The FBI, the IG Report, and Attorney General Barr – Separating fact from fiction

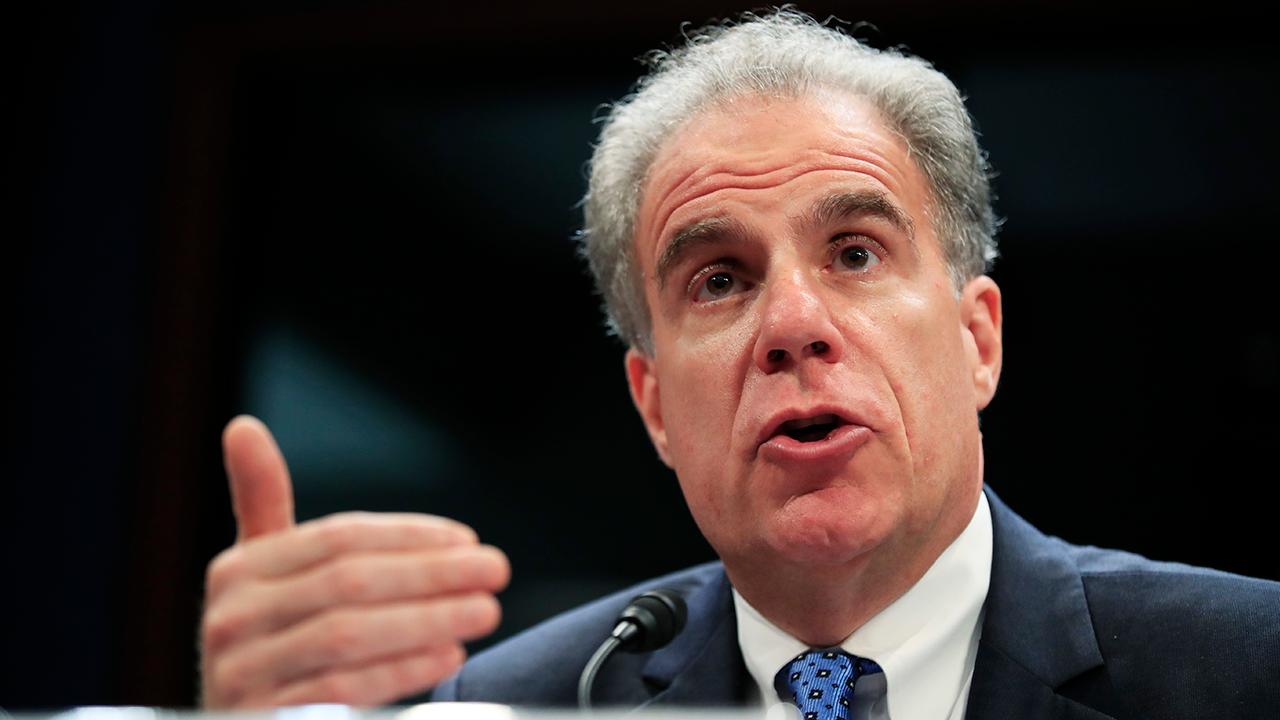

Andy McCarthy, former U.S. Assistant Attorney, weighs in on the Horowitz IG report and if the Obama administration spied on the Trump campaign

There are many things to be said about the 476-page FISA abuse report filed by Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz – too many to say in a single column. So we’ll try to take them in small bites. Let’s start with an IG’s finding that the FBI’s Trump-Russia investigation was properly “predicated.”

To understand what (as in how little) the report actually says on predication, Horowitz’s two baseline assumptions must be considered.

First, regarding the quantum of fact-based suspicion necessary before an investigation may properly be opened, the FBI sets the bar so low it is illusory.

Essentially, a hunch will do for purposes of opening a preliminary investigation. Something only slightly less nebulous, such as a suspicion that can be articulated reasonably (though not convincingly), will do for a full-blown investigation.

The idea is that, **legally,** the FBI must be given the widest of berths to enforce the law and protect national security. Practically, the expectation is that the agency’s focus will be confined to serious cases, not bogus ones, due to the guidance of its supervisors.

Second, it is not the IG’s job to review discretionary judgments by government officials, only to determine if laws, rules, policies, or procedures have been violated.

The interplay between these two assumptions renders meaningless the IG’s determination that the investigation was properly predicated.

Essentially, the IG is saying that, underwritten procedures rather than day-to-day common sense, there are no significant impediments to the FBI’s opening of any investigation.

Sure, there are a few obvious no-nos. A probe may not be opened, even preliminarily, based on invidious discrimination (race, ethnicity, religion, sexual preference, etc.). It must not be opened for a non-law-enforcement or national security reason – e.g., an agent may not snoop around financial institutions because he’s curious about how much money his neighbors make.

But there’s not much more to it than that. If a person of no known background, or even a track record of deception, tips an FBI agent that Donald Trump is an agent of the Kremlin, the IG is not going to say it would be improper for the FBI to poke around.

He is apt to accept the Bureau’s self-serving claim that, even if the grounds of suspicion were not strong, the nature of the allegation was so disturbing that it would have been irresponsible not to investigate.

Logically, of course, that means no allegation, no matter how thinly supported, is beyond the pale if it sounds sensational enough.

Add to that the IG’s caveat that reviewing discretionary decisions is not in his purview. In other words, as long as judgment calls are made within the context of a case that has been opened legitimately (as that concept is forgivingly defined in FBI regs), it is not the IG’s function to assess those judgment calls – including the decision to open the investigation in the first place.

The IG is not there to tell us whether a decision was appropriate, much less prudent, or at least carefully considered. If the predication is adequate, then the IG tells us he cannot second-guess the investigation’s commencement.

As a result, the IG may not (or at least does not) tell us the only thing that matters: Was it appropriate under the circumstances to open an investigation of the Trump campaign?

This is the nub of Attorney General William Barr’s disagreement with the report.

We have a norm in the United States against the incumbent administration’s use of the government’s intelligence and law-enforcement apparatus in the service of domestic politics.

Moreover, counterintelligence powers, which are vital to protecting our nation from terrorist attacks, hinge on public and congressional support. They will lose that support if they are exploited for political purposes.

Consequently, if the FBI is going to breach that norm, it must have strong evidence to believe a political campaign is conspiring with a foreign power.

That is Barr’s point. He is not talking about what the FBI may do in a run-of-the-mill case under its ever-elastic predication guidelines. He is talking about what it must do in order to make responsible decisions in light of the stakes involved.

The Horowitz review does not account for that. It simply says the investigation was properly predicated under the FBI’s low-bar standards for opening cases.

It does not say it was appropriate for the FBI to open a case on sparse evidence in light of the possibility that the Bureau would interfere in, and potentially even swing, an American election.

Post a Comment