The U.S. Constitution makes clear that the judiciary has no business second-guessing prosecutorial decisions. That’s what Michael Flynn judge Emmet Sullivan decided to do.

On May 13, Judge Emmet Sullivan issued a blatantly biased and unconstitutional order in the long-lasting Michael Flynn criminal case. To preserve the rule of law and our constitutional separation of powers, the Department of Justice has no choice now but to seek a writ of mandamus from the D.C. Circuit Court ordering the criminal charge against Flynn dismissed and reassigning the case to another judge.

On Tuesday, Judge Sullivan shocked court watchers when he entered an order stating that, “at the appropriate time,” he intended to enter a scheduling order permitting “amicus curiae” or friend of the court briefs to be filed in Flynn case. Flynn, who more than a year ago pleaded guilty to making false statements to the FBI, was seeking to withdraw his guilty plea when the Department of Justice filed a motion to dismiss the criminal charge against Flynn.

The government’s motion to dismiss highlighted new evidence uncovered by an outside U.S. attorney, Jeff Jensen, and detailed the government’s position that even if Flynn had made false statements to FBI agents about his conversations with the Russian ambassador, as a matter of law there was no crime because the false statements were not “material” to a legitimate investigation.

Another Jaw-Dropping Order

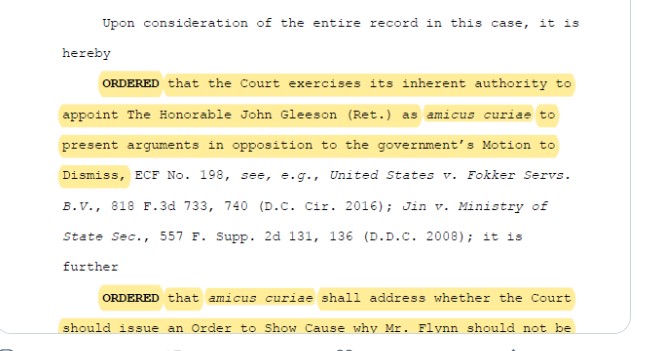

Soon after Judge Sullivan announced he would accept amicus briefs, a group of lawyers operating under the moniker Watergate Prosecutors filed a notice of its intent to file an amicus brief. That a group of left-leaning lawyers intended to relitigate Obamagate via the Flynn case wasn’t surprising. What was surprising—no, unbelievable—is what Judge Sullivan did on Wednesday: He entered an order “appoint[ing] The Honorable John Gleeson (Ret.) as amicus curiae to present arguments in opposition to the government’s Motion to Dismiss.”

This order was jaw-dropping for two reasons. First, the U.S. Constitution makes clear that the judiciary has no business second-guessing prosecutorial decisions. In fact, the very case Judge Sullivan cited for the proposition that he had the inherent authority to appoint an amicus curiae—United States v. Fokker—made clear Sullivan’s order was lawless.

In that case, the government had criminally charged Fokker Services with violations of export control laws. The government and defendant entered a deferred prosecution agreement, under which the government would dismiss the charges in exchange for Fokker Services agreeing to several compliance provisions. But when the parties went before a federal district court judge to formalize the arrangement and a waiver of the Speedy Trial Act, the presiding judge refused to accept the waiver—which in essence doomed the agreement—because he believed the agreement was too lenient on the business owners.

The government filed a “writ of mandamus” with the D.C. Circuit Court. A writ of mandamus is a procedural machination that allows a party to seek to force a lower court to act as required by law. The Fokker court explained that while mandamus is an extraordinary remedy, it is appropriate where the petitioner: (i) has “no other adequate means to attain the relief he desires”; (ii) “show[s] that his right to the writ is ‘clear and indisputable’”; and then “(iii) the court ‘in the exercise of its discretion, must be satisfied that the writ is appropriate under the circumstances.’”

‘The Executive’s Primacy Is Long Settled’

In analyzing the propriety of the district court’s refusal to approve the agreement, the appellate court summarized controlling principles of constitutional law: “The Executive’s primacy in criminal charging decisions is long settled. That authority stems from the Constitution’s delegation of ‘take Care’ duties, U.S. Const. art. II, § 3, and the pardon power, id. § 2, to the Executive Branch. Decisions to initiate charges, or to dismiss charges once brought, ‘lie[] at the core of the Executive’s duty to see to the faithful execution of the laws.’”

