Article by Eric Levitz for the New York "Intelligencer":

In

September 2006, Nouriel Roubini told the International Monetary Fund

what it didn’t want to hear. Standing before an audience of economists

at the organization’s headquarters, the New York University professor warned

that the U.S. housing market would soon collapse — and, quite possibly,

bring the global financial system down with it. Real-estate values had

been propped up by unsustainably shady lending practices, Roubini

explained. Once those prices came back to earth, millions of underwater

homeowners would default on their mortgages, trillions of dollars worth

of mortgage-backed securities would unravel, and hedge funds, investment

banks, and lenders like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could sink into

insolvency.

At

the time, the global economy had just recorded its fastest half-decade

of growth in 30 years. And Nouriel Roubini was just some obscure

academic. Thus, in the IMF’s cozy confines, his remarks roused less

alarm over America’s housing bubble than concern for the professor’s

psychological well-being.

Of

course, the ensuing two years turned Roubini’s prophecy into history,

and the little-known scholar of emerging markets into a Wall Street

celebrity.

A decade later, “Dr. Doom” is a bear once again. While many investors bet on a “V-shaped recovery,” Roubini is staking his reputation on an L-shaped depression. The economist (and host of a biweekly economic news broadcast) does

expect things to get better before they get worse: He foresees a slow,

lackluster (i.e., “U-shaped”) economic rebound in the pandemic’s

immediate aftermath. But he insists that this recovery will quickly

collapse beneath the weight of the global economy’s accumulated debts. Specifically, Roubini argues that the massive private debts accrued

during both the 2008 crash and COVID-19 crisis will durably depress

consumption and weaken the short-lived recovery. Meanwhile, the aging of

populations across the West will further undermine growth while

increasing the fiscal burdens of states already saddled with hazardous

debt loads. Although deficit spending is necessary in the present

crisis, and will appear benign at the onset of recovery, it is laying

the kindling for an inflationary conflagration by mid-decade. As the

deepening geopolitical rift between the United States and China triggers

a wave of deglobalization, negative supply shocks akin those of the

1970s are going to raise the cost of real resources, even as

hyperexploited workers suffer perpetual wage and benefit declines.

Prices will rise, but growth will peter out, since ordinary people will

be forced to pare back their consumption more and more. Stagflation will

beget depression. And through it all, humanity will be beset by

unnatural disasters, from extreme weather events wrought by man-made

climate change to pandemics induced by our disruption of natural

ecosystems.

Roubini allows that, after a decade of misery, we may get around to developing a

“more inclusive, cooperative, and stable international order.” But, he

hastens to add, “any happy ending assumes that we find a way to survive”

the hard times to come.

Intelligencer recently spoke with Roubini about our impending doom.

You

predict that the coronavirus recession will be followed by a lackluster

recovery and global depression. The financial markets ostensibly see a much brighter future. What are they missing and why?

Well, first of all, my prediction is not for 2020. It’s a prediction that these ten major forces

will, by the middle of the coming decade, lead us into a “Greater

Depression.” Markets, of course, have a shorter horizon. In the short

run, I expect a U-shaped recovery while the markets seem to be pricing

in a V-shape recovery.

Of

course the markets are going higher because there’s a massive monetary

stimulus, there’s a massive fiscal stimulus. People expect that the news

about the contagion will improve, and that there’s going to be a

vaccine at some point down the line. And there is an element “FOMO”

[fear of missing out]; there are millions of new online accounts —

unemployed people sitting at home doing day-trading — and they’re

essentially playing the market based on pure sentiment. My view is that

there’s going to be a meaningful correction once people realize this is

going to be a U-shaped recovery. If you listen carefully to what Fed

officials are saying — or even what JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs are

saying — initially they were all in the V camp, but now they’re all

saying, well, maybe it’s going to be more of a U. The consensus is

moving in a different direction.

Your

prediction of a weak recovery seems predicated on there being a

persistent shortfall in consumer demand due to income lost during the

pandemic. A bullish investor might counter that the Cares Act has left

the bulk of laid-off workers with as much — if not more — income than

they had been earning at their former jobs. Meanwhile, white-collar

workers who’ve remained employed are typically earning as much as they

used to, but spending far less. Together, this might augur a surge in

post-pandemic spending that powers a V-shaped recovery. What does the

bullish story get wrong?

Yes,

there are unemployment benefits. And some unemployed people may be

making more money than when they were working. But those unemployment

benefits are going to run out in July.

