A Georgia county prosecutor is making the Jan. 6 show trial look like a paragon of propriety and due process. But now the targets of Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis’s political hit job are beginning to push back in the courts against her outrageous abuse of the criminal justice system.

In January 2022, Willis requested that the chief judge of the Fulton County Superior Court, Christopher Brasher, impanel a “special grand jury” to assist in her supposed investigation “into any coordinated attempts to unlawfully alter the outcome of the 2020 elections in this state.” Willis’s request, however, made clear that the “special grand jury” would not be used to indict anyone but to issue a report at the conclusion of its supposed investigation, making “recommendations concerning criminal prosecution as it shall see fit.”

The fact that Willis’s special grand jury lacks the power to return criminal indictments provided the initial proof that Willis seeks both self-promotion and to damage her political opponents, not to prosecute purported lawbreakers. Willis then confirmed her dual fame-seeking and political-warfare goals earlier this month when, as part of Fulton County’s purported investigation into “criminal disruptions” of Georgia’s administration of the 2020 general election, she obtained court approval to subpoena some big names. These included Trump’s election lawyers such as Rudy Giuliani, John Eastman, Jenna Ellis, Cleta Mitchell, and Kenneth Chesebro, as well as Sen. Lindsey Graham and attorney and podcast host Jacki Pick Deason.

