Tchaikovsky Is Canceled

Tchaikovsky Is Canceled

The Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra scrubbed the famed composer from an upcoming program, calling his music "inappropriate at this time."

|

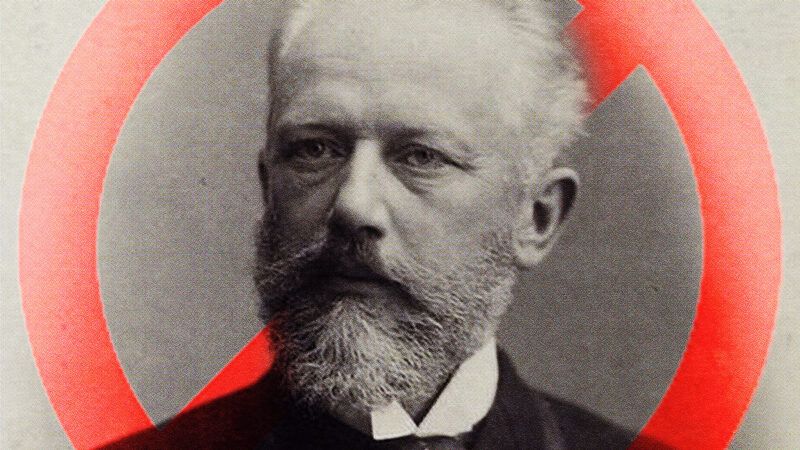

(Illustration: Lex Villena; Wikimedia Commons)

In light of Russia's invasion into Ukraine, many westerners are understandably doing their level best to distance themselves from President Vladimir Putin and those loyal to him. But some of those gestures look increasingly like performance art.

The latest utterly pointless sanction is the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra's announcement that it would remove music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the Russian composer, from its all-Tchaikovsky concert, calling it "inappropriate at this time." In the last week, conductor Valery Gergiev and superstar soprano Anna Netrebko have also lost engagements and artistic affiliations due to their cozy ties to the Russian president.

Nationality and prodigious talent aside, Tchaikovsky shares little else with Gergiev and Netrebko. The latter two are alive and beneficiaries of an autocrat's favoritism; Tchaikovsky died over a century ago.

The composer is an inappropriate scapegoat for another reason: He was one of the first and only Russian composers to eschew Russian nationalism and endear his music to the West, becoming what many historians would consider one of the few bridges between Russian and European artistry.

He also loved Ukraine.

There was plenty of political and public pressure to take the opposite route. Tchaikovsky's primary contemporaries were a group of Russian composers nicknamed "The Five"—Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Alexander Borodin—who dedicated their musical lives to constructing a distinctly Russian-nationalist style. Tchaikovsky was the odd composer out. Having been educated at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, where Western European influences were heavy, he inserted themes from Russian folk tunes but imbued his music with the operatic and balletic lyricism more characteristic to the works of his neighbors.

Perhaps more importantly, his disposition for an international musical style informed the ways in which he shared it with the world. In an era when many Russian composers siloed themselves off from the globe, Tchaikovsky sought to be a part of it; during a three-month tour in 1888, he became the first Russian composer to personally unveil his music to Western Europe. It was on that trip that he met Brahms, the German composer, whose music he disliked and whose popularity he chalked up to a nationalistic sort of fan-girling. Their exchange is an instructive window into how Tchaikovsky wanted his music to be received. It couldn't stand on identity. It just needed to be good.

That left him on the outskirts—an allegory for his life, in some sense, which was marred with depressive episodes as well as inner torment over his homosexuality (the latter of which, I'll add, would not make him very popular in Putin's Russia). At odds with some of the nationalist cultural elite, he gave the premiere of his opera Eugene Onegin to a group of students as opposed to a grand Russian theater. And when Rimsky-Korsakov of "the Five" had an about-face and took a job at the Western-influenced Saint Petersburg Conservatory—seen in some corners as a betrayal of sorts—it was Tchaikovsky who supported him.

Those who agree with the Cardiff Philharmonic's decision to deprogram Tchaikovsky may note that one of the selections on the program was his 1812 Overture, a 15-minute piece celebrating the defeat of Napolean Bonaparte's attempted Russian invasion. The piece is inappropriate given the circumstances, the thinking goes. Such comparisons fall a bit flat when looking at the historical context: The piece does not commemorate Russia as the aggressor but rather as a country successfully fending off a foreign invader; as such, it has been embraced by the West and is familiar to many American audiences during 4th of July celebrations. There are lessons to be learned there.

Even still, the objection hardly necessitates scrubbing Tchaikovsky in his entirety solely because of where he was born. That's especially true in light of what was supposed to be the program's main course: his Symphony No. 2, which, in a sort of cosmic irony, is built around…three Ukrainian folk songs.

For those familiar with Tchaikovsky, that likely won't come as a shock. The composer spent several months a year in Ukraine and had close family ties to the region; his paternal grandfather was born there. "I found the peace of mind here that I had unsuccessfully sought in Moscow and Petersburg," he once wrote, ever the outsider.

Even in death, it appears Tchaikovsky will continue to play that part, the anti-nationalist again ostracized—this time by the people who purport to agree with the core of what he stood for. In a time where some are unable to differentiate between supporting Putin and being Russian, when theaters and embassies are vandalized and defaced solely because of their flag, it's not necessarily a surprise. But that doesn't make it less of a shame.

Post a Comment