It’s been six weeks since Russia invaded Ukraine, aiming to topple the government in Kyiv in a lightning strike. But contrary to much of Western and Russian intelligence, the Ukrainians refused to be cowed. They fought back adroitly, exploiting Russian weaknesses in training, morale, logistics, maintenance, and command and control. And now the war is entering an entirely new phase, one that may grow more dangerous for Ukraine with time.

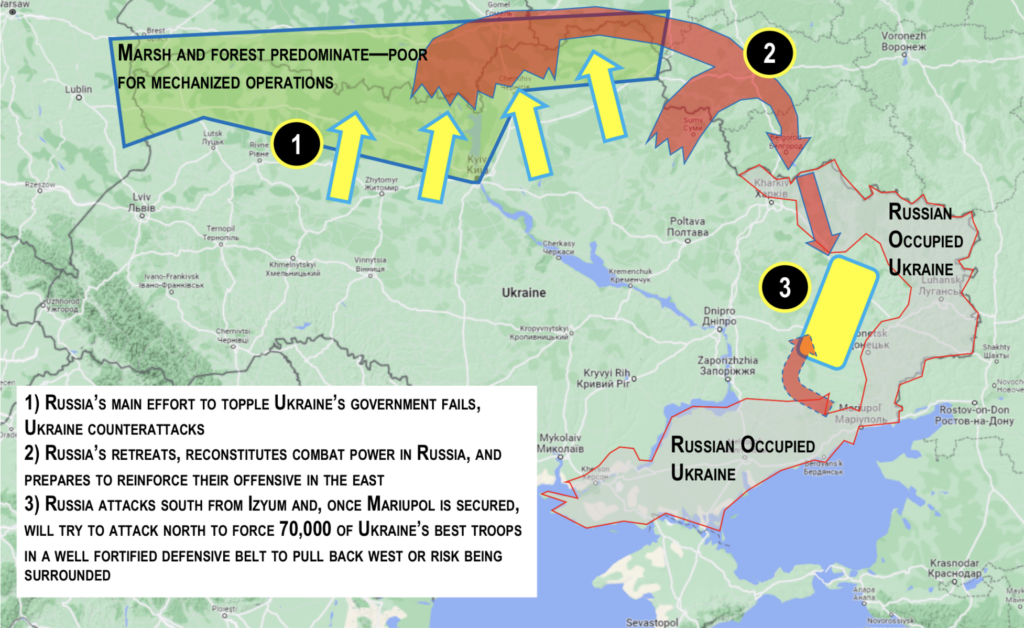

Military intelligence officers are taught to look at the terrain, weather, and the enemy threat. Ukraine’s border with Belarus and the westernmost portion of the Russian border is replete with marshes, rivers, and forests. In the best of weather, it’s not ideal for mechanized operations — tanks, other tracked vehicles, and trucks. During a mild winter with no hard freeze, with the Ukrainians having preemptively flooded much of the terrain, it’s even worse.

This is where the Russian main effort stalled. It could not be adequately resupplied, likely due to both Ukrainian efforts, the poor road network, and bad cross-country mobility. That Russia tried to attack through this area shows one or both of two things: utter contempt for Ukraine’s military capacity (likely a view Russia no longer holds), and a failure to conduct the most basic intelligence preparation of the battlefield.

Russia Moving East

Russia’s defeated forces in the vicinity of Kyiv have now mostly retreated or been pushed out of Ukraine by steady Ukrainian counterattacks. These forces are moving to the east, likely in the vicinity of the Russian cities of Kursk and Belgorod, to refit, take on replacements, and undergo training before being assigned to Russia’s renewed offensive effort in the eastern Donbas Basin region.

Unlike the terrain north of Kyiv, this area features mostly open terrain except along the Siverskyi Donets River running roughly east-southeast from Izyum — recently captured by the Russians — to Lysychansk, which remains under Ukrainian control. And while the ground is still soft, it is still more amenable to cross-country movement, playing into the three main Russian strengths: artillery, tanks, and air support.

The next phase of Russia’s offensive will likely be aimed at dislodging the 70,000 well-equipped Ukrainians who have been fighting the Russian-officered separatist forces in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions since 2014. These 70,000 troops represent about one-third of Ukraine’s active-duty army. They benefit from high morale, excellent training, and extensive fortifications that allow them to readily block Russian penetrations. But fortifications are fixed, and if the Russians can get behind them, the Ukrainians will have to pull back to the west or risk being surrounded.

Putin’s Best Chance for Victory

Further complicating the situation in the east is the brutal siege of Mariupol, along the coast of the Sea of Azov. If Russia finally secures the city, it may be able to mount an assault from the south, presenting Ukraine’s defenders with a double envelopment. Or it may be that the Russian forces reducing Mariupol to rubble will themselves be spent — achieving a pyrrhic victory that can add little to follow on success directly north.

If Russian President Vladimir Putin’s army can adjust and overcome or compensate for its weaknesses, this will be the place and the battle that offers Putin his best chance for victory.

This new fight puts a premium on tanks and airpower — both areas of Russian superiority. This makes the Czech Republic’s provisioning of about a dozen Soviet-era T-72 tanks to Ukraine all the more important.

Additionally, both the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic have provided other tracked vehicles, artillery, and ammunition to Ukraine. Both nations are also said to be preparing to lend their military repair capabilities to restore battle-damaged Ukrainian and captured Russian equipment back to fighting shape. Ukraine has captured some 500 tanks and other tracked vehicles.

Ukraine will need all that assistance and more, if it hopes to withstand overwhelming Russian firepower. That the Czechs — where Russian agents were blamed for destroying some 150 tons of Soviet-era ammunition in 2014 — and Slovaks have provided Ukraine with armor shows that much more can be done short of sending NATO troops to Ukraine, the one action that is certainly a red line that Putin will not tolerate without a response.