When Russian President Vladimir Putin greenlighted the invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, he expected a quick collapse of the Ukrainian government. Had Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy fled, Putin might have seen the installation of a pro-Moscow puppet regime that would have greatly lessened the need for Russian occupation forces. It didn’t happen as planned.

Now, some 180,000 Russian troops of the initial force of 200,000 are estimated to have been committed to the invasion. This force is pressing in on a nation of 46 million people with a territory almost as large as Texas.

Ukraine’s active military at the onset of the war was 200,000. Their reserve forces are reported to be as high as 900,000 with another 7 million people who are fit for military duty.

With Putin’s political objective of installing a friendly government in Kyiv out of reach, the Russians now seem intent on increasing the cost of resistance to Ukraine, depriving the nation of electricity and water while driving millions of refugees into Europe.

Comparing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine from the north, east, and south, with the German-led invasion from the west and southwest in 1941 yields some interesting comparisons.

In 1941, the German Army Group South had about 941,000 soldiers and 1,000 tanks. The Romanian military, with a German army attached, mustered about 640,000 men and 250 tanks from the southwest. Hungarians contributed another 30,000 in the early stages of the invasion. Facing the Axis onslaught. Thus, about 1.6 million men were committed to the operation — about eight times larger than the force Russia has committed so far.

Facing them were two Red Army groupings (called fronts) totaling slightly more than 1 million men with almost 5,700 tanks.

The Germans invaded on June 22, 1941. By Aug. 23, two months later, the battle of Kiev had started and by Sept. 26, the Soviet defenders having been surrounded, the city was taken. The distance to Kyiv from the German jumping-off points in occupied Poland was almost double the distance of the Russian staging areas in Russia northeast of Kyiv.

Also of note, the Axis began its siege of Odessa on Aug. 8. The mostly Romanian-led effort to reduce the city lasted for about 10 weeks until Oct. 16. Unlike today for Ukraine, however, the Soviet Union had a modest ability to resupply the port city by the Black Sea.

Importantly, under Stalin, Ukrainians were largely disarmed. Anti-Axis partisans eventually numbered more than 250,000 in Ukraine, but these formations had to be armed and supplied by Soviet efforts (though some were soldiers caught up in 1941’s massive pockets who escaped into the woods and marshes rather than surrender).

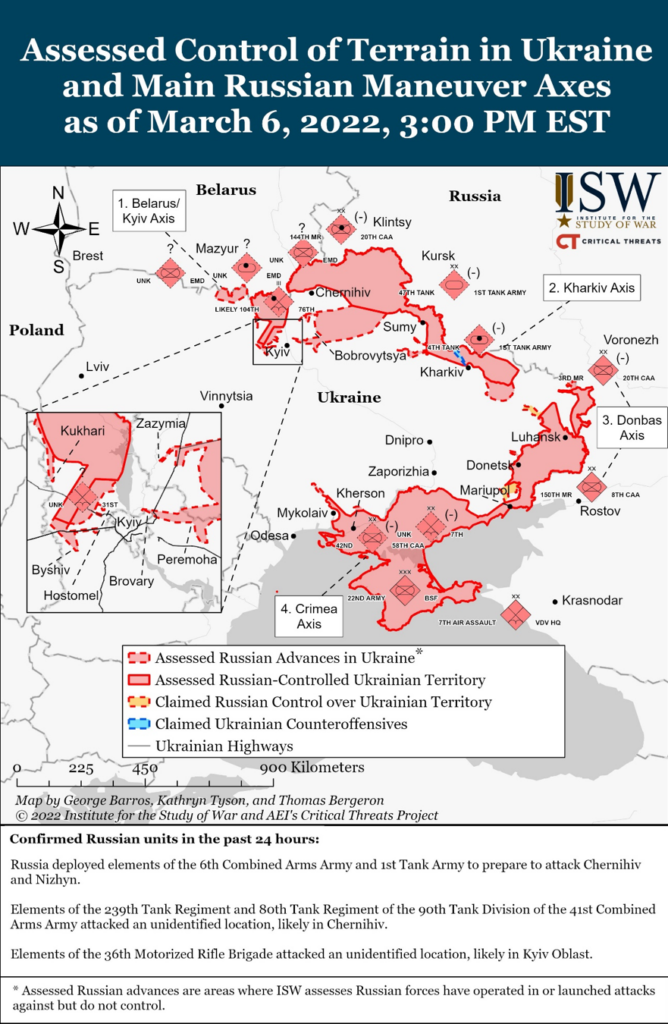

While modern weaponry, sensors, and communications allow for different tactics, the basic math of an occupation stands—soldiers on the ground are required to occupy a region. With insufficient soldiers, the terrain is only temporarily held. As analysts pour through open-source information to try to understand the largest conflict Europe has seen since the end of WW2, there have been numerous products produced to illustrate what’s happening. One of the better ones is a daily update from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW).

The analysts at ISW distinguish between areas they assess as “Russian controlled” vs. those areas that Russian forces have merely advanced through. Even so, this approach can be misleading.

Nathan Ruser with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute has produced a completely different set of maps that, in many ways, is far more revealing.

Mr. Ruser has traced the routes Russian battalion tactical groups have taken as they attempt to impose Moscow’s will on Kyiv. Ruser’s map shows a series of highways and secondary roads over which the Russians must maintain supply lines, provide local security from Ukrainian attacks, and maintain a basic level of anti-aircraft capacity.

There are three additional points to consider in comparing Ruser’s map with the more conventional ISW map.

First, the Russian mud season — Rasputitsa (no relation to Rasputin) — usually runs a month or two in the fall and in the spring. There was no hard freeze in Ukraine this year, so Rasputitsa never ended. This means that vehicles leaving a hardball road risk becoming mired and photos from the conflict suggest many have.

Second, the areas north of Kyiv, to the west and east of the Dnieper River, are very marshy. This further restricts off-road movement. Complicating this matter for the Russian invaders is the reported intentional flooding of the low-lying areas north of Kyiv. This action mirrors measures taken by the Dutch to slow the German attack in 1940 — measures the Germans took themselves in 1944-45.

Third, modern armies are far more road-bound than armies of the past. Few Russian soldiers dismount from their vehicles until in actual combat. As a result, significant portions of the Ukrainian countryside have yet to be pacified by the Russians.

Thus, in addition to the Russian force being of insufficient size to occupy Ukraine, the way it has been deployed and is being resupplied opens up a major vulnerability: its forces are stretched out along roads and not able to provide mutual support. The Ukrainians reportedly took advantage this of over the weekend when a sortie out of Kharkiv ambushed Russian forces northwest of the city (Shown as the thin blue line on the ISW map).

Lastly, one other important development to consider.

Sometime on Friday, a Ukrainian military cargo aircraft was seen flying to an airport just outside of Istanbul, Turkey. The location of the airport was close to Baykar, the Turkish firm that designed and builds the Bayraktar TB2, an armed drone used to great effect by the Ukrainians in the opening days of the conflict. The aircraft returned to a Polish airfield near Lviv. In all likelihood, this aircraft was filled with Bayraktar TB2 and control stations. Days earlier, it was reported that several Turkish Air Force cargo flights were made between Ankara and Rzesow in southern Poland. Concurrently, Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov announced that a shipment of new Turkish combat drones were pressed into service.

Look for the replenished stock of Bayraktar TB2s to begin targeting Russian surface-to-air missile systems thus allowing the remaining Ukrainian air force to begin attacking Russian columns of armor and supply trucks with a reduced likelihood of being shot down.