While the border crisis has become a major liability for President Biden, threatening his reelection chances, it’s become a huge boon to a group of nonprofits getting rich off government contracts.

Although the federally funded Unaccompanied Children Program is responsible for resettling unaccompanied migrant minors who enter the U.S., it delegates much of the task to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that run shelters in the border states of Texas, Arizona, and California.

And with the recent massive influx of unaccompanied children—a record 130,000 in 2022, the last year for which there are official stats—the coffers of these NGOs are swelling, along with the salaries of their CEOs.

“The amount of taxpayer money they are getting is obscene,” Charles Marino, former adviser to Janet Napolitano, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security under Obama, said of the NGOs. “We’re going to find that the waste, fraud, and abuse of taxpayer money will rival what we saw with the Covid federal money.”

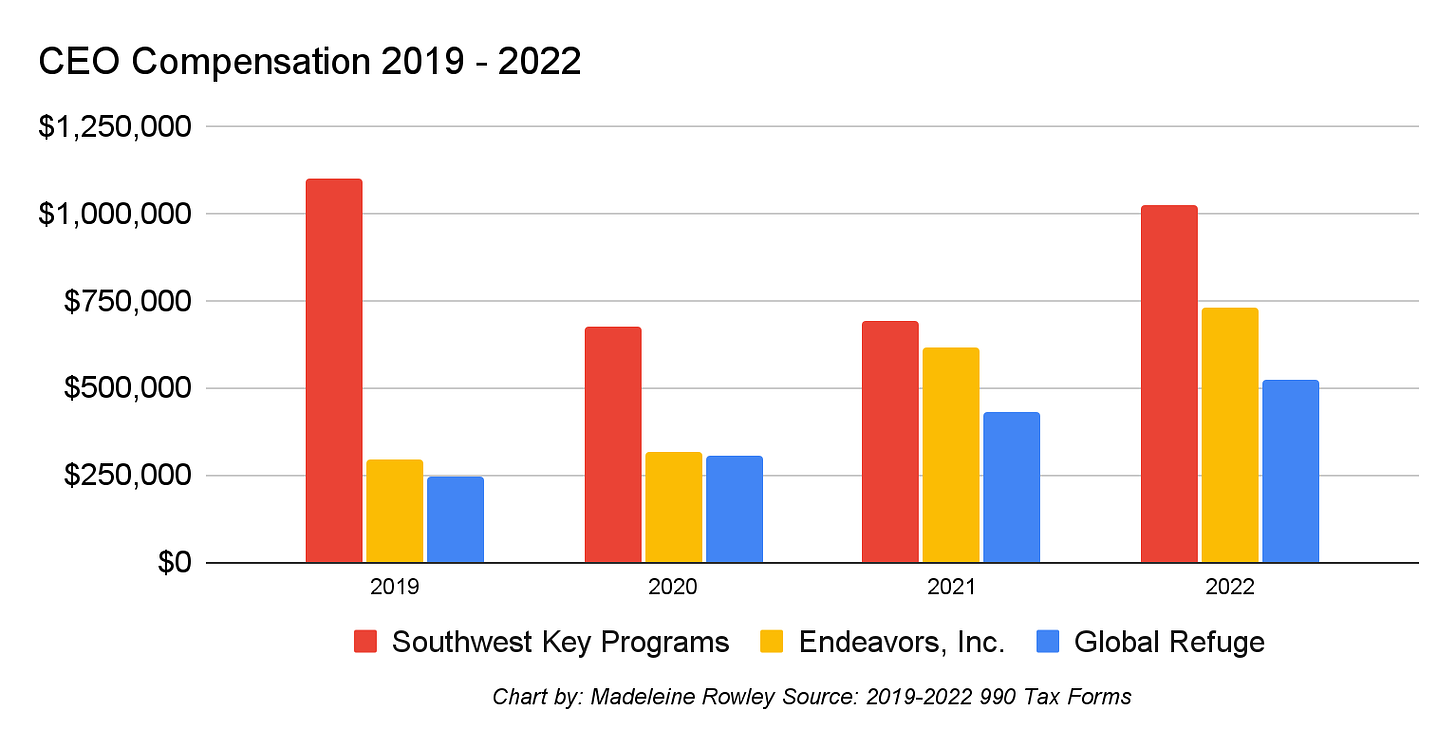

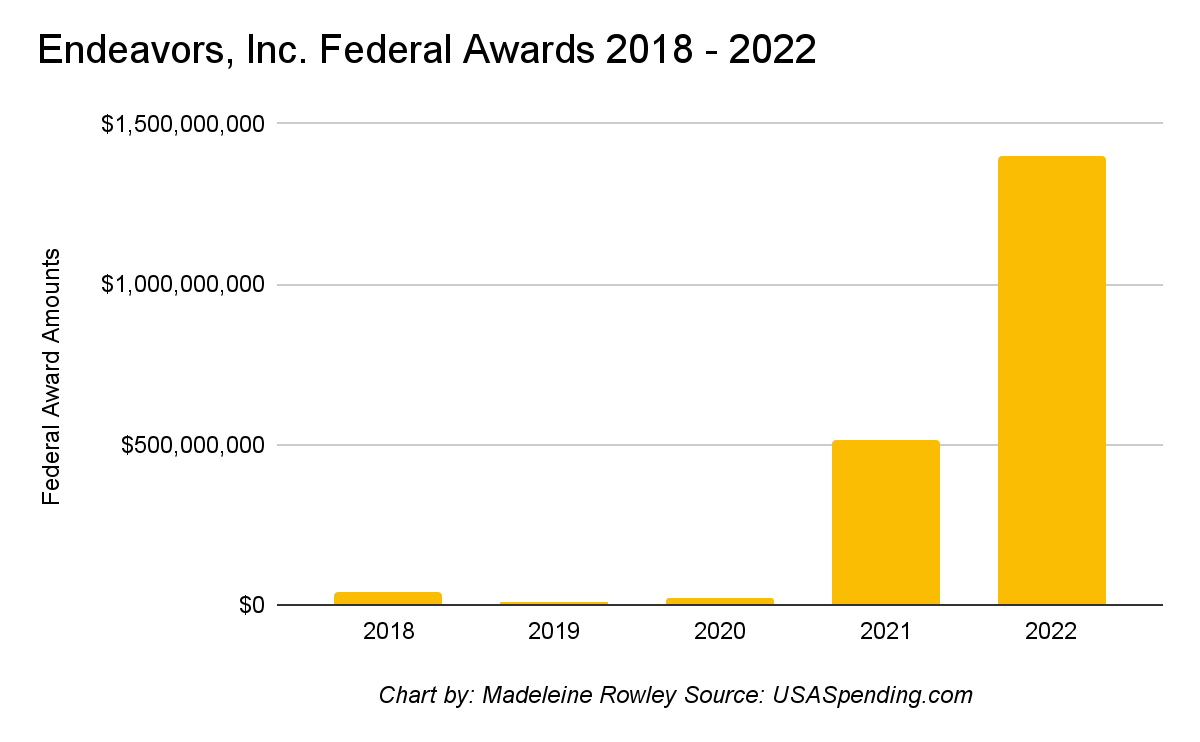

The Free Press examined three of the most prominent NGOs that have benefited: Global Refuge, Southwest Key Programs, and Endeavors, Inc. These organizations have seen their combined revenue grow from $597 million in 2019 to an astonishing $2 billion by 2022, the last year for which federal disclosure documents are available. And the CEOs of all three nonprofits reap more than $500,000 each in annual compensation, with one of them—the chief executive of Southwest Key—making more than $1 million.

Some of the services NGOs provide are eyebrow-raising. For example, Endeavors uses taxpayer funds to offer migrant children “pet therapy,” “horticulture therapy,” and music therapy.

In 2021 alone, Endeavors paid Christy Merrell, a music therapist, $533,000. An internal Endeavors PowerPoint obtained by America First Legal, an outfit founded by former Trump aide Stephen Miller, showed that the nonprofit conducted 1,656 “people-plant interactions” and 287 pet therapy sessions between April 2021 and March 2023.

Endeavors’ 2022 federal disclosure form also shows that it paid $5 million to a company to provide fill-in doctors and nurses, $4.6 million for “consulting services,” $1.4 million to attend conferences, and $700,000 on lobbyists. In 2021, the NGO shelled out $8 million to hotel management company Esperanto Developments to house migrants in their hotels.

Endeavors, which gets 99.6 percent of its revenue from the government according to federal disclosure forms, declined to comment to The Free Press.

The Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, funds the nonprofits through its Office of Refugee Resettlement, and its budget has swelled over the years—from $1.8 billion in 2018 to $6.3 billion in 2023. The ORR is expected to spend at least $7.3 billion this year—almost all of which will be funneled to NGOs and other contractors.

When asked about the funding increase during a January media event, Krish O’Mara Vignarajah, the chief executive of Global Refuge said, “We’ve grown because the need has grown.” The nonprofit did not make Vignarajah available for an interview.

But while it’s true the number of migrants has exploded in recent years, critics say these enormous federal grants far exceed the current need. The facilities themselves are generally owned by private companies and are leased to the NGOs, which house the unaccompanied minors and attempt to unite them with family members or, if that’s not possible, people who will take care of them—their so-called sponsors. The ORR does not publicly list the specific number of shelters it funds in its efforts to house migrants, a business The New York Times once described as “lucrative” and “secretive.”

While some NGOs have long had operations at the border, “what is new under Biden is the amount of taxpayer money being awarded, the lack of accountability for performance, and the lack of interest in solving the problem,” said Jessica Vaughan, director of policy studies at the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank that researches the effect of government immigration policies and describes its bias as “low-immigration, pro-immigrant.”

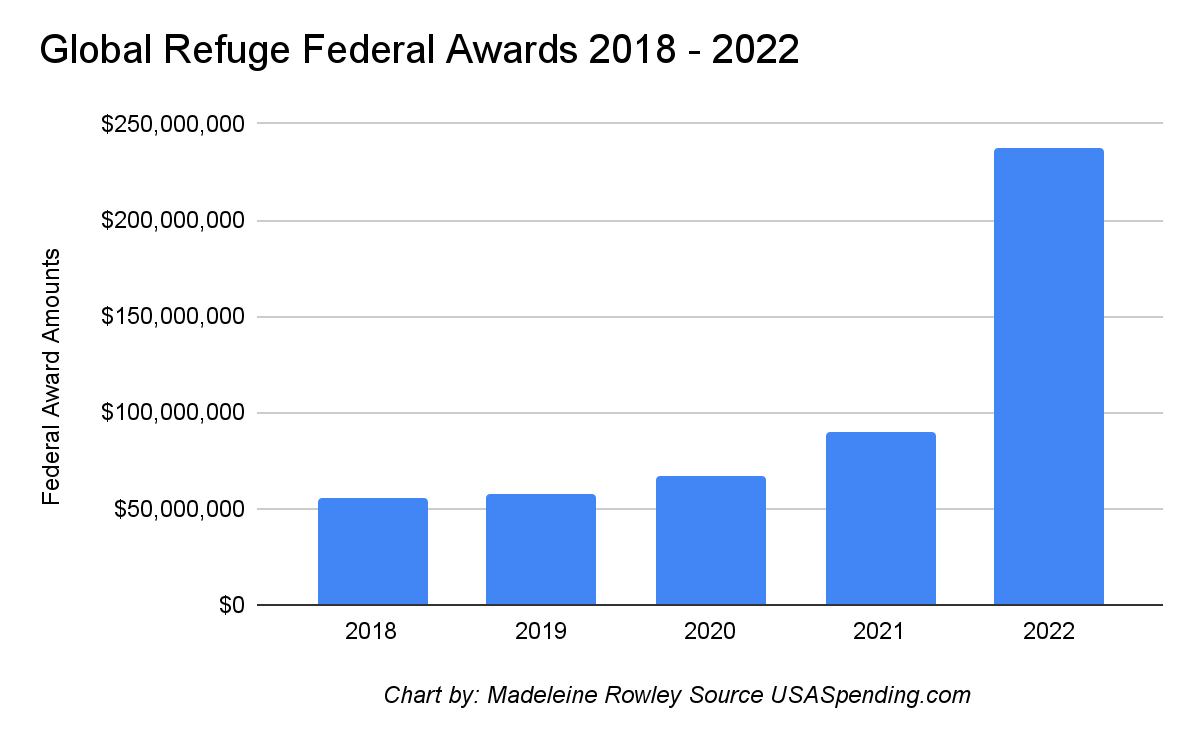

Consider Global Refuge, based in Baltimore, Maryland. In 2018, according to its federal disclosure form, the Baltimore-based nonprofit had $50 million in revenue. By 2022, its revenue totaled $207 million—$180 million of which came from the government. That year, $82 million was spent on housing unaccompanied children. Global Refuge also granted $45 million to an organization that facilitates adoptions as well as resettling migrant children.

Now Global Refuge employs over 550 people nationwide, and CEO Vignarajah said in January that the nonprofit plans to expand to at least 700 staffers by the end of 2024.

Vignarajah, a former policy director for Michelle Obama when she was first lady, took the top job at Global Refuge in February 2019 after she lost her bid to be elected governor of Maryland. She has since become one of the most prominent advocates for migrants crossing the southern border, appearing frequently on MSNBC and other media as an immigration advocate. Her incoming salary was $244,000, but just three years later, her compensation more than doubled to $520,000.

In 2019, Global Refuge housed 2,591 unaccompanied children while spending $30 million. Three years later, the NGO reported that it housed 1,443 unaccompanied children at a cost of $82.5 million—almost half the number of migrants for more than double the money.

In a statement to The Free Press, Global Refuge spokesperson Timothy Young said that while in care, “Unaccompanied children attend six hours of daily education and participate in recreational activities, both at the education site and within the community.”

The man with the $1 million salary is Dr. Anselmo Villarreal, who became CEO of Southwest Key Programs, headquartered in Austin, Texas, in 2021. (Villarreal took a drop in pay compared to his predecessor, Southwest Key founder Juan Sanchez, who paid himself an eye-popping $3.5 million in 2018.)

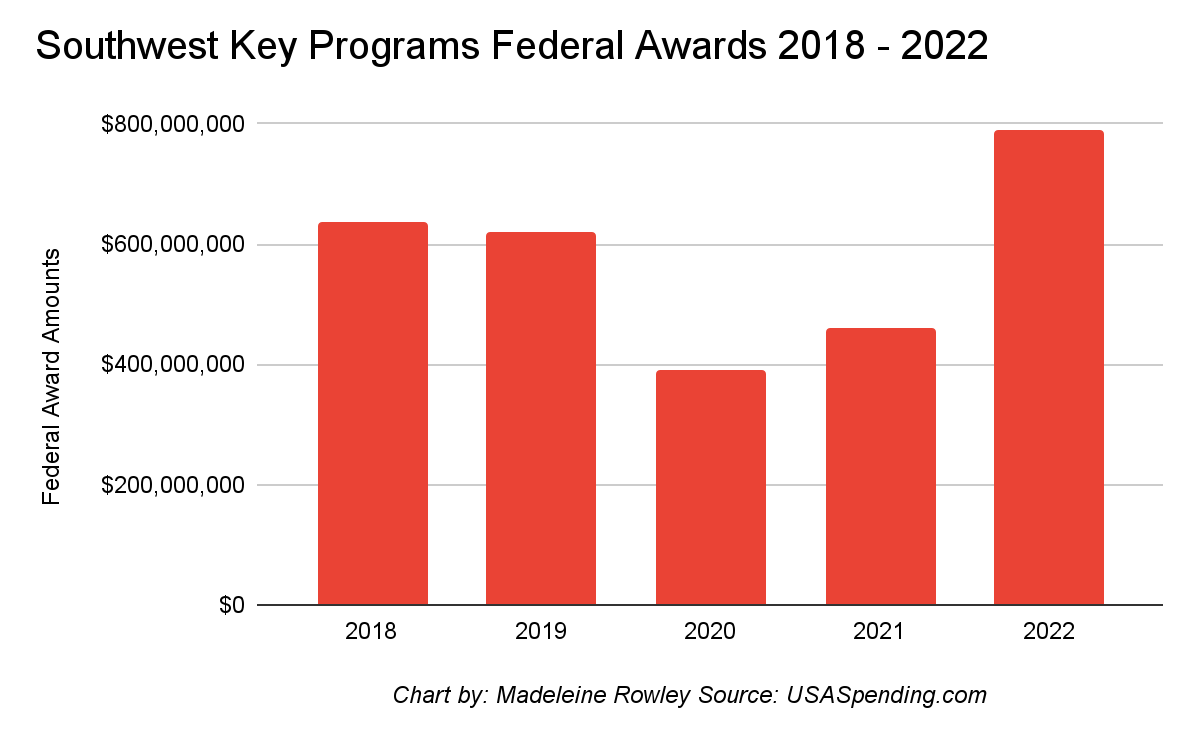

Despite a number of scandals in the recent past, including misuse of federal funds and several instances of employees sexually abusing some of the children in its care, Southwest Key continues to operate—and rake in big government checks. In 2020, the year of Covid-19, its government grant was $391 million; by 2022, its contract was nearly $790 million.

Southwest Key’s federal disclosure forms show that in 2022, six executives in addition to Villarreal made more than $400,000, including its chief strategist ($800,000), its head of operations ($700,000) and its top HR executive ($535,000). Its total payroll in 2022 was $465 million.

Endeavors, Inc., based in San Antonio, Texas, is run by Chip Fulghum. Formerly the chief financial officer of the Department of Homeland Security, he signed on as Endeavors’ chief operating officer in 2019 and was promoted to CEO this year.

In 2022, Fulghum was paid almost $600,000, while the compensation for Endeavors’ then-CEO, Jon Allman, was $700,000. Endeavors’ payroll went from $20 million in 2018 to a whopping $150 million in 2022, with seven other executives earning more than $300,000.

Perhaps the most shocking figure was the size of Endeavors’s 2022 contract with the government: a staggering $1.3 billion, by far the largest sum ever granted to an NGO working at the border. (In 2023, Endeavors’ government funds shrank to $324 million because the shelter was closed for six months. Endeavors says this was because the beds were not needed, the border crisis notwithstanding.)

Despite these astronomical sums, the Unaccompanied Children Program is fraught with problems and suffers from a general lack of oversight. Because so many unaccompanied youths are crossing the border, sources who worked at a temporary Emergency Intake Site in 2021 said the ORR pressured case managers to move children out within two weeks in order to prepare for the next wave of unaccompanied children.

In 2022, Florida governor Ron DeSantis empaneled a grand jury to conduct an investigation, which showed how the ORR continually loosened its safety protocols so children could be connected to sponsors more quickly—and with less due diligence.

The same report revealed that because there’s often no documentation to prove a migrant’s age at the time Border Patrol processes them, 105 adults were discovered posing as unaccompanied children in 2021. One of them, a 24-year-old Honduran male who said he was 17, was charged with murdering his sponsor in Jacksonville, Florida.

“We used to have DNA testing to make sure we had these family units,” Chris Clem, a recently retired Border Patrol officer, told The Free Press. But since the border crisis, the ORR has abandoned DNA testing, according to congressional testimony by the General Accountability Office. In 2021, ORR revised its rules so that public records checks for other adults living in a prospective sponsor’s home were no longer mandatory.

Tara Rodas, a government employee who was temporarily detailed to work at the California Pomona Fairplex Emergency Intake shelter in 2021, told The Free Press she also uncovered evidence of fraud within the sponsorship system. “Most of the sponsors have no legal presence in the U.S. I don’t know if I saw one U.S. ID,” said Rodas. “There were no criminal investigators at the site, and there was no access to see if sponsors had committed crimes in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico.”

Last October, the ORR published a series of proposed changes to its regulations in the Federal Register that will effectively codify the more relaxed standards. The new regulations, which will go into effect in July, will allow background checks and verifying the validity of a sponsor’s identity—but wouldn’t require them.

“It is mind-boggling that ORR has not seen fit to adjust the policies for (unaccompanied children) placements, except to make them more lenient,” Jessica Vaughan at the Center for Immigration Studies told The Free Press. “They could do a much better job, but they only want to streamline the process and make the releases even easier.” The Administration for Children and Families did not respond to emailed questions from The Free Press.

Deborah White, another federal employee temporarily detailed to the Pomona Fairplex facility in 2021, told The Free Press: “Ultimately, the responsibility is on the government. But the oversight is obviously not adequate—from the contracting to the care of the children to the vetting of the sponsors. All of it is inadequate. The government blames the contractor and the contractor blames the government, and no one is held accountable.”

Maddie Rowley is an investigative reporter. Follow her on X @Maddie_Rowley. And read Peter Savodnik’s piece, “A Report from the Southern Border: ‘We Want Biden to Win.’”