The consensus says the unemployment rate is headed to 25 percent. Maybe

we get lucky. Maybe there’s an early recovery, and it only goes to 16

percent. Either way, tons of people are going to lose unemployment

benefits in July. And if they’re rehired, it’s not going to be like

before — formal employment, full benefits. You want to come back to work

at my restaurant? Tough luck. I can hire you only on an hourly basis

with no benefits and a low wage. That’s what every business is going to

be offering. Meanwhile, many, many people are going to be without jobs

of any kind. It took us ten years — between 2009 and 2019 — to create 22

million jobs. And we’ve lost 30 million jobs in two months.

So

when unemployment benefits expire, lots of people aren’t going to have

any income. Those who do get jobs are going to work under more miserable

conditions than before. And people, even middle-income people, given

the shock that has just occurred — which could happen again in the

summer, could happen again in the winter — you are going to want more

precautionary savings. You are going to cut back on discretionary

spending. Your credit score is going to be worse. Are you going to go

buy a home? Are you gonna buy a car? Are you going to dine out? In

Germany and China, they already reopened all the stores a month ago. You

look at any survey, the restaurants are totally empty. Almost nobody’s

buying anything. Everybody’s worried and cautious. And this is in

Germany, where unemployment is up by only one percent. Forty percent of

Americans have less than $400 in liquid cash saved for an emergency. You think they are going to spend?

Graphic: Financial Times

Graphic: Financial Times

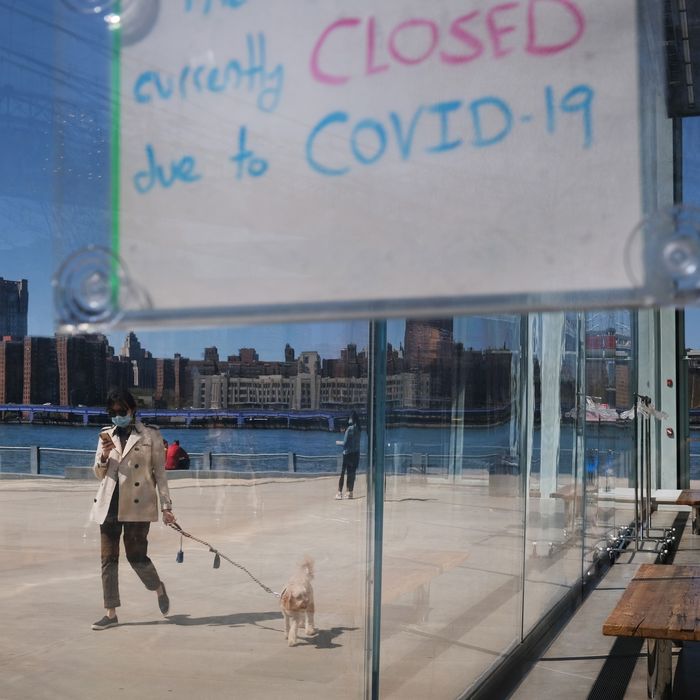

You’re

going to start having food riots soon enough. Look at the luxury stores

in New York. They’ve either boarded them up or emptied their shelves,

because they’re worried people are going to steal the Chanel bags. The

few stores that are open, like my Whole Foods, have security guards both

inside and outside. We are one step away from food riots. There are

lines three miles long at food banks. That’s what’s happening in

America. You’re telling me everything’s going to become normal in three

months? That’s lunacy.

Your

projection of a “Greater Depression” is premised on deglobalization

sparking negative supply shocks. And that prediction of deglobalization

is itself rooted in the notion that the U.S. and China are locked in a

so-called Thucydides trap,

in which the geopolitical tensions between a dominant and rising power

will overwhelm mutual financial self-interest. But given the deep

interconnections between the American and Chinese economies — and warm

relations between much of the U.S. and Chinese financial elite — isn’t

it possible that class solidarity

will take precedence over Great Power rivalry? In other words, don’t

the most powerful people in both countries understand they have a lot to

lose financially and economically from decoupling? And if so, why

shouldn’t we see the uptick in jingoistic rhetoric on both sides as mere posturing for a domestic audience?

First

of all, my argument for why inflation will eventually come back is not

just based on U.S.-China relations. I actually have 14 separate

arguments for why this will happen. That said, everybody agrees that

there is the beginning of a Cold War between the U.S. and China. I was

in Beijing in November of 2015, with a delegation that met with Xi

Jinping in the Great Hall of the People. And he spent the first 15

minutes of his remarks speaking, unprompted, about why the U.S. and

China will not get caught in a Thucydides trap, and why there will

actually be a peaceful rise of China.