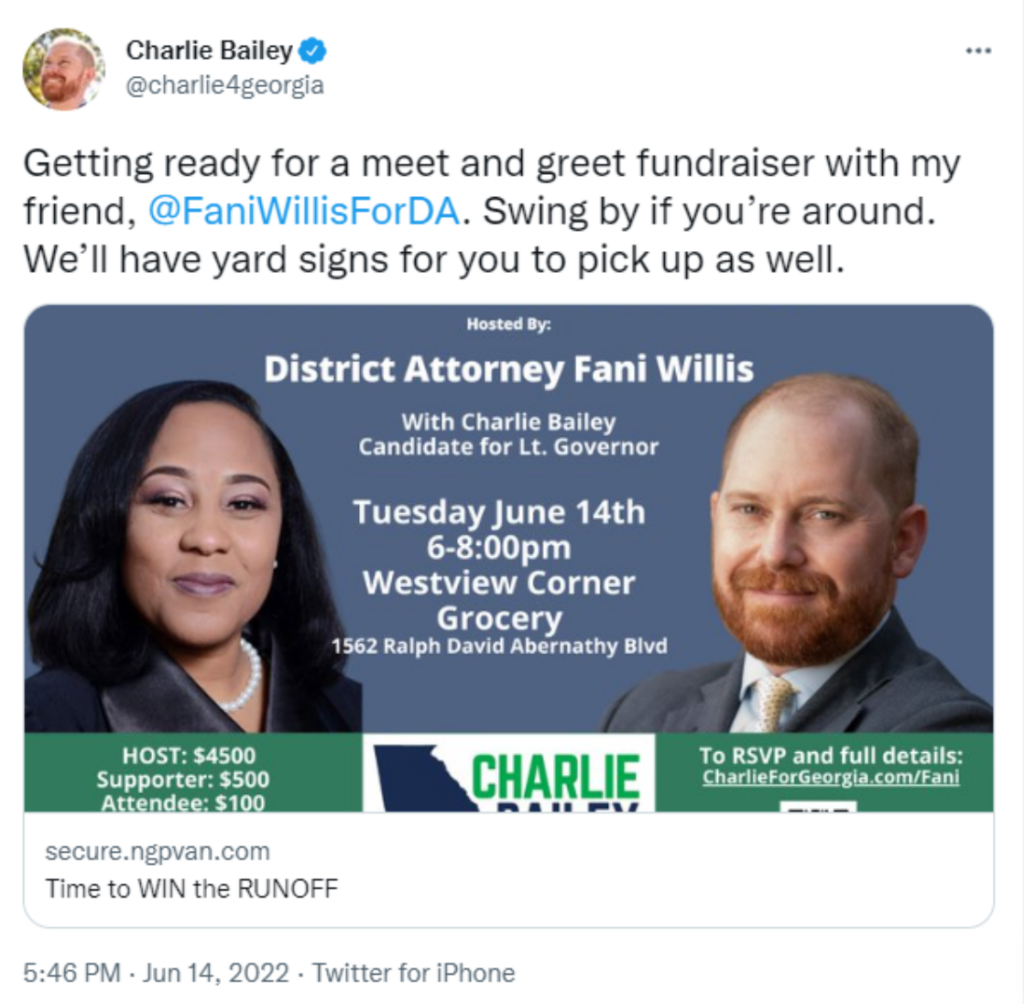

Willis’s use of the special grand jury to subpoena several of Trump’s attorneys serves no purpose but to push a “political farce because attorney-client privilege will prevent Trump’s lawyers from answering many of the questions likely to be posed.” The county prosecutor’s reported targeting of some of the top Georgia Republicans, including the GOP’s current candidate for lieutenant governor — who will face off this fall against Democrat Charlie Bailey — likewise screams of a political witch hunt, for Willis just happens to be a strong supporter of Bailey, having donated $2,500 to his campaign and having hosted a fundraiser for the Democrat candidate last month.

But it is the local prosecutor’s decision to target Graham that represents the apex of Willis’s absurdity because the Speech or Debate Clause of the Constitution protects our U.S. senators and representatives from such local political crusades.

Look to the ‘Speech or Debate Clause’

Article I, Section 6 of the Constitution provides that “for any Speech or Debate in either House, [members] shall not be questioned in any other Place.” This clause, known commonly as the “Speech or Debate Clause,” applies not merely to “speech” and “debate” in the literal sense, but to all “legislative acts.”

Over the years, the courts have further explained the scope of the Speech or Debate Clause, stressing that it must be applied “broadly” to achieve its purpose, and “protects a member’s conduct if it is an integral part of the due functioning of the legislative process.” Thus, the clause protects acts by which members deliberate and communicate “with respect to the consideration and passage or rejection of proposed legislation or with respect to other matters which the Constitution places within the jurisdiction of either House.”

Notwithstanding the breadth of the Speech or Debate Clause, a county prosecutor in Georgia demands that the South Carolina senator travel to the Peach State to be questioned before a grand jury about two telephone conversations he allegedly had with state officials after the November 2020 election. While Willis seeks to portray Graham’s calls to state officials as somehow nefarious, a senator questioning the secretary of state on reported irregularities in Georgia’s election falls squarely within the “matters” the Constitution places within the jurisdiction of Congress.

Specifically, Congress, which has “all Legislative powers” under our federal Constitution, passed the Electoral Count Act, which authorizes federal lawmakers to raise objections to the states’ certificates of electors. Further, under the Electoral Count Act, members of both chambers must then “decide upon an objection that may have been made to the counting of any electoral vote or votes from any State.” First, though, under this law, members of Congress may “speak to such objection or question” for five minutes.

Graham did precisely that on January 6, 2021, when in response to objections to the electors of various states, he rose to the Senate floor and explained his rationale for rejecting the objections. Graham’s floor speech made clear he had inquired about both claims of illegal voting and fraud. “Georgia: They say the secretary of state took law into his own hands, he changed the elections laws unlawfully,” Graham noted. But “a federal judge said ‘no.’ I accept the federal judge even though I don’t agree with it,” he continued. “Fraud: They say there’s 66,000 people in Georgia under 18, voted,” the South Carolina senator added. “I asked, ‘give me 10,’” but he “got one.” Graham then proceeded to vote to certify the election.

Clearly, Graham’s statements from the floor of Congress are protected by the Speech or Debate Clause. But again, the protections afforded by that clause are not so limited as to apply only to words spoken from the seat of the Capitol. Rather, the Supreme Court has noted that while not everything “in any way related to the legislative process” is protected by the clause, legislators’ preparations for the “legislate process” are protected.

While case law interpreting the clause provides little to no guidance on what constitutes such “preparations,” last term the U.S. Supreme Court — in Trump v. Mazars USA, in discussing whether Congress has the power to issue certain subpoenas — elaborated on the “legislative function.”

“Without information,” the court explained, “Congress would be shooting in the dark, unable to legislate ‘wisely or effectively.’” Accordingly, “congressional power to obtain information is ‘broad’ and ‘indispensable,’” and “it encompasses inquiries into the administration of existing laws, studies of proposed laws and ‘surveys of defects in our social, economic, or political system for the purpose of enabling the Congress to remedy them.’”

