One thing you realize as you approach middle age is that even though your mind’s eye assures you that you’re still 25, mother nature has a vote, too. This includes everything from taking up CrossFit to throwing down in a bar fight. As the Good Book says, “The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.”

This parallels America’s participation in the Ukraine conflict, which is not quite going according to plan.

At first, the war looked like a good bet for the ruling party. Russia had long been an obstacle to their ambitions to remake the rest of the world in California’s image, and Republicans tend to rally around the flag in a foreign fight, forgetting that wars are run by the same federal government they’re hostile to in peacetime. The conflict also taps into latent anti-Russian feeling, a holdover from the Cold War, which many people don’t realize ended 30 years ago. Finally, the conflict is a good distraction from Joe Biden’s failures at home, and it looked like it would be easy. After all, we are the world’s “sole superpower,” right?

But the war is not really working out. Leaks confirm that Ukraine’s casualties have been horrendous, and that their vaunted spring offensive is unlikely to succeed. After the optimism and jingoism of the early days of the war—including nonsense like the “Ghost of Kyiv”—no serious person thinks Ukraine will win, even with the full might of NATO behind it. At best, the conflict will end in a draw. But even that doesn’t seem likely. If fighting somehow stopped today, Russia would end up with more than it started with, including a land bridge to Crimea at a minimum.

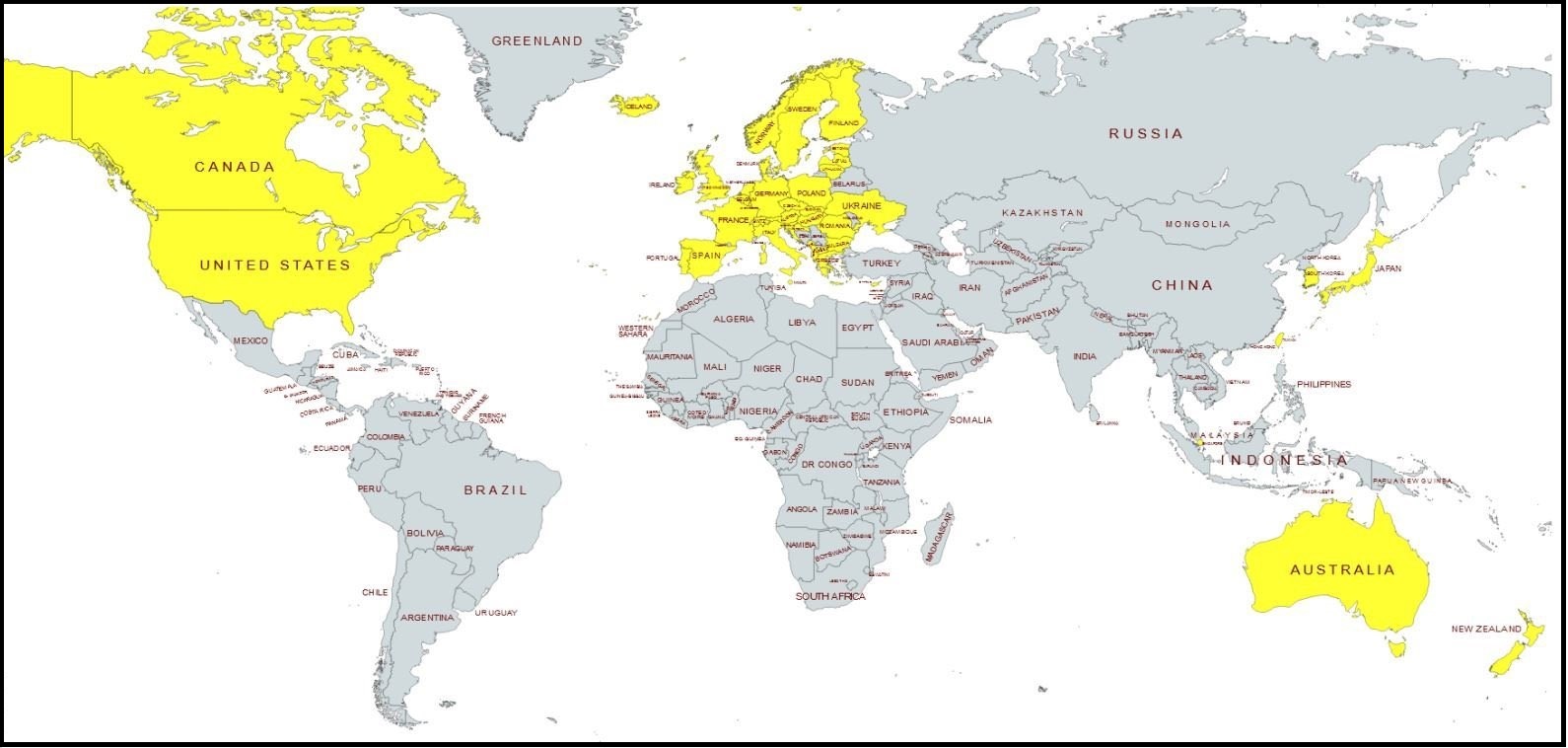

My guess is that Joe Biden and his team figured that the truly unprecedented economic sanctions on Russia would do most of the work, and that the rest of the world would cooperate in making these sanctions a success. Instead, Russia’s economy proved resilient, China maintained friendly neutrality, and everyone but Europe formed an anti-American bloc or professed neutrality, including the so-called BRICs. As the war has gone on, NATO members have divided over the war and its strategy.

