My Decade with Donald Trump

My Decade with Donald Trump He

chased her with hair spray. She saw him get shot. Salena Zito is the

journalist who knows Trump—and his voters—better than anyone.

REPORTER SALENA ZITO INTERVIEWS DONALD TRUMP ON SEPTEMBER 22, 2024 IN PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA. (VIA SHANNON M. VENDITTI)

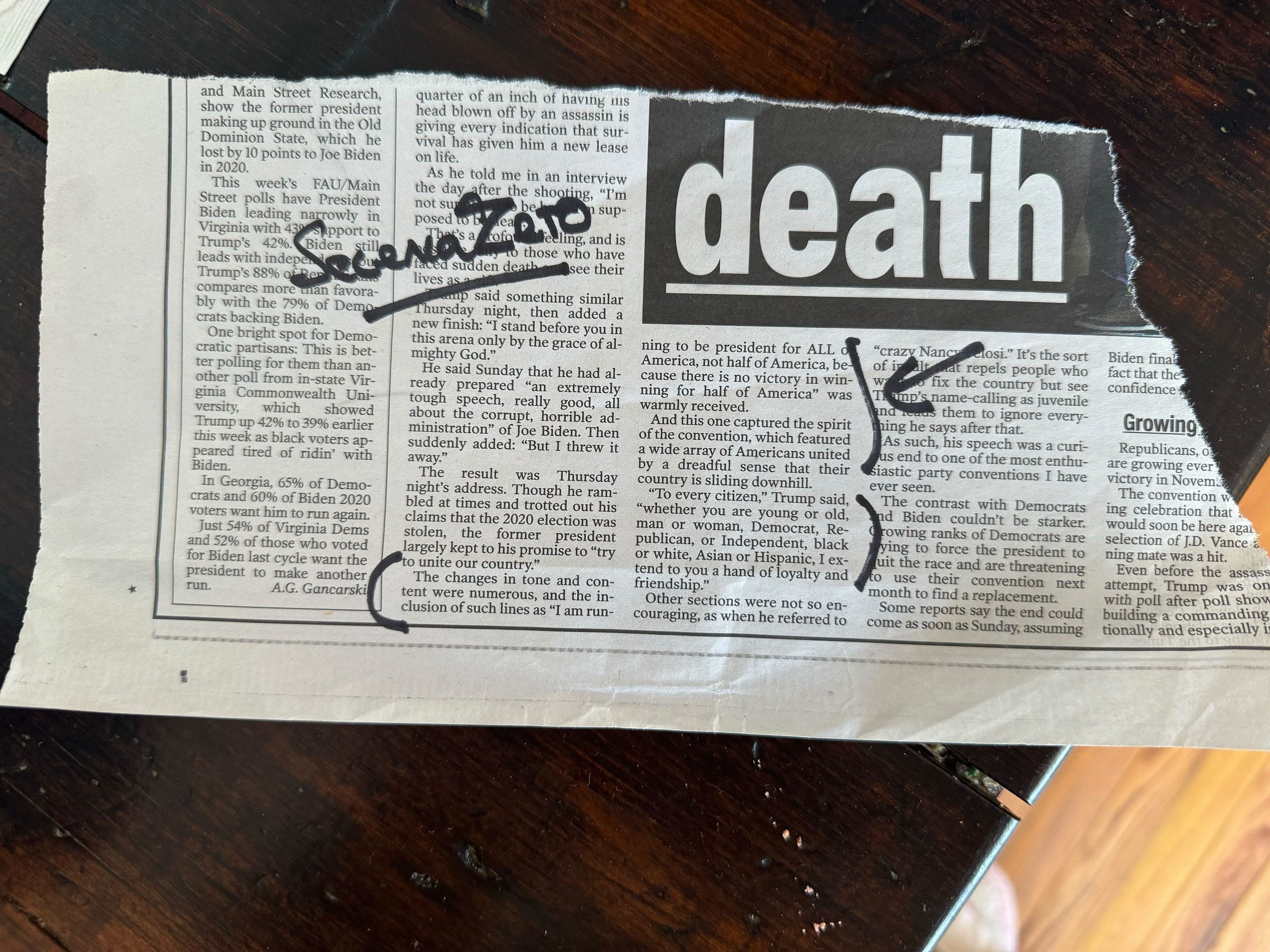

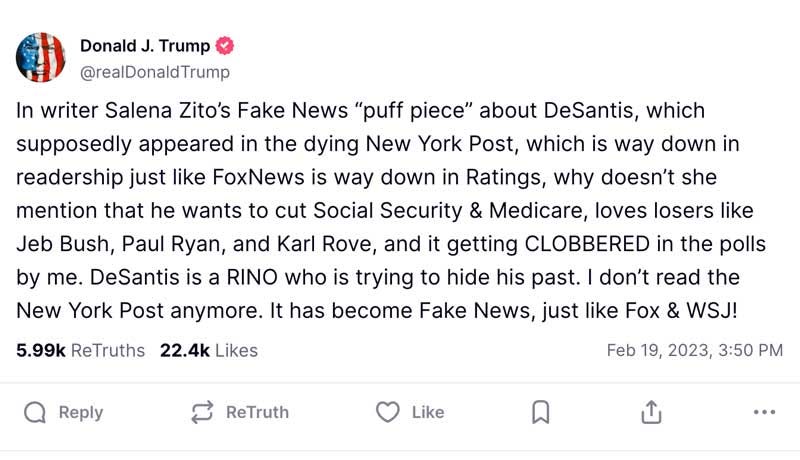

The manila envelope was stamped: From the Office of President-Elect Donald Trump. It arrived with a knock on my front door, a couple of days before Christmas. Inside was a scarlet-red holiday card signed in gold ink, from Melania, Barron, and Donald J. Trump. Enclosed was a page torn out of the New York Post, an article about Trump’s message of unity during his winning campaign. An arrow, drawn in fat black marker, pointed toward three paragraphs in the piece, which referenced the themes of my reporting, and my (misspelled) name was written next to it in all-caps: SELENA ZETO. It was an unexpected greeting, I admit, but by then I’d had many missives like this from the 45th—and soon to be 47th—president. Trump maintains an informal relationship with many journalists, calling them spontaneously or sending them articles ripped out of newspapers with his handwritten thoughts out of the blue. But I guess you could say I know him better than most. I was the only journalist to predict he would win in 2016. My former editor at the New York Post used to call me the “Trump Whisperer.” I am also the reporter who popularized the phrase “the press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.” And I was four feet away when a bullet hit him in 2024. Plenty of journalists have disparaged me for being too sympathetic to Trump. They’ve blasted me for not being critical enough of his crimes, his coarseness, his history with women. But all I’ve ever done is report on what I see. I grew up among his base, and I know why they love him. I was born in western Pennsylvania—in the coal country of Appalachia—and, like most of my ancestors, I never left. Unlike the majority of journalists who write about Trump, I never graduated from college. I’ve been a hairdresser, a waitress, and a shop assistant, and I got into journalism the old-fashioned way. In the late ’90s, when I was a young mother in my 30s, I worked as a staffer for the then–GOP senator Arlen Specter; after that, I became a political journalist for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. That’s where I was working when Trump first announced his candidacy for president. And as he surged in the polls, I found myself wondering how a three-times-married playboy who’s a regular on Howard Stern’s show was becoming so popular with conservatives. In 2016, I covered his campaign stops in Pennsylvania, and I noticed that Trump was visiting parts of the state that nobody else goes to. Forgotten towns like Ambridge and Wilkes-Barre and Johnstown and Butler. Nobody goes to Butler! What I remember most is how Trump came alive on shop floors, speaking to steelworkers, truckers, and plumbers. He really listened to the kind of people who historically voted Democrat. It didn’t surprise me when he got the GOP nomination for president—beating people like Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz. Then, on September 1, 2016, I decided to take a buyout from the paper where I had worked for 11 years, because I figured the next stage would be layoffs. I remember walking out of the building and thinking, I’m 57 years old, and there’s no job for me. Mine wasn’t the only local paper that was shrinking. And then, a couple weeks later, I got a call from one of Trump’s campaign advisers, an old friend I knew from when we worked together for Senator Specter. He said: “Do you want an interview with Trump tomorrow?” I couldn’t believe my luck. The next day, I wore cowboy boots. I remember feeling like my big hair was like a rat’s nest. Trump wore a dark suit. We met in a backstage room at the Shale Insight Conference at Pittsburgh’s main convention center, where he was scheduled to make an appearance to talk about how to Make America Great Again. It was September 22, just six weeks until the election. When I first saw him, he struck me as polite and well-mannered. He made good eye contact and asked me questions about my family, congratulating me on becoming a grandmother. When I asked him about his relationship with the media, he said, “You know, I consider myself to be a nice person. And I am not sure they ever like to talk about that.” Afterward, he took me on a tour of the complex, introducing me to the people there—oil and gas workers from Texas, Colorado, and Pennsylvania. They were all in casual clothing—a lot of flannel, no suits. Trump pumped their hands and asked them questions about what they do, seeming genuinely interested in their answers. I could see how a billionaire could connect with the American working class. People like this worked for him and his father on construction sites and helped build their real estate empire. Also, Trump is not so polished himself. Just before he had to go out onstage, he turned to me and said a line he’s repeated to me so many times in the years since, it’s become a running joke: “Well, I gotta go out there. You want to come out with me?” I just laughed. In the weeks that followed, while the polls showed Hillary Clinton was well in the lead, I traveled throughout the Rust Belt and spoke to voters who convinced me Trump would beat her. The legacy media focused on his rhetoric about Mexicans and Muslims, his behavior toward women, but I knew none of that mattered to the working-class voters