The Mazars opinion thus makes clear that obtaining information for the purpose of legislating “wisely or effectively” constitutes an appropriate “legislative function.” And the Supreme Court has held that “when the Speech or Debate Clause is raised in defense to a subpoena, the only question to resolve is whether the matters about which testimony are sought ‘fall within the “sphere of legitimate legislative activity.”’” If so, that clause serves as an “absolute bar to interference.”

Reading the Mazars analysis, then, in light of case law interpreting the Speech or Debate Clause, strongly supports the conclusion that a state prosecutor cannot force the South Carolina senator to appear in Georgia to be questioned about his conversations with Georgia officials regarding the 2020 election. That holds true no matter how Willis frames Graham’s motive because the Supreme Court precludes any inquiry into the motivations for acts that occur in the regular course of the legislative process.

Founders Tried to Prevent Bad Actors Like Willis

Beyond the plain language of the Speech or Debate Clause, the original intent of that constitutional provision confirms that the founding generation, in ratifying the Constitution, sought to prevent precisely the shenanigans Willis is playing.

The Founding Fathers included the Speech or Debate Clause in the federal Constitution, the Supreme Court explained, “to protect the integrity of the legislative process by insuring the independence of individual legislators.” “The central object of the Speech or Debate Clause is to protect the ‘independence and integrity of the legislature,’” the high court explained, and to prevent “intimidation of legislators by the Executive and accountability before a possible hostile judiciary.” Further, the “rights of the people,” the authors of our Constitution believed, would be best protected if the representatives could “executive the functions of their office without fear” of interference.

Now, some 230 years later, a partisan Democrat D.A. in Georgia is proving the prescience of the framers, with her targeting both Graham and Republican Rep. Jody Hice with subpoenas approved by a local judge, who is arguably hostile to the Republican representatives: The chief judge of the Fulton County Superior Court, Christopher Brasher, who both impaneled Willis’s “special grand jury” and approved her requests for subpoenas, is the same county judge who delayed appointing a judge to hear Trump’s Georgia election challenges until it was too late to matter.

Both Graham and Hice seek to sidestep the state court sideshow by removing the cases to federal court and obtaining orders quashing the subpoenas. Graham had also filed a motion in a South Carolina federal court last week and obtained an initial order staying Willis’s efforts to question him pending further proceedings. However, Graham later agreed to dismiss that case and refile his challenge to a grand jury subpoena in a federal court in Georgia, which he is expected to do sometime early next week.

Hice has already filed his motion to quash the subpoena in a Georgia federal court, and a hearing is scheduled before Judge Leigh Martin May, a Barack Obama appointee, on Monday at 2:00 p.m.

While Monday’s hearing on Hice’s motion will provide a first read on how the courts will apply the Speech or Debate Clause in the context of Willis’s grand jury probe, no matter how she rules, Judge Martin May’s decision will likely be appealed to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals by the losing party. Further, even pending that appeal, Martin May’s decision in Hice’s case will not dictate the outcome in Graham’s forthcoming case for two main reasons.

First, as a district court judge, rulings by Martin May do not bind other federal judges. Thus, if Graham draws a different federal judge in the northern district of Georgia, that judge may disagree with Martin May’s ruling. Second, Hice’s case differs from Graham’s case in that Hice attempts to block questioning on “any discussions” he “may have had with individuals or organizations that had information on, or an interest in investigating, alleged irregularities in the election,” while Graham seeks protection from questioning about two alleged conversations with Georgia state officials — which is the only purpose for which Willis claimed Graham was an indispensable witness.

In ruling on Hice’s motion, the court may be more inclined to rule that certain categories of questions are off limits, as opposed to all questioning, whereas with Graham, since Willis seeks only to question Graham about his conversation with Georgia state officials, all questioning should be off limits. Courts have taken both tacks in prior Speech or Debate cases, either precluding all questioning or limiting questioning to certain categories.

But in this case, a court would also be justified in telling Willis to wait until she has a real grand jury — one that can indict — because anything less establishes that her interest is political and seeks solely to “intimidate” the legislators. And that is precisely what the Speech or Debate Clause seeks to prevent.