Fear the Economic’End of Men’

Fear the Economic ‘End of Men’

Yes, we should be worried about the economic decline of America’s men — to say otherwise is to ignore the facts.

Last month, the Wall Street Journal reported that women now represent a record-setting 60 percent of new enrollees on America’s college campuses. Given the fact that higher education tends to engender brighter economic prospects, today’s abundance of freshwomen relative to freshmen is a recipe for a future in which jobs are more abundant for women than for men. With men’s relative decline potentially in the offing, some have warned of a looming existential crisis to boot. Is this angst merely economic alarmism, or a fear grounded in facts?

Unfortunately, the prophets of doom have the facts on their side. Everyone should be fearful of an economy such as the one the Journal’s report forebodes. In fact, for some Americans, the crisis that accompanies the economic “end of men” has already arrived.

The American communities whose job markets have been heavily exposed to automation preview a future in which men become obsolete at a faster rate than women. Why? Automation in America, research indicates, has destroyed about two jobs for men for every one job that it has destroyed for women. Communities with labor markets that have been upended by advances in robot technology, then, are microcosms of what will happen in the U.S. if men fall behind economically relative to women.

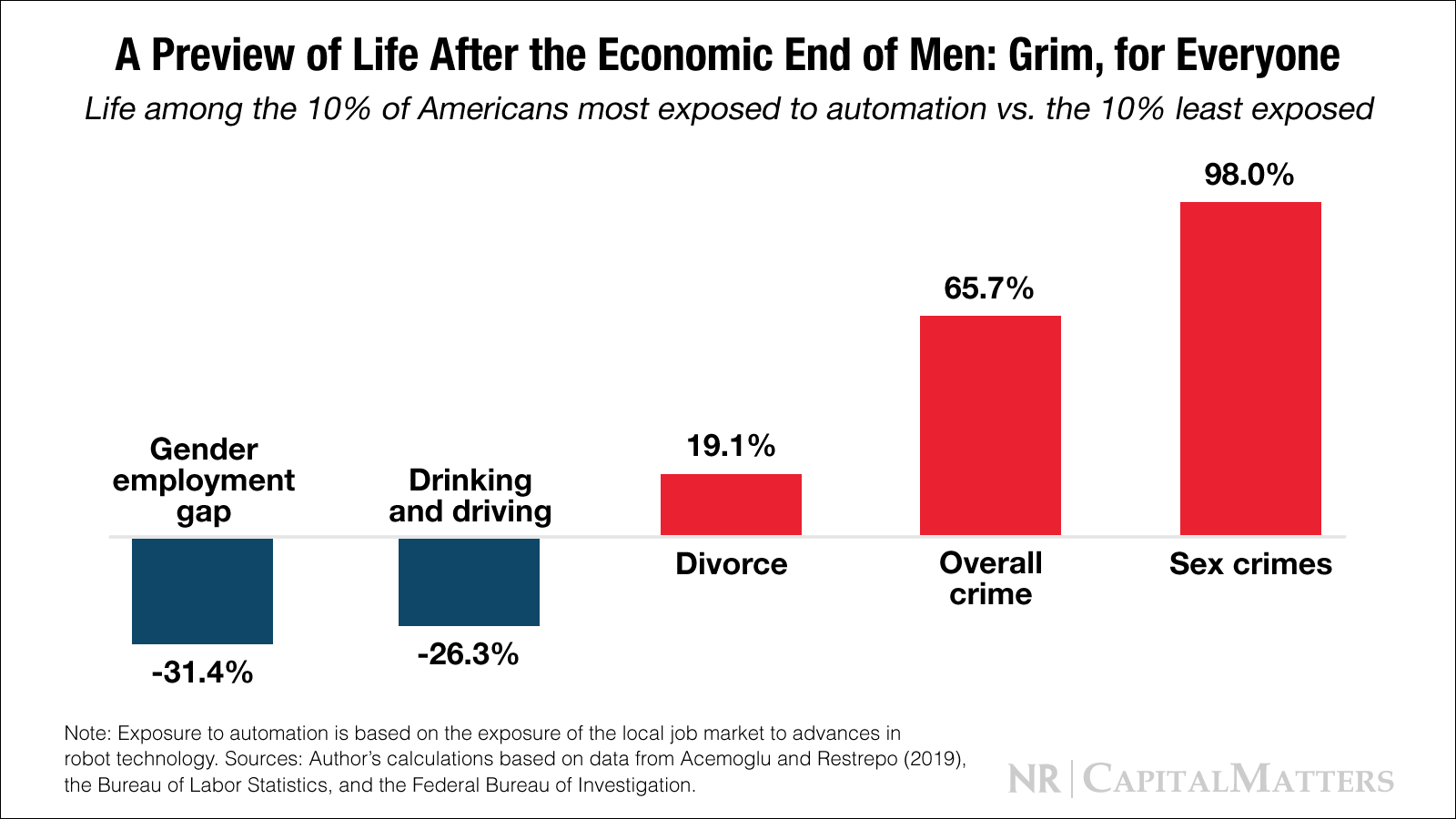

Something akin to a statistical crystal ball, the chart above compares life among the 10 percent of the American population most exposed to automation with life among the 10 percent least exposed.

The relative obsolescence of men does create headline figures that some would welcome. Male and female employment rates do converge. And it should be noted that among the 10 percent of Americans most exposed to automation, the employment-to-population ratio is still higher for men than women. But the employment-to-population-rate disparity between men and women is a whopping 31.4 percent lower than it is among the 10 percent least exposed. There are other consolations from the new employment landscape: In collecting fewer paychecks, for instance, men are less likely to run up bar tabs and make their way into the driver’s seat. Per capita rates of drunk driving, a crime perpetrated by men 80 percent of the time, are 26.3 percent lower among those most exposed to automation. This suggests that the effects of automation may complicate the well-documented tendency of lower rates of employment to, historically, raise local rates of alcohol abuse and other substance abuse.

But this is no happy tale. When marriages are formed, they tend fall apart more frequently. Rates of divorce are 19.1 percent higher among the 10 percent most exposed to automation than among the 10 percent least exposed. Sex crimes, per capita, are a whopping 98 percent higher. Some crimes may grow less frequent, but crime as a whole does not. The per capita rate of crime overall among the most exposed is 65.7 percent higher.

Headlines about women’s share of college enrollment underscore the extent to which “the future is female” is an aphorism likely to prove true, at least within America’s workforce. There is certainly much to celebrate in that. But there is also much to fear about the economic decline of America’s men. To say otherwise, now, is to ignore the facts.

Post a Comment