who wanted a brawler to stand up for them. I took a lot of flack from other journalists for predicting Trump would win. But I was just relaying what I saw. “People believe he is listening to them,” one voter from East Liverpool, Ohio, told me. “That’s a potent feeling for an area like this.” On Election Day, I was covering a GOP party in Pittsburgh. Trump was still the underdog, but as the results came in, it slowly dawned on everyone that he was cleaning up. By the wee hours of the morning, every Midwestern swing state that was once a Democratic stronghold had gone for Trump. I wasn’t surprised, but I was shocked when I looked around and saw a couple of other journalists tearing up over the results. These were local reporters, who’d spent time among the same voters as I had in Pennsylvania. But they could not understand how Trump could win. The next day, I got a call out of the blue. It was a booker from CNN who wanted me on the air. Immediately, I spat out: “What did I do wrong?” They said: “You’re the only reporter that got it right.” You could say Trump rewarded me for correctly calling the election. My next interaction with him was on the hundredth day of his presidency. His staff had accepted my request to interview him in the Oval Office. He sat at the Resolute desk, and I perched across from him, wearing my cowboy boots. He looked restless, like a caged lion. I could see that D.C. didn’t suit him as much as the shop floor. We talked about the executive orders he had signed, the state leaders he had met. Then he turned to an Andrew Jackson painting behind him, and wondered aloud why more people didn’t ask the question: “Why was there the Civil War? Why could that one not have been worked out?” At the time, the media was obsessed with Russiagate, and desperate to find reasons to delegitimize Trump’s win. So the papers went crazy when I reported those Civil War comments. On CNN the next day, I was asked questions like: “Was he denying there was a Civil War? Or was he denying there should have been a war?” I remember thinking: He was just riffing! This reaction is insane! It had been less than a year since I’d written, “The press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.” This was just one more example of that. It was a while before I met Trump again. In 2018, right before the midterms, I attended his campaign event at a hockey arena in Erie, Pennsylvania. In the green room, an adviser walked me over and said: “President Trump, do you remember Salena?” “Of course I remember Salena,” Trump replied. “She has the best hair in America!” During the interview, we talked about his Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, who had just been grilled during his confirmation hearing over allegations that he had sexually assaulted Christine Blasey Ford. Trump said he was so incensed