Since

then, Trump got elected. Now, we have a full-scale trade war,

technology war, financial war, monetary war, technology, information,

data, investment, pretty much anything across the board. Look at tech —

there is complete decoupling. They just decided Huawei isn’t going to

have any access to U.S.

semiconductors and technology. We’re imposing

total restrictions on the transfer of technology from the U.S. to China

and China to the U.S. And if the United States argues that 5G or Huawei

is a backdoor to the Chinese government, the tech war will become a

trade war. Because tomorrow, every piece of consumer electronics, even

your lowly coffee machine or microwave or toaster, is going to have a 5G

chip. That’s what the internet of things is about. If the Chinese can

listen to you through your smartphone, they can listen to you through

your toaster. Once we declare that 5G is going to allow China to listen

to our communication, we will also have to ban all household electronics

made in China. So, the decoupling is happening. We’re going to have a

“splinternet.” It’s only a matter of how much and how fast.

And

there is going to be a cold war between the U.S. and China. Even the

foreign policy Establishment — Democrats and Republicans — that had been

in favor of better relations with China has become skeptical in the

last few years. They say, “You know, we thought that China was going to

become more open if we let them into the WTO. We thought they’d become

less authoritarian.” Instead, under Xi Jinping, China has become more

state capitalist, more authoritarian, and instead of biding its time and

hiding its strength, like Deng Xiaoping wanted it to do, it’s flexing

its geopolitical muscle. And the U.S., rightly or wrongly, feels

threatened. I’m not making a normative statement. I’m just saying, as a

matter of fact, we are in a Thucydides trap. The only debate is about

whether there will be a cold war or a hot one. Historically, these

things have led to a hot war in 12 out of 16 episodes in 2,000 years of

history. So we’ll be lucky if we just get a cold war.

Some

Trumpian nationalists and labor-aligned progressives might see an

upside in your prediction that America is going to bring manufacturing

back “onshore.” But you insist that ordinary Americans will suffer from

the downsides of reshoring (higher consumer prices) without enjoying the

ostensible benefits (more job opportunities and higher wages). In your

telling, onshoring won’t actually bring back jobs, only accelerate

automation. And then, again with automation, you insist that Americans

will suffer from the downside (unemployment, lower wages from

competition with robots) but enjoy none of the upside from the

productivity gains that robotization will ostensibly produce. So, what

do you say to someone who looks at your forecast and decides that you

are indeed “Dr. Doom” — not a realist, as you claim to be, but a

pessimist, who ignores the bright side of every subject?

When

you reshore, you are moving production from regions of the world like

China, and other parts of Asia, that have low labor costs, to parts of

the world like the U.S. and Europe that have higher labor costs. That is

a fact. How is the corporate sector going respond to that? It’s going

to respond by replacing labor with robots, automation, and AI.

I

was recently in South Korea. I met the head of Hyundai, the

third-largest automaker in the world. He told me that tomorrow, they

could convert their factories to run with all robots and no workers. Why

don’t they do it? Because they have unions that are powerful. In Korea,

you cannot fire these workers, they have lifetime employment.

But

suppose you take production from a labor-intensive factory in China —

in any industry — and move it into a brand-new factory in the United

States. You don’t have any legacy workers, any entrenched union. You are

going to design that factory to use as few workers as you can. Any new

factory in the U.S. is going to be capital-intensive and labor-saving.

It’s been happening for the last ten years and it’s going to happen more

when we reshore. So reshoring means increasing production in the United

States but not increasing employment. Yes, there will be productivity

increases. And the profits of those firms that relocate production may

be slightly higher than they were in China (though that isn’t certain

since automation requires a lot of expensive capital investment).

But

you’re not going to get many jobs. The factory of the future is going

to be one person manning 1,000 robots and a second person cleaning the

floor. And eventually the guy cleaning the floor is going to be replaced

by a Roomba because a Roomba doesn’t ask for benefits or bathroom

breaks or get sick and can work 24-7.

The

fundamental problem today is that people think there is a correlation

between what’s good for Wall Street and what’s good for Main Street.

That wasn’t even true during the global financial crisis when we were

saying, “We’ve got to bail out Wall Street because if we don’t, Main

Street is going to collapse.” How did Wall Street react to the crisis?

