Chuck Todd Is Wrong (Again)

A good leader should balance what the coronavirus-limited 'experts' are arguing for with all other health, safety, security, and well-being concerns.

There are no costs associated with being “overly alarmist” in the face of a global pandemic, “Meet the Press” host Chuck Todd claimed on Sunday. His comment encapsulates the attitude of the media and other elites as they drive people and state and local governments deeper into a panic that has resulted in the loss of tens of millions of jobs, the likely permanent closures of hundreds of thousands of businesses, a general inability to pay rent and other monthly bills, a lack of treatment for non-coronavirus health problems, the closure of churches and schools, the exacerbation of disparities by socio-economic status in educational attainment, disruptions to the supply chain, and the destruction of trillions of dollars of American wealth.

Pushing governors and other politicians to do even more to shut down communities and their economies, Todd asked former North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory, “Are you surprised that more politicians aren’t erring on the side of caution here? Because there seems to be if you’re wrong about this, boy, is that a bad way to be wrong. If, if you’re wrong and you’ve, and you’ve been overly alarmist, well, nobody’s, nobody extra has died. But if you’re wrong and you’ve underplayed, boy, you’ve got a lot to answer for.”

Define ‘Caution’

What Todd portrays as “caution” people should strongly encourage is a radical destruction of systems. Since no one in a position of political authority is arguing for a “let it burn” approach, what Todd portrays as the reckless alternative option is merely the more moderate approach of extreme social distancing and other public health measures such as mask-wearing and continued testing to slow the spread of the virus without closure of nearly everything outside American homes.

Regardless of your feelings about the unprecedented national shutdown plan, it is the less cautious of the two approaches. Some view that as a feature in the war against the coronavirus, while others are worried it might be a dangerous overreaction.

Still, Todd unwittingly reveals the political pressure that many leaders face and the fear that many of them feel about being on the wrong side of expertise. If you follow experts, they reasonably surmise, no one can fault you, even if you destroy the economy. Doing anything other than a continued shutdown runs contrary to what many credentialed experts are instructing, so many leaders follow those experts.

The problem is that the experts who are being listened to so carefully are solely focused on minimizing mal effects from the coronavirus, all other considerations notwithstanding. If that means ending all mammography, colonoscopy and other screenings, so be it. If that means suspending physicals that catch early signs of disease and enable treatment and reversal, so be it. If that means bearing an increase in spousal and child abuse, suicide, and mental health problems, or substance abuse, so be it. If that means setting disadvantaged kids back even further than before the crisis began, so be it. If that means cratering an economy or risking national security, so be it.

A good leader should balance what the coronavirus-limited “experts” are arguing for with all other health, safety, security, and well-being concerns. Too few realize that. What many are doing instead is claiming that they are following “experts” when really they’re only listening to select few epidemiologists. Some put forth extremist platitudes, such as “you can’t have an economy if everyone is dead.”

This problem is exacerbated by a media that incentivizes such narrow thinking. Few if any reporters at the daily White House briefings, much less in countless state and local briefings, have pushed political leaders to explain how they’re balancing non-coronavirus concerns with coronavirus concerns. Our media’s general struggle with providing context, predisposition to sensationalism, longstanding near-exclusive focus on New York City, and unbridled irrational hostility to President Trump have all led to much alarmism. And yes, it does have downsides.

24/7 Hype Machines

To be fair, Todd is not alone in his sentiment, in part because of public health models that projected shocking levels of catastrophic death. Once many in the media finally began paying attention to the Wuhan coronavirus in a non-dismissive way, they swung wildly into another direction of hyping models that predicted millions of dead Americans, and millions of dead in other countries.

The Imperial College study that generated so much attention projected more than 2 million dead Americans if nothing was done, but even 1 million dead Americans if a rigorous “suppression” model weren’t followed until a vaccine might be developed in a couple of years.

All the public health advice given by experts to the media was to “flatten the curve.” There was no stopping the deaths that were to come, we were told, but if they could be slowed down to occur over a longer period of time, that would help hospitals not exceed their capacity by too much, and the pandemic would be less difficult to endure. There is no financial liability for the model-makers for any potential erroneous projections, no matter the chaos they induce. And the acceptance and promulgation of these models did have an effect.

The Projections Are Wildly Inaccurate

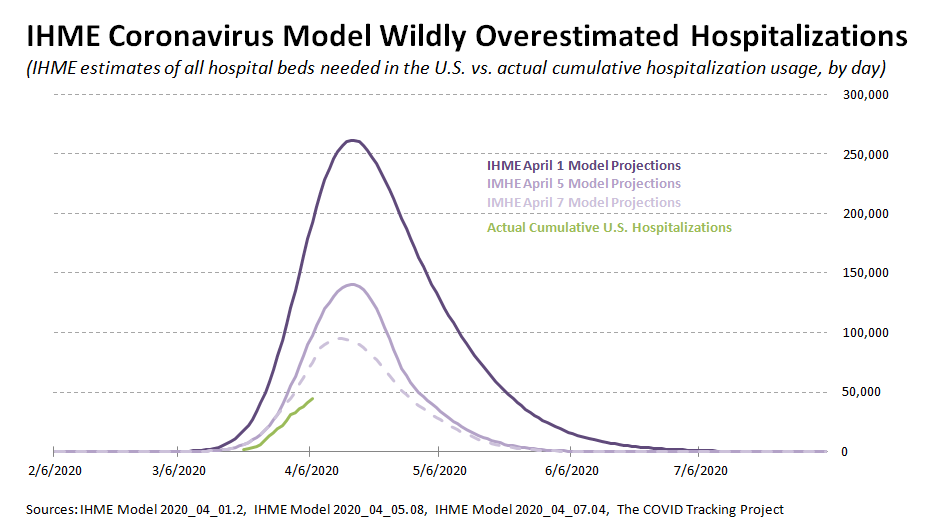

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation has issued state and national projections for hospital capacities, ostensibly to help policymakers plan. Media and governments up to and including the federal government have largely accepted these projections as reasonable.

While the government has been using these projections to set policies, IHME’s projections have routinely been off by a factor of as much as 10. They also fluctuate wildly, almost exclusively in a downward direction. The Institute has at times claimed the discrepancy is a result of the success of social distancing, although all of its models have stated that they assumed “full social distancing through May” even as the projections change.

On April 1, IHME projected that the United States would need a peak of 262,092 hospital beds on April 15. In the latest update, that projection had dropped to a projected peak need of 95,202 beds on April 13. On April 1, the group said the United States would need 38,849 ICU beds and 31,082 ventilators. By April 8, that projection had dropped dramatically to a projected need of 19,438 ICU beds and 16,524 ventilators.

Incidentally, The New York Times repeatedly claimed that the United States would need as many as 1 million ventilators — a tad higher than the current projected nationwide need of 16,524. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said that his experts were leading him to ask for an additional 30,000 ventilators.

President Trump received a great deal of media criticism for questioning whether New York would actually need that many. It turns out that Trump wasn’t just right but really right. On New York’s claimed peak use day of April 7, only 5,038 ventilators were potentially needed, according to the IHME model. The actual use was probably even lower.

Particularly during legitimate global health pandemics such as the one we’re in now, undue alarmism can wreak havoc. Overreacting because of erroneous models, inappropriate reactions to models, or other problems can and absolutely does take place. Scrambling to secure tens of thousands of unnecessary ventilators has costs associated with it, contrary to Todd’s claim that alarmism has no downsides.

Not only is there just the cost of ramping up production for ventilators that won’t be used, and the opportunity cost of those factories not producing something more useful, there are the problems caused by governors competing with each other for ventilators, driving up the cost. Also, the panