Is This Mysterious Text the Most Ancient Hebrew Book Ever Discovered?

Found in a cave in Afghanistan, the parchment dates to between 660 and 780 CE. Soon, it will be on display at the Museum of the Bible.

In 2019 a curator from the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., and an elderly scholar from Jerusalem were at work on an odd manuscript: a pocket-sized Hebrew book of uncertain age and origin.

Over the years, the manuscript had been variously identified as a fragment of the Talmud, a seventeenth-century book of Psalms, a relic from Babylon, a ninth-century prayer book, and a remnant of a famous medieval repository of texts from a synagogue in Cairo.

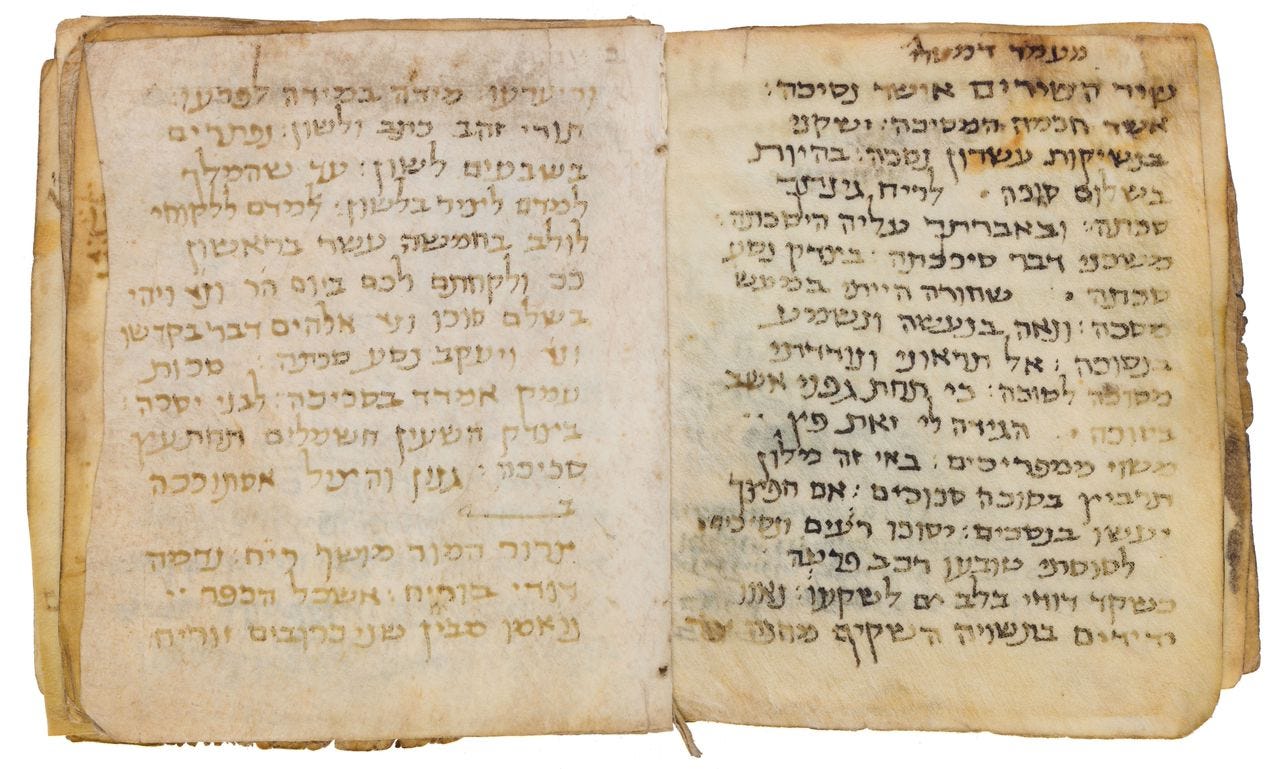

It was rare enough to draw the attention of scholars, if not the public. Some of the pages contained a previously unknown poem for the Jewish festival of Sukkot. On one page, an untrained scribe, perhaps a child practicing lessons, wrote out the Hebrew alphabet. Other pages had a version of the Haggadah, the text read by Jewish families at the festive Passover meal.

The Jerusalem scholar, Malachi Beit-Arié, had a hunch that the book’s story was other, and older, than it seemed.

Beit-Arié, 82 at the time, was one of the world’s preeminent authorities on Hebrew manuscripts, and his hunches were taken seriously. (He died four years later, in 2023.) The research team sent four parchment fragments for carbon dating, then waited for several months in suspense.

When the radiometric results finally came back from the lab, they proved him right: The parchment dated to between 660 and 780 CE. This result didn’t mean a minor chronological adjustment. It meant that the mysterious little book had just been catapulted into a different league of antiquities.

The new date meant that the text of the Passover Haggadah wasn’t just ancient—it was the most ancient known to scholars. The book predated the first standardized Jewish siddur, or prayer book, by more than a century. The research team was holding, in fact, the oldest bound Hebrew book ever discovered.

When the little prayer book goes on display at the Museum of the Bible at the end of this month, it will be accompanied by a new origin story pieced together in years of sleuthing by one of the museum’s curators, Herschel Hepler. Parts of the puzzle—as won’t surprise anyone familiar with the market in ancient books of great value—remain opaque.

There are more ancient Hebrew texts written on scrolls, most famously the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are about 2,000 years old, and were found in the Judean desert in the mid-twentiethth century. But though Jews may be known as people of the book, they actually started using bound books relatively late, around 1,300 years ago.

By this time, the bound book, known technically as a codex, had been used for centuries by Romans and Christians. The codex has the advantage of allowing a scribe to use both sides of the parchment, and also lets a reader easily flip around inside a text, unlike the more unwieldy scroll, which must be unfurled or rolled. Jewish tradition grudgingly saw the advantage of the invention, though never entirely came around—to this day, rabbinic law requires that the Torah be read in synagogue from a scroll written by hand.