They fired workers. And when they rehired them, they were all gig

workers, contractors, freelancers, and so on. That’s what happened last

time. This time is going to be more of the same. Thirty-five to 40

million people have already been fired. When they start slowly rehiring

some of them (not all of them), those workers are going to get

part-time jobs, without benefits, without high wages. That’s the only

way for the corporates to survive. Because they’re so highly leveraged

today, they’re going to need to cut costs, and the first cost you cut is

labor. But of course, your labor cost is my consumption. So in an

equilibrium where everyone’s slashing labor costs, households are going

to have less income. And they’re going to save more to protect

themselves from another coronavirus crisis. And so consumption is going

to be weak. That’s why you get the U-shaped recovery.

There’s

a conflict between workers and capital. For a decade, workers have been

screwed. Now, they’re going to be screwed more. There’s a conflict

between small business and large business.

Millions

of these small businesses are going to go bankrupt. Half of the

restaurants in New York are never going to reopen. How can they survive?

They have such tiny margins. Who’s going to survive? The big chains.

Retailers. Fast food. The small businesses are going to disappear in the

post-coronavirus economy. So there is a fundamental conflict between

Wall Street (big banks and big firms) and Main Street (workers and small

businesses). And Wall Street is going to win.

Clearly,

you’re bearish on the potential of existing governments intervening in

that conflict on Main Street’s behalf. But if we made you dictator of

the United States tomorrow, what policies would you enact to strengthen

labor, and avert (or at least mitigate) the Greater Depression?

The

market, as currently ordered, is going to make capital stronger and

labor weaker. So, to change this, you need to invest in your workers.

Give them education, a social safety net — so if they lose their jobs to

an economic or technological shock, they get job training, unemployment

benefits, social welfare, health care for free. Otherwise, the trends

of the market are going to imply more income and wealth inequality.

There’s a lot we can do to rebalance it. But I don’t think it’s going to

happen anytime soon. If Bernie Sanders had become president, maybe

we could’ve had policies of that sort. Of course, Bernie Sanders is to

the right of the CDU party in Germany. I mean, Angela Merkel is to the

left of Bernie Sanders. Boris Johnson is to the left of Bernie Sanders,

in terms of social democratic politics. Only by U.S. standards does

Bernie Sanders look like a Bolshevik.

In

Germany, the unemployment rate has gone up by one percent. In the U.S.,

the unemployment rate has gone from 4 percent to 20 percent (correctly

measured) in two months. We lost 30 million jobs. Germany lost 200,000.

Why is that the case? You have different economic institutions. Workers

sit on the boards of German companies. So you share the costs of the

shock between the workers, the firms, and the government.

In 2009, you argued

that if deficit spending to combat high unemployment continued

indefinitely, “it will fuel persistent, large budget deficits and lead

to inflation.” You were right on the first count obviously. And yet, a

decade of fiscal expansion not only failed to produce high inflation,

but was insufficient to reach the Fed’s 2 percent inflation goal. Is it

fair to say that you underestimated America’s fiscal capacity back then?

And if you overestimated the harms of America’s large public debts in

the past, what makes you confident you aren’t doing so in the present?

First

of all, in 2009, I was in favor of a bigger stimulus than the one that

we got. I was not in favor of fiscal consolidation. There’s a huge

difference between the global financial crisis and the coronavirus

crisis because the former was a crisis of aggregate demand, given the

housing bust. And so monetary policy alone was insufficient and you

needed fiscal stimulus. And the fiscal stimulus that Obama passed was

smaller than justified. So stimulus was the right response, at least for

a while. And then you do consolidation.

What I have argued this

time around is that in the short run, this is both a supply shock and a

demand shock. And, of course, in the short run, if you want to avoid a

depression, you need to do monetary and fiscal stimulus. What I’m saying

is that once you run a budget deficit of not 3, not 5, not 8, but 15 or

20 percent of GDP — and you’re going to fully monetize it (because

that’s what the Fed has been doing)

— you still won’t have inflation in the short run, not this year or

next year, because you have slack in goods markets, slack in labor

markets, slack in commodities markets, etc. But there will be inflation

in the post-coronavirus world. This is because we’re going to see two

big negative supply shocks. For the last decade, prices have been

constrained by two positive supply shocks — globalization and

technology. Well, globalization is going to become deglobalization

thanks to decoupling, protectionism, fragmentation, and so on. So that’s

going to be a negative supply shock. And technology is not going to be

the same as before. The 5G of Erickson and Nokia costs 30 percent more

than the one of Huawei, and is 20 percent less productive. So to install

non-Chinese 5G networks, we’re going to pay 50 percent more. So

technology is going to gradually become a negative supply shock. So you

have two major forces that had been exerting downward pressure on prices

moving in the opposite direction, and you have a massive monetization

of fiscal deficits. Remember the 1970s? You had two negative supply

shocks — ’73 and ’79, the Yom Kippur War and the Iranian Revolution.