Indeed, “[f]ew subjects are less adapted to judicial review than the exercise by the Executive of his discretion in deciding when and whether to institute criminal proceedings, or what precise charge shall be made, or whether to dismiss a proceeding once brought.’”

“Those settled principles,” the court explained “counsel against interpreting statutes and rules in a manner that would impinge on the Executive’s constitutionally rooted primacy over criminal charging decisions.” The Fokker court then specifically addressed Rule 48(a) that “requires a prosecutor to obtain ‘leave of court’ before dismissing charges against a criminal defendant.”

The court explained that “that language could conceivably be read to allow for considerable judicial involvement in the determination to dismiss criminal charges.” However, and significantly, the court then stressed that “decisions to dismiss pending criminal charges—no less than decisions to initiate charges and to identify which charges to bring—lie squarely within the ken of prosecutorial discretion.”

The “leave of court” requirement, the court stressed, “has been understood to be a narrow one—’to protect a defendant against prosecutorial harassment . . . when the [g]overnment moves to dismiss an indictment over the defendant’s objection.’” Such review in that case is to guard against “a scheme of ‘prosecutorial harassment’ of the defendant through repeated efforts to bring—and then dismiss—charges.”

Fokker then concluded: “So understood, the ‘leave of court’ authority gives no power to a district court to deny a prosecutor’s Rule 48(a) motion to dismiss charges based on a disagreement with the prosecution’s exercise of charging authority. For instance, a court cannot deny leave of court because of a view that the defendant should stand trial notwithstanding the prosecution’s desire to dismiss the charges, or a view that any remaining charges fail adequately to redress the gravity of the defendant’s alleged conduct. The authority to make such determinations remains with the Executive.”

This Is Mandatory Precedent

The Fokker decision was a 2016 decision from the D.C. Circuit Court and, as such, establishes “mandatory precedent,” i.e., precedent that must be followed, by all D.C. district court judges—including Judge Sullivan. Thus, Judge Sullivan’s directive that Judge Gleeson, as amicus curiae, should “present arguments in opposition to the government’s Motion to Dismiss,” cannot stand: It conflicts with controlling circuit court precedent, and more significantly with the U.S. Constitution.

While Judge Sullivan has not yet ruled on the government’s Motion to Dismiss, his mere attempt to usurp the executive branch’s authority must be addressed, and now. The government should, as it did in Fokker, seek a writ of mandamus from the D.C. Circuit, directing the charge against Flynn be dismissed.

The government should also seek reassignment of the case on remand, meaning that when the case returns to the lower court for dismissal of the charge, it goes to a different judge. While “reassignment is warranted only in the ‘exceedingly rare circumstance,’” such as where a judge’s conduct is “so extreme as to display clear inability to render fair judgment,” Judge Sullivan’s selection of Judge Gleeson as his “friend of the court” reveals Judge Sullivan’s irretractable bias.

The same day Judge Sullivan named Judge Gleeson to serve in the amicus curiae role, the Washington Post ran an op-ed co-authored by Gleeson, entitled, “The Flynn case isn’t over until the judge says it’s over.” “The Justice Department’s move to dismiss the prosecution of former national security adviser Michael Flynn does not need to be the end of the case—and it shouldn’t be,” he opened. Then, after misrepresenting the Rule 48(b)’s “leave of court” requirement, Gleeson suggests dismissal of the Flynn case would be inappropriate because “the record reeks of improper political influence.”

No, what reeks is Judge Sullivan’s selection of a clearly biased “friend of the court” who appears to have already pre-judged the prosecutor’s motive and found it improper. Judge Sullivan surely knew of Gleeson’s bent and just as surely shares it.

There were several earlier glimpses of Judge Sullivan’s bias, such as when he implied Flynn had committed treason and when he shrugged at the FBI losing the original 302 interview notes. But with his appointment of Judge Gleeson, Judge Sullivan has so far crossed the threshold of fairness, the case should be stripped from his courtroom.