Second Thoughts Leaking Out

There are starting to be some noises that the Western powers are going to abandon this enterprise, either cutting Ukraine loose or pushing it into some kind of armistice. Perhaps they always considered the operation a win-win, reasoning that it weakens Russia regardless of the outcome. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin let it slip in April 2022 that the whole purpose of our support was to weaken Russia.

This seems plausible and also profoundly foolish. Having put its prestige on the line and failing to achieve even NATO’s minimal stated objectives, Western assistance will discredit the United States and NATO in the case of a failure. This very public demonstration of Western powerlessness will be made worse if Russia dictates terms, expels Zelenskyy or tries him for war crimes, and forces Ukraine to relinquish its claims on Crimea and its Russophile East.

In a similar way, the Biden Administration’s pointless extension of the Afghanistan mission beyond the terms of Donald Trump’s negotiated agreement ended in a humiliating and chaotic withdrawal, which resulted in the abandonment of large amounts of military equipment and the shocking images of random Afghans making a mad dash for American cargo planes.

The Real Foundations of American Power

American power and prestige used to be rooted in two important qualities. The first was soft power. The United States had some credibility as an honest broker, eschewing the imperial ambitions of the European colonial powers and behaving magnanimously towards occupied Japan and Germany after World War II.

Thus, at least a fair number of Third World peoples were open to taking the American side in the Cold War. Even as recently as Grenada, Panama, and the First Gulf War, American forces departed after successful missions and did little to interfere with the governance or internal affairs of those who had invited them.

The second quality was our substantial economic power, which supported a military that was organizationally, technologically, and logistically superior to would-be rivals. From the end of the Cold War to at least 2010 or so, the United States had undisputed military dominance, which it dissipated through unsuccessful wars in the Middle East.

Now, having abandoned those enterprises, the United States and the military-industrial complex are looking for new dragons to slay, including Russia and China. But this is happening at a time when both components of American power—our reputation for justice and our combined economic and military power—are deeply compromised.

At the height of its military power, starting during the Clinton presidency, American leaders began to embrace an aggressive “idealism” that set out explicitly to change the character, values, and customs of the people in whose countries we intervened. Purely “humanitarian” interventions like Kosovo became common.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, this idealism meant feminism and democracy. In Eastern Europe, it meant the promotion of gay rights and secularism, alienating the people who previously associated America with prosperity, blue jeans, and support for religious freedom during the Cold War.

The frequent American invocation of “freedom” and “democracy” started to sound like a threat or, at the very least, disrespect to people whose priorities, existing elites, and values were out of step with those of the West’s ruling classes.

Our leaders have also demonstrated a discrediting Machiavellianism in recent years. While this was probably always present in some measure, it is now completely unrestrained and unapologetic. It becomes discrediting in light of all the pious talk of the “rules-based international order.”

Bombing the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which was designed to fuel German industry, showed that being allied with the United States could prove nearly as dangerous as being an opponent. Respect for the sovereignty of other nations, including their right to govern their internal and foreign affairs, cannot be squared with the current American understanding of being the “sole superpower.”

While we have abandoned the relatively cheap soft-power approach of yesteryear, the long-festering problems with procurement and the defense industrial sector are now exposed in ways that the low-tech insurgencies of Iraq and Afghanistan masked. We cannot supply Ukraine with the number of missiles and artillery shells it needs. We cannot repurpose other facilities for these projects. And we cannot field new weapon systems at the pace required to keep up with China and Russia. We are not in our prime anymore, either in absolute or relative terms.

Wisdom and Restraint

A sensible nation—like a sensible man of middle age—has acquired some wisdom to compensate for its limits and can adjust its ambitions to match its abilities. If the youthful America of the 20th century was foolhardy, brash, and full of energy, it was also sometimes naïve and short-sighted, lacking the perspective of more established powers.

As with people, not every nation learns the lessons of experience. We all know those who are repeatedly getting with the wrong kinds of romantic partners or spending beyond their means to the point of disaster.

Recent follies suggest that the members of the American ruling class, including the foreign policy “blob,” are trapped by their unwisdom. They cannot accept reality, lack the appropriate education to understand other nations’ perspectives, and cannot develop a strategy that advances our objective national interests in an economical way.

Their failures are made worse by the failure of the political branches, the media, and voters to impose discipline on our foreign policy. Foreign policy has become an elite plaything, ignored by voters until it does something particularly offensive or that results in tangible harm at home, such as the OPEC embargoes of the 1970s or the 9/11 attacks.

With the burdens of war borne by an all-volunteer military, and the United States protected by two oceans, as well as its nuclear arsenal, the costs of American foreign policy failures are more modest than they would be for a nation like, say, Poland. Huge starting advantages and a low-accountability culture have encouraged persistent mediocrity and poor decision-making.

Just like the middle-aged man trying to relive his glory days, America has been trying to recapture the moral high ground and sense of triumph from its World War II victory. But the world is a different place. Similar to 1945, we must deal with rising powers, as well as legacy ones, that feel strongly about their right to a place in the sun. But, unlike in 1945, we are no longer the supremely productive, innovative, culturally united, and powerful America of yesteryear.

Lacking infinite power and infinite advantages, we must instead be strategic, directing limited resources to accomplish the minimum requirements of any foreign policy: our domestic security and prosperity. Unfortunately, now this strategy must also account for the additional burdens arising from our expensive involvement in the doomed Ukraine campaign.