What did you get?

Stagflation.

Now,

I’m not talking about hyperinflation — not Zimbabwe or Argentina. I’m

not even talking about 10 percent inflation. It’s enough for inflation

to go from one to 4 percent. Then, ten-year Treasury bonds — which today

have interest rates close to zero percent — will need to have an

inflation premium. So, think about a ten-year Treasury, five years from

now, going from one percent to 5 percent, while inflation goes from near

zero to 4 percent. And ask yourself, what’s going to happen to the real

economy? Well, in the fourth quarter of 2018, when the Federal Reserve

tried to raise rates above 2 percent, the market couldn’t take it. So we

don’t need hyperinflation to have a disaster.

In

other words, you’re saying that because of structural weaknesses in the

economy, even modest inflation would be crisis-inducing because key

economic actors are dependent on near-zero interest rates?

For

the last decade, debt-to-GDP ratios in the U.S. and globally have been

rising. And debts were rising for corporations and households as well.

But we survived this, because, while debt ratios were high, debt-servicing

ratios were low, since we had zero percent policy rates and long rates

close to zero — or, in Europe and Japan, negative. But the second the

Fed started to hike rates, there was panic.

In

December 2018, Jay Powell said, “You know what. I’m at 2.5 percent. I’m

going to go to 3.25. And I’m going to continue running down my balance

sheet.” And the market totally crashed. And then, literally on January

2, 2019, Powell comes back and says, “Sorry, I was kidding. I’m not

going to do quantitative tightening. I’m not going to raise rates.” So

the economy couldn’t take a Fed funds rate of 2.5 percent. In the

strongest economy in the world. There is so much debt, if long-term

rates go from zero to 3 percent, the economy is going to crash.

You’ve

written a lot about negative supply shocks from deglobalization.

Another potential source of such shocks is climate change. Many

scientists believe that rising temperatures threaten the supply of our

most precious commodities — food and water. How does climate figure into

your analysis?

I

am not an expert on global climate change. But one of the ten forces

that I believe will bring a Greater Depression is man-made disasters.

And global climate change, which is producing more extreme weather

phenomena — on one side, hurricanes, typhoons, and floods; on the other

side, fires, desertification, and agricultural collapse — is not a

natural disaster. The science says these extreme events are becoming

more frequent, are coming farther inland, and are doing more damage. And

they are doing this now, not 30 years from now.

So there is climate change. And its economic costs are becoming quite extreme. In Indonesia, they’ve decided to move the capital out of Jakarta

to somewhere inland because they know that their capital is going to be

fully flooded. In New York, there are plans to build a wall all around

Manhattan at the cost of $120 billion. And then they said, “Oh no, that

wall is going to be so ugly, it’s going to feel like we’re in a prison.”

So they want to do something near the Verrazzano Bridge that’s going to cost another $120 billion. And it’s not even going to work.

The

Paris Accord said 1.5 degrees. Then they say two. Now, every scientist

says, “Look, this is a voluntary agreement, we’ll be lucky if we get

three — and more likely, it will be four — degree Celsius increases by

the end of the century.” How are we going to live in a world where

temperatures are four degrees higher? And we’re not doing anything about

it. The Paris Accord is just a joke. And it’s not just the U.S. and

Trump. China’s not doing anything. The Europeans aren’t doing anything.

It’s only talk.

And

then there’s the pandemics. These are also man-made disasters. You’re

destroying the ecosystems of animals. You are putting them into cages —

the bats and pangolins and all the other wildlife — and they interact

and create viruses and then spread to humans. First, we had HIV. Then we

had SARS. Then MERS, then swine flu, then Zika, then Ebola, now this

one. And there’s a connection between global climate change and

pandemics. Suppose the permafrost in Siberia melts. There are probably

viruses that have been in there since the Stone Age. We don’t know what

kind of nasty stuff is going to get out. We don’t even know what’s

coming.