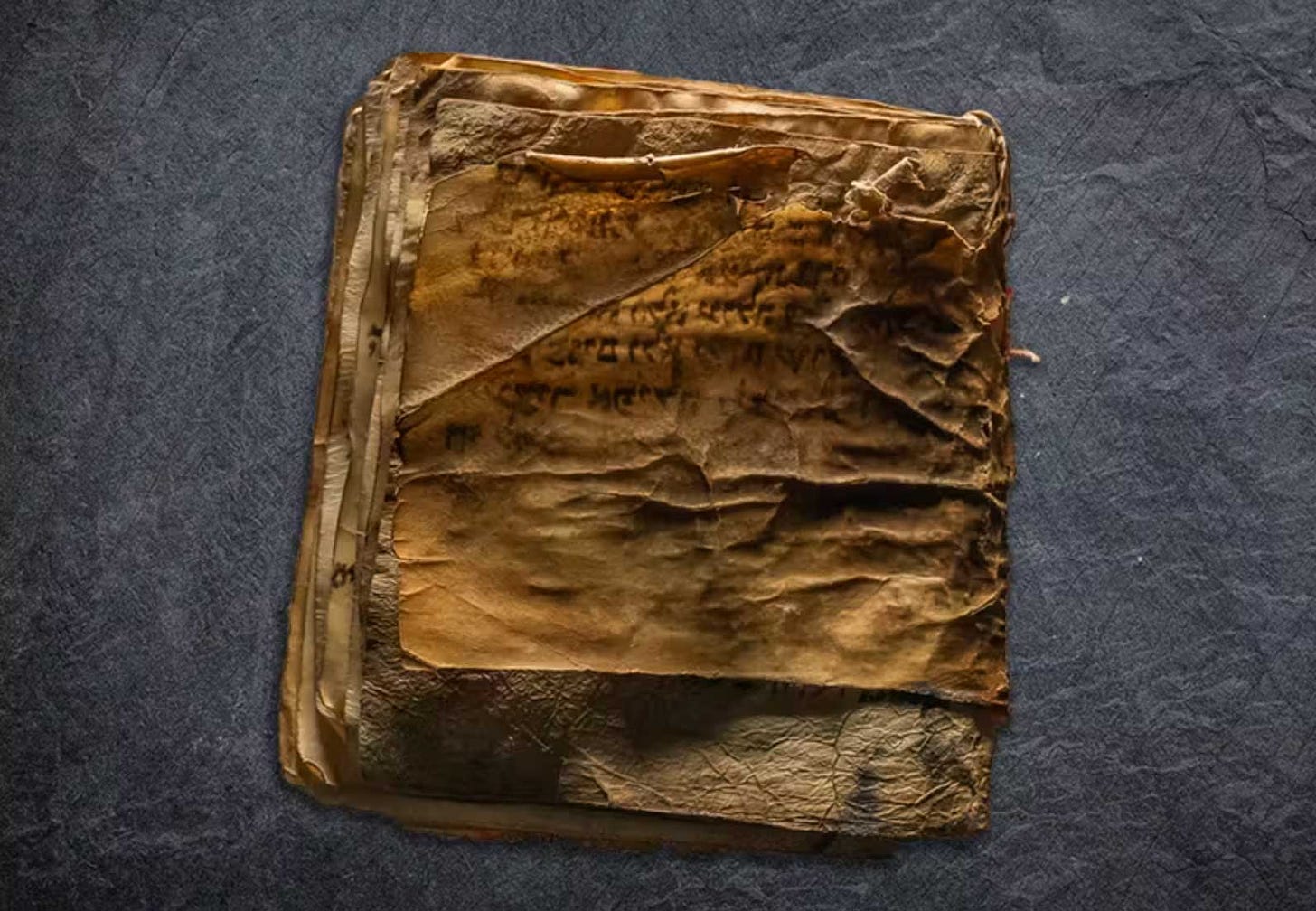

The codex, measuring five inches by five inches, was already in the museum’s collection when Hepler began investigating it. The D.C. museum originated in the private collection of the Green family of Oklahoma, owners of the Hobby Lobby chain and evangelical Christians who became enthusiastic collectors of biblical antiquities. The book had been purchased by Hobby Lobby, according to museum records, from an Israeli dealer in 2013, and misidentified as coming from “Egypt, circa. 900 CE.” It was briefly displayed at a Jerusalem museum the following year.

Scholars were already asking questions about lacunae in the book’s biography, and Hepler began looking more closely at its origins. The scene of his key discovery was, of all places, not the Bodleian Library at Oxford or the recesses of the Sotheby’s archive but the online Jewish publication Tablet, where he happened upon a 2012 story about Jewish manuscripts surfacing in a completely different part of the world, the mountains of Afghanistan.

Reading the article, he was startled to see a photograph of a familiar object. Here the codex was identified as a “sixteenth- to seventeenth-century Hebrew book of Psalms,” but it was the same size and had the same text written in exactly the same script. It was the same book.

The photo turned out to have been taken by the article’s author, Afghanistan expert Jonathan Lee, in 1998. The book’s true place of origin, it seemed, was not Cairo, or Babylon, as some scholars thought, but Bamiyan, in the Hindu Kush 80 miles northwest of Kabul.

Bamiyan served for centuries as a stop along the great east-west trading routes known collectively as the Silk Road, and unlikely as this may seem now, Jews once lived here as a minority, not among Muslims but among Buddhists. At the same time the book was made by artisans cutting, folding, and binding animal skins in the 700s CE, Islam was surging across the region from Arabia, but had yet to conquer these mountains.

With the help of Lee, the expert who’d fortuitously photographed the book in Bamiyan, the curator ascertained that the manuscript was found in 1997 by a Hazara man, member of an ethnic group that has suffered persecution and massacre at the hands of the Sunni fundamentalists of the Taliban. At the time, the Taliban were besieging the Hazara enclave, which would fall in terrible bloodshed the following year.

A member of the Hazara militia Hizb-i Wahdat, the man—identified only by the pseudonym “Hasan”—was moving munitions between caves when he happened upon the book.

The caves around Bamiyan are part of the ruins of the Buddhist civilization that once thrived there before Islam. The precise location of the cave in question is known to the research team, Hepler said, but is being kept secret to avoid looting. He would say only that it’s close to the larger of the two giant Bamiyan Buddhas that were sculpted from the mountain in the sixth century and infamously blown up by the Taliban in 2001.

Other ancient Jewish texts have surfaced in Afghanistan in recent decades—most notably a trove of documents dating to between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries and linked to a trading family named Abu Netzer. Many of these documents were purchased by Israel’s National Library in 2016. But even the oldest of them are still more than 200 years younger than this book.

It seems noteworthy that other unique manuscripts have survived in precisely the same remote area: In 2006, for example, a team of German archaeologists found a Buddhist Sanskrit manuscript hidden inside one of the two Bamiyan Buddhas. “There seems to be a regional element in play here,” Hepler, the curator, told me. “This was a place where books were protected and revered as sacred.”

The little book may have been kept by a Jewish family in Bamiyan, the curator suggested, with different people adding new texts as the years passed. The hands of at least five scribes are evident in the pages. They were influenced by ideas and writing coming from both major Jewish centers of the time—Babylon, which is modern-day Iraq, and the Land of Israel, where Jewish sovereignty had been lost seven centuries before and whose people were now under Islamic rule.

The previously unknown poem shows the influence of a familiar biblical text, the erotic Song of Songs, according to Professor Shulamit Elizur of the Hebrew University, the member of the research team in charge of the poem’s analysis. But it also shows the impact of an esoteric Jewish book that wasn’t part of the Bible, known as the Apocalypse of Zerubbabel. This book is thought to have originated in the early 600s, when a brutal war between Byzantium and the Sasanian empire of Persia generated desperate messianic hopes among many Jews. Whoever wrote the poem in the Afghan prayer book had clearly read the Apocalypse, Elizur said—giving us a glimpse of a Jewish spiritual world both familiar and foreign to the coreligionists of the Bamiyan Jews in our own times, 1,300 years later.

