Portland’s Once-Flourishing Downtown, After 2020’s Anti-Police Riots, Emerges as an Abandoned Wasteland of Drug-Using Vagrants, Vandalism, and Missing Statues

Portland ‘hasn’t hit the bottom yet,’ says one real estate analyst.

Portland, long known as a hub of liberal eccentricity, is struggling with the consequences of the pandemic, as well as from the aftermath of 56 straight nights of anti-police rioting in the summer of 2020. Almost four years on, the city that prides itself on “being weird” and was one of the country’s most desirable (and expensive) places to live, is now wounded by vandalism, vagrancy, and squalor. Crime, addiction, and homelessness have been amplified by an exodus of businesses and people from the city’s breaking heart.

Portland’s Plaza Blocks are the heart of the city’s downtown. They consist of two square block plazas featuring monuments underneath towering evergreens and bigleaf maple trees planted at the turn of the 20th century. Once the parks would have been, like the surrounding offices and federal courthouses, vibrant and bustling during the day. Archived Google Street photos from April 2019 show people walking through the parks and lounging on the benches.

Four years after the so-called nationwide “racial reckoning” of 2020, during which anti-police rioting and rampant vandalism hit downtown Portland, the parks, and the rest of the city, are suffering. Today, Lownsdale and Chapman Squares, which make up the two center plazas, sit largely empty but for camped-out vagrants. The squares’ iconic statues, which were heavily vandalized and removed during the 2020 protests, have yet to be restored or replaced.

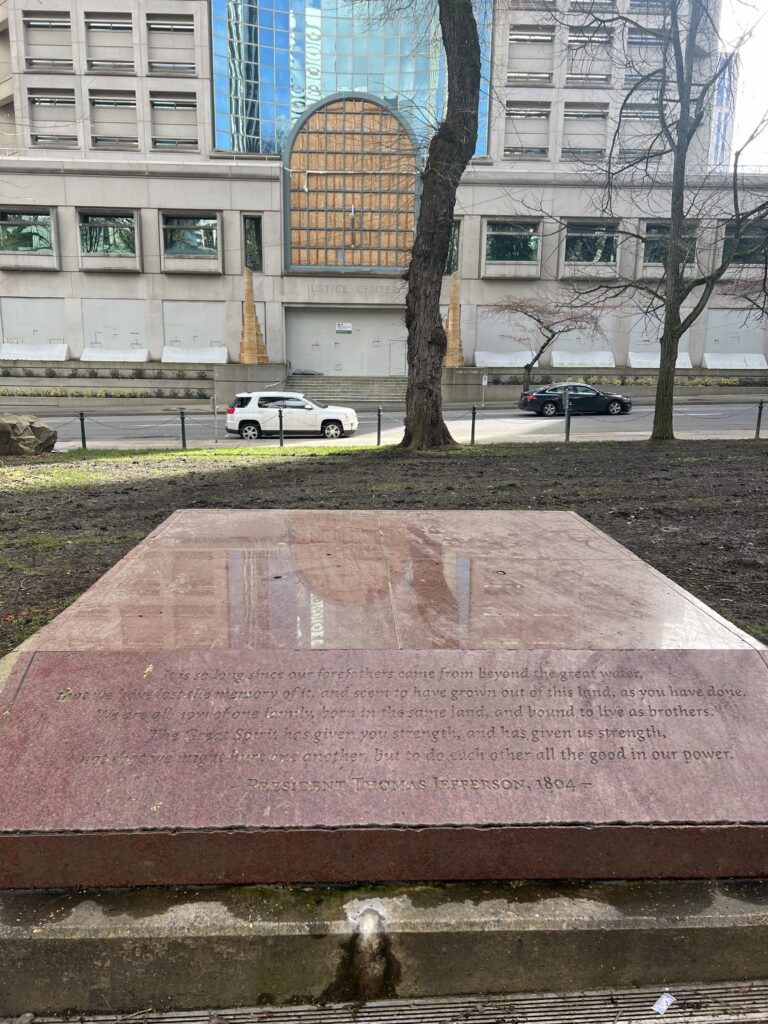

A sculpture of a pioneer family, known as “Promised Land,” is now represented by an empty base. That base, inscribed with a quote from Thomas Jefferson, has escaped its own removal, despite vandalism targeting the Founding Father’s statue at a nearby high school. All that remains of a 120-year-old fountain featuring an elk is a mound of gravel. The fountain was removed in 2020 after damage from protesters made it a safety hazard.

An ornate brick public bathroom to the west of the park, which has since been closed, now has recent “Free Gaza” messages scrawled on its locked door.

The state of Portland’s Plaza Parks is emblematic of the decay noticeable throughout the Rose City’s downtown. Progressive reforms and civil strife have hollowed the area into a shell of what was once an eccentric and “indie” district.

A March report by real estate brokerage firm, Colliers, detailed how the downtown’s vacancy rate, at around 32 percent, is now the highest of the 50 largest downtown office markets in the nation. Colliers’ estimate is higher than that of other real estate firms, which have used different boundaries to define downtown.

In a statement to the Oregonian on Monday, one of the analysts who crafted the report, Jamison Shields, added that, “Unlike other markets that are starting to see a turnaround, Portland hasn’t hit the bottom yet.” The Colliers analysts expect vacancy rates to rise to 40 percent by next year. When asked by the outlet about the main causes of the downturn, he identified, “public safety, crime, lack of cleanliness and high taxes, which have made the city among the most expensive taxing districts in the nation.”

