e expressly leave open for consideration when the case arises a prosecution which, though possibly entailing inquiry into legislative acts or motivations, is founded upon a narrowly drawn statute passed by Congress in the exercise of its legislative power to regulate the conduct of its members.

Despite what we often see, there are no carve-outs and exemptions for members of Congress, as the language in 18 USC § 1505 intentionally uses “whoever” to convey applicability of the law. Other than the broadly inclusive applicability, the statute is narrowly written and purports to regulate any conduct before congressional proceedings, making a strong case that Congress intended to regulate its own conduct as well as everyone else’s.

So is Congress subject to the aptly named False Statements Accountability Act of 1996, unanimously passed by both chambers and signed by President Bill Clinton 30 years after the Supreme Court opinion in Gravel? According to the Supreme Court, it at least appears to be “open for consideration.”

Post a Comment