Chapters of the book’s journey from Afghanistan to Washington are unclear—some because they’re simply unknown even to the experts, and others because that’s the way the people in the murky manuscript market often prefer it.

When the book was discovered by the Hazara militiaman, according to Hepler, the tribesmen didn’t know exactly what it was but understood it was Jewish and assumed it was sacred. The local leader had it wrapped in cloth and preserved in a special box. At one point in the late 1990s, it seems to have been offered unsuccessfully for sale in Dallas, Texas, though it’s unclear if the book itself actually left Afghanistan at the time.

After the al-Qaeda attacks of 9/11 triggered the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the book disappeared for about a decade. In 2012 it resurfaced in London, where it was photographed by the collector and dealer Lenny Wolfe.

Any story about Afghan manuscripts ends up leading to Wolfe, an Israeli born in Glasgow, Scotland. I went to see him at his office in Jerusalem, an Ottoman-era basement where the tables and couches are cluttered with ancient Greek flasks and Hebrew coins minted in the Jewish revolt against Rome in the 130s CE. It was Wolfe who helped facilitate the sale of the larger Afghan collection to Israel’s National Library. “The Afghan documents are fascinating,” he told me, “because they give us a window into Jewish life on the very edge of the Jewish world, on the border with China.”

When Wolfe encountered the little prayer book, he told me it had already been on the London market for several years without finding a buyer. In 2012, the year he photographed the book, he said it was offered to him at a price of $120,000 by two sellers, one Arab and the other Persian. But the Israeli institution he hoped would buy the book turned it down, he told me, so the sale never happened.

Not long afterwards, according to his account, he heard that buyers representing the Green family had paid $2.5 million. When I asked what explained the difference in price, he answered, “greed,” and wouldn’t say more. (Hepler of the Museum of the Bible wouldn’t divulge the purchase price or the estimated value of the manuscript, but said Wolfe’s figure was “wrong.”)

The collection amassed by the Green family eventually became the Museum of the Bible, which opened in Washington in 2017. The museum has been sensitive to criticism related to the provenance of its artifacts since a scandal erupted involving thousands of antiquities that turned out to have been looted or improperly acquired in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East.

The museum’s founder, Steve Green, has said he first began collecting as an enthusiast, not an expert, and was taken in by some of the dubious characters who populate the antiquities market. “I trusted the wrong people to guide me, and unwittingly dealt with unscrupulous dealers in those early years,” he said after a federal investigation. In March 2020 the museum agreed to repatriate 11,000 artifacts to Iraq and Egypt.

Curators operating in the modern world of antiquities must grapple with frequent demands for objects to be returned to their country of origin, calls that are sometimes justified but often more complicated than they seem. The idea that the modern Arab-Muslim dictatorship in Egypt, for example, has an automatic claim to 3,000-year-old treasures of the non-Arab and non-Muslim pharaohs is not straightforward. And these civilizational treasures can often be better cared for elsewhere: The national museums of Egypt, Iraq, and Afghanistan, for example, have all been looted in the wars and revolutions of the twenty-first century.

Hepler, the curator, refers to the Museum of the Bible as the “custodian” of the Afghan codex, and is careful to emphasize that officials of the democratically elected Afghan government have been involved in its study and exhibition. That government was toppled and replaced by the Taliban after the American withdrawal in 2021, so a repatriation request from that direction isn’t likely. And the community that produced the book no longer exists in Afghanistan—there’s some debate about the identity of the country’s last Jew, but whoever he or she was, they left in 2021.

Today, you’re most likely to meet Afghan Jews in Israel or Queens, New York. For them, a manuscript kept in Washington, D.C., is accessible, while one in Afghanistan is not. I asked Wolfe, the collector and dealer, what he thought. “Material culture, prima facie, belongs in the place where it was created and found,” he said. “More than that it belongs to the people who sincerely care for it. Therefore, it should not be repatriated.”

Much of what Afghanistan was can now be found elsewhere. To evoke the world from which the book came, for example, the Afghan codex is displayed at the Washington museum near another exile—a bust of the Buddha from a site near the city of Jalalabad.

The bust was a gift to President John F. Kennedy from the king of Afghanistan, Mohammad Zahir Shah, in 1963, before he was overthrown and exiled himself.

https://www.thefp.com/p/mysterious-text?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=260347&post_id=148813028&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=false&r=rd3ao&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

Post a Comment