by the treatment of Kavanaugh that he “didn’t even think about” withdrawing his support. “I felt that it would be a horrible thing not to go through with this,” Trump told me, even though “the easier path” would have been to drop him. After we were done talking, he said: “Come with me.” As he had before, Trump led me toward the stage where he would be speaking. When we got backstage, he pulled back the curtain a little, revealing more than 10,000 people waiting for him to speak. By this point, he’d faced so many crowds like this, but he still seemed delighted by the sight of all these people. “Look out there,” he said to me. “Look at that.” Someone must have spotted him, because a second later, everyone started waving and shouting his name. Trump turned to me and said, again: “You want to come onstage with me?” The next time I met Trump was in May 2020, mid-pandemic. The president was visiting a medical supply company in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to encourage Americans to “stop the spread.” Hundreds had turned out to see him, and although they had to sit six-feet apart, the atmosphere was joyful. I remember the Tom Petty song “Free Fallin’ ” playing on the speakers. People were clapping to the beat. Our interview took place in the stockroom. I was waiting there when I heard his voice booming across the room, asking for me. “Where’s my Salena?!” He was wearing his standard dark suit and a huge smile. I was supposed to stand on a big X on the floor, and he was supposed to stand on an X six-feet away from me. But, of course, he couldn’t keep still and kept wandering off it. He wasn’t wearing a mask—the whole thing about him being a “germaphobe” is bullshit—but I was, and at one point, he just said: “Can you take that off?” I felt a swell of relief, and thought: Thank you. By then, Trump was running for reelection, and Joe Biden had just announced that he was, too. During the interview, Trump slammed Biden’s mental faculties, telling me, “Joe has absolutely no idea what’s happening.” But Biden appealed to just enough blue-collar voters to win the election that year. And in the months that followed, I saw another side of Trump. His lowest point was, of course, January 6, 2021. As I reported in the New York Post, his reckless behavior betrayed his base. I also argued that it jeopardized his political future. It was clear he would run for president again in 2024, but now I thought he didn’t have a chance. As Biden settled into the Oval Office, Trump sank in the polls. His 2022 midterm picks lost their races. I started covering other candidates who I thought could lead the Republican Party forward, including Ron DeSantis. I guess the profile I wrote of the Florida governor kind of irked Trump, because two days after it published, he let me have it with both barrels on Truth Social:

I didn’t respond. I actually found it pretty funny. As a reporter, I don’t care if politicians like me; I care about accurately representing the people whose votes politicians have to earn. And I thought Trump had lost sight of that in that moment. But right after I interviewed DeSantis, there was a train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, which led to a devastating leak of toxic waste. I raced to the scene to talk to the people who lived there. And guess who else was there? Donald J. Trump. He had arrived with two 18-wheelers filled with water bottles, and bought everybody around him McDonald’s. He wandered through the town in galoshes, stepping in puddles. You could see the slime and scum in the water. His appearance that day sent a message that was, essentially, I see you. I’m here for you. I’m not leaving you. I hung back in the crowd and wore a baseball cap over my huge hair, because I knew, this time, he wasn’t going to welcome me with open arms. But I remember scribbling in my notebook that this might be a turning point. As he had in 2016, Trump was showing everyone that he understood America’s forgotten men and women. Soon after, national polls showed he had pulled ahead of the other Republicans vying for the presidential nomination. One year later, on March 12, 2024, he clinched it. Around that same time, I was babysitting my grandchildren when I got a call from a restricted number. I picked it up and was greeted by his buoyant voice. “Hey, Salena, how are you?” I can’t say what we talked about, because it was off the record, but Trump acted like he’d never slammed me on social media. He gave me his cell-phone number, and I filed it under President Donald Trump. I didn’t see him again until a hot day in Butler, Pennsylvania, a few months later. Trump was there for a campaign event, and there was so much anticipation in the air, it felt like a Jimmy Buffett concert—except instead of Parrotheads and Hawaiian shirts, people were wearing stars and stripes. The date was July 13, 2024. Right before Trump was set to appear, I got the nod to come backstage. He was meeting with all these regular people who had been pulled out of the crowd, talking to them and hugging them. Then he saw me. “Salena! Look at that hair! Doesn’t she have the best hair in America?” he boomed. “Look at her hair, everybody.” I wanted to die of embarrassment. He asked about my grandchildren, as usual—and checked I was going to fly to Bedminster, New Jersey, with him after his speech to do a fuller interview. I said I would, and then his aides guided me to a spot four feet away from the podium. I stood next to photographers covering the event, including my photojournalist daughter and her husband. Trump came out. The crowd went wild. I’d seen this happen a hundred times. But then, six minutes in, he did something he never does. He turned to look at a chart that was on the stage, showing how border crossings were at their lowest point ever when he was president. That’s when I heard: Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! I saw Trump grab his ear. Blood streaked across his face, and he ducked down. Later, I realized: If he hadn’t turned to look at that chart for a split second, he would have been killed. Suddenly, everyone was on the ground—including me. A campaign press liaison had leapt on top of me. But I could still see Trump, and hear the entire conversation going on between him and his agents. They were talking about the shooter, saying, “Mr. President, we’ve got to get him.” Then they said, “We have to stand up.” “I gotta get my shoes on,” Trump said. Somehow, they had fallen off in the commotion. I was still on the ground when a man in full camo came over and pointed a gun at four of us on the ground. He must have been part of the president’s security. I was a suspect for a moment. I think everybody was. Then Trump was on his feet. That’s when he defiantly punched the air, in a pose that will go down in history. It was weird how calm and slow everything felt, despite the horror. It felt like we were in a terrible dream. Afterward, we learned that a firefighter, who had two daughters, had been tragically killed by one of the bullets. The next morning, I was sitting at my kitchen table drinking a cup of coffee, when Trump called me and asked: “Salena, are you okay?” And I said, “Mr. President, yes, but are you freaking kidding me? You were just shot, right?” He told me, “I’m so sorry about Corey”—the firefighter who had been killed. “I just want to do right by Corey and his family.” It shook him to think that someone could be killed simply because they had supported him. We ended up having seven different phone conversations that day. He kept getting interrupted, but would call me back. We talked about his decision, in that moment, to raise his fist at the crowd. He said it was important to show that the country is “still strong and we are resilient.” He said he felt like he had an obligation—as a former president—to prove he would never surrender. Trump was back on the road within days. Two weeks later, we met at a rally in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He took me to a back room where there were snacks and a table with a mirror and brushes. We sat on the sofa, facing each other, and he seemed a little different. Humbled, perhaps, by what had almost happened to him. But as I was leaving, his funny side reemerged. “Salena,” he said, “do you use hair spray?” I said, “My hair is big enough, sir.” That’s when he picked up a can of hair spray from his table and started spritzing me with it. I have photos of him chasing me with this spray and laughing, and I just thought: Another crazy day with Donald J. Trump. Up until the election, Trump kept visiting voters throughout Rust Belt Pennsylvania. Westmoreland County, Allegheny County, Armstrong County, Indiana County, and back to Butler County. People lined up to see him in the small towns and big cities, standing on top of buses, trucks, and tractors. Everywhere, there were road closures. I’ve never seen anything like it. I thought: It’s over, right? It’s totally over. I knew Kamala Harris was never going to be elected. Though she arguably won the single presidential debate, when I talked to the voters around me, they didn’t care. They felt they didn’t know her. Trump, they knew. On election night, the results came in fast. I texted him: I told you you’d win Pennsylvania. I didn’t hear back from him—until I got that Christmas card. This Monday, Trump will be sworn in as the 47th president in Washington, D.C. I won’t be there. The best way for me to cover Trump, or any elected official, has always been on my home turf, listening to the people who put him in office. And, this time around, I hope the media takes him less literally. Although I think everyone takes him pretty seriously by now. —As told to Margi Conklin |

Post a Comment