U.S. nonfarm productivity is a measure of economic activity within the engine of the U.S. economy. The U.S. productivity rate is a measure of how much value is produced by the economy through demand for the products and services, and the labor associated with the creation of those products and services.

I have often used the example of making bread {Go Deep}. If you are making 10 loaves of bread, there is a set amount of cost associated with each loaf created. The total cost of each loaf is the total cost to produce the entire batch divided by ten. However, if you have customers demanding 15 loaves of bread, you make more profit on the last five because it doesn’t cost 50% more in material or labor to make 50% more loaves.

I have often used the example of making bread {Go Deep}. If you are making 10 loaves of bread, there is a set amount of cost associated with each loaf created. The total cost of each loaf is the total cost to produce the entire batch divided by ten. However, if you have customers demanding 15 loaves of bread, you make more profit on the last five because it doesn’t cost 50% more in material or labor to make 50% more loaves.

Your productivity in the last five loaves is higher because the fixed costs of production (raw materials, energy) barely change, and the labor is only slightly higher. The opposite is also true. It costs more per loaf to make fewer than ten loaves because the fixed costs and your labor are pretty consistent, yet the finished value of 7 loaves is less than the finished value of ten.

Anecdotally, it has looked for quite some time that around May of this year the economy peaked, plateaued for a few weeks, and then began a slow downward progression. Today the Bureau of Labor statistics puts some revised data to that third quarter (July, August and Sept) economic activity {data here}. The quantified results align with what we sensed was taking place.

The value of all products and services generated increased by 1.8 percent. However, the labor cost of generating that small amount of added value increased by 7.4 percent. The difference between those two numbers is a drop in productivity of 5.2% over the entire quarter.

This is the largest quarterly drop in productivity since 1960 !

The Biden administration will blame the drop in productivity on a lack of material to produce the end product (ie. the COVID excuse). Which means employed people were sitting around waiting for goods to arrive and being less productive. There is a small amount of that which might be true. However, it is not the biggest factor, at least not on this scale. Keep in mind we are talking about both goods and services.

The more likely cause of such a massive decline in productivity is a genuine decline in demand. In the aggregate, consumers needed less goods and services. This likelihood aligns with the diminished and softened retail sales figures recently noted. It is a simple cause and effect. When gasoline, energy, and essential products like food cost more, consumers have less money for other stuff. Demand for the non-essential products drop.

As the demand drops, the productivity of the economic activity to generate those goods and services also drops. However, the scale of the decline is the part to pay attention to. A five percent drop in productivity is huge for a single quarter. Under normal circumstances this means more slack in the labor market, and that is what we saw recently in the retail sector of the employment figures from November {data here}.

During the month when retailers are customarily ramping up their employment to cope with increases in consumer demand, last month that didn’t happen. The ‘retail sector‘ lost 20,000 jobs in November. Think about that.

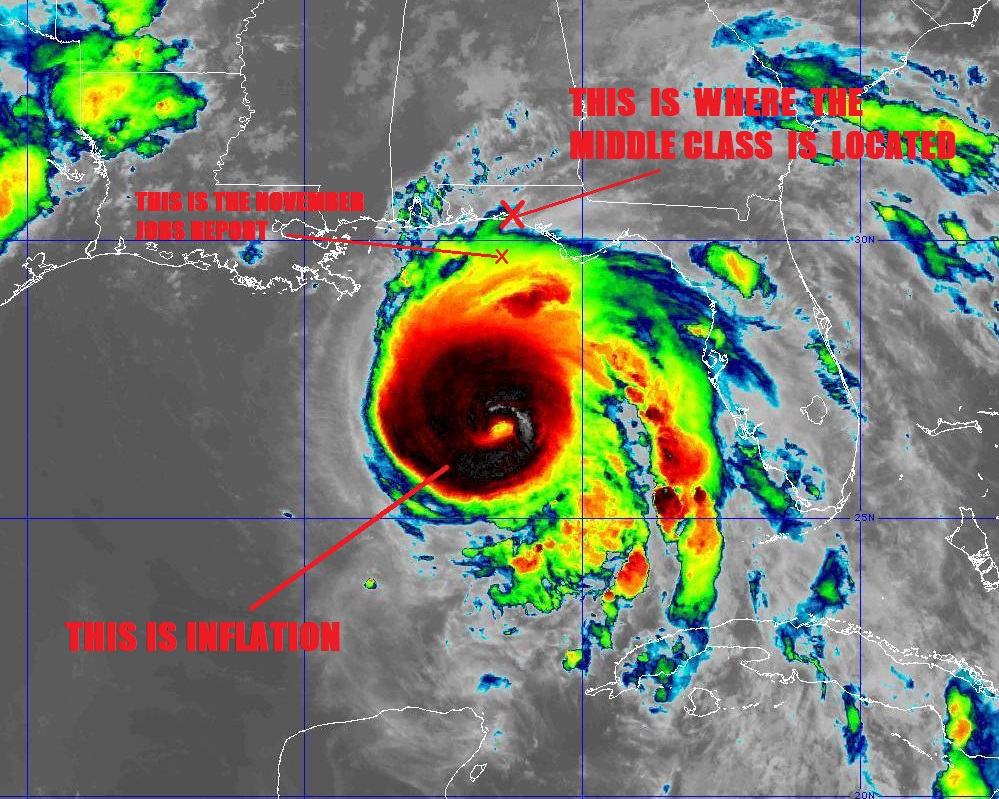

At the time of the November jobs report, the “national economists” were trying to figure out why the employment report missed expectations by 300,000+ jobs. We were not so surprised, because the actual result aligned with other data suggesting the Q3 economy overall was contracting. Consumers are being squeezed by inflation, that is creating a stagnant economy or “stagflation.”

Wage growth is currently at 3.9% {data}, and when combined with the loss in productivity, the unit labor costs for businesses at a macro level means a total cost of +9.6 percent in the third quarter. If employers do not start reducing their payroll costs as demand contracts, each unit produced will cost more money. Unfortunately, that dynamic adds to inflation and we grease the skids on this downward spiral.

I have not seen any financial pundits concerned about where this cycle naturally ends. Perhaps the media silence is because the White House knew the Q3 productivity data was alarming, and that stirred the administration to contact those pundits in advance in an effort to avoid widespread notice.

Regardless of reason for their avoidance, a drop in productivity of such a scale tells us to complete our economic preparations as soon as possible. The intensity of the inflation storm worsens with a weak employment outlook.