Not all of Portland is derelict. New developments, such as a converted industrial space known as Slabtown, appear relatively healthy, as do the suburbs across the Columbia River, which are void of most of the Rose City’s progressive mores. In these neighborhoods, storefronts are occupied, young children and women freely walk the streets, often with a leashed dog in tow, and crime is less of a factor. An urban expert on the city’s planning and development, Chet Orloff, tells the Sun that the stereotype of Portland as a “Portlandia” of far-left extremism is misplaced.

“The reaction of so many blaming [Portland] for its political stance is garbage,” he said. “It’s a minor issue.”

According to Mr. Orloff, the city has, for the majority of its history, been quite conservative, albeit with an enduring element of technocratic optimism. But the growing influence of a small progressive bloc has foisted its will on the city in the past 10 to 15 years and is, according to the expert, much to blame for the current crisis.

In the immediate vicinity of the Plaza Parks is a federal courthouse that still stands behind tall chain-link fences put up during 2020’s unrest. Windows in the Multnomah County Justice Center on the adjacent southern block, broken over 2020, have now been replaced with sheets of plywood.

To the west of the park is a mixed-use retail and parking center with retail on the ground level. The ground level once housed the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame. Before 2020, the space was leased by a coffee shop, City Coffee, which was described by restaurant reviewers as a “bustling coffee shop” emblematic of “Portland old-school style.”

Another tenant was a virtual reality studio, Uncharted Realities, that took over the space from a golf store in 2019. Every tenant in 933 South West 3rd Avenue left in 2020 and they have not been replaced in the last three and a half years. Painted-black plyboards now cover the windows. The sidewalks outside these abandoned storefronts are now occupied by camping tents where the homeless live.

The rest of downtown is similarly abandoned. Farther north from the courthouse is Southwest 10th Avenue. Walking by its intersection with Yamhill street, this reporter saw nearly every tenant gone and the sidewalks dominated by homeless persons. Before the pandemic, the block was home to a Subway, a thrift shop, a watch store, an arts novelty boutique, and two cafes.

Today, only the cafes and the arts store remain. The thrift store has been replaced with a marijuana store selling drug paraphernalia (cannabis is legal in Oregon). Though there are many cities in America, particularly on the West Coast, that are suffering from an exodus of business and a rise in drug use and criminality, Portland may stand among the worst.

Mr. Orloff zeroes in on a recent ballot initiative as being a source of the city’s ailments related to drug use and homelessness. “Portlanders have been…quite generous in terms of what we have allowed Portland to become,” he said. “And part of that is due to Measure 110, which basically puts cuffs on various sources for maintaining order, keeping drugs out of illicit hands and all of that.”

Passed by a ballot initiative in November of 2020, Measure 110 reclassified possession of small amounts of drugs, including heroin, methamphetamine, and fentanyl, from a misdemeanor or felony to a Class E civil violation. At the time, advocates, who included a well-funded drug decriminalization organization, Drug Policy Alliance, believed that laissez faire would lead to a safer and healthier city by virtue of more destigmatized access to addiction and recovery services.

Against their expectations, though, drug-overdose deaths increased precipitously. Drug overdose death rates soared by 43 percent in 2021 and have continued climbing since then. According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control, the state’s overdose death rate increased 42 percent in the twelve months preceding September 2023. The state now ranks second in the nation, by some measures, in its rate of illicit drug use.

This month, Oregon’s legislature reversed parts of Measure 110. Starting in September 2024, possession of drugs such as fentanyl and heroin will be classified as a criminal misdemeanor with the potential to carry jail sentences up to six months.

Scenes from Portland’s downtown, which this reporter witnessed, reflected the data on vacancy and homelessness, and were on par with such blighted Northeastern cities as Bridgeport, Connecticut or Camden, New Jersey. Entire buildings lie vacant save for the occasional cafe, salad shop, or novelty bookstore. Foot traffic around the area is homeless and vagrant.

Regarding the issue of homelessness, Mr. Orloff noted that the Rose City was not the only metropolis afflicted but that, “Portland has had more than its spades.” He pointed to the city being “more reluctant to come down harder on people, or to move people off the streets, clean up messes.”

Locals who speak with the Sun point out that many of the vagrants are not local, but are drug addicts who migrated to the state on account of its lax drug laws and inexpensive opiates, such as fentanyl. When this reporter visited, downtown residents were scarce. “Everyone is used to it at this point. Everyone is used to being potentially mugged going back to work,” Axel Hernandez, a resident of the city, told NewsNation.

Critics contend that fear of crime is overblown: crime rates in 2023 across an array of categories were down by double digits. According to a press release issued by the city’s police force in January, the city experienced a 23 percent drop in homicides, a 22 percent drop in overall shootings, and an unspecified drop in other felony crimes, including assault, car theft, and burglary.

But the brightening statistics are belied by a sense of lawlessness that may have contributed to the dearth of pedestrians and retailers. The Portland Business Journal found that as crime worsened, many businesses have simply given up on reporting incidents to police out of hopelessness and fear of insurance rate increases. The root cause of the lawlessness seems to be a lack of enforcement, as Mr. Orloff noted.

A study by the Manhattan Institute released in September found that the Rose City’s 800-man strong police force is less than half that of the “median staffing rate of other major cities.” Without sufficient officers on the street, many business owners have given up on law enforcement.

The owner of three Tamale restaurants, Jaime Soltero, told the Portland Business Journal in September that his concern about increased insurance premiums and risk of losing coverage led him to stop reporting theft. In the week prior to his interview, Mr. Soltero told the Journal that one of his locations had been broken into three times and that he’s “just eating up all those costs.”

Others told the paper that they have given up out of simple desperation. The executive director of Business for a Better Portland, Stephen Green, told the Business Journal that among some on the “property crime side of things” say “there’s a sense that no one’s going to show up for three hours.”

“So why even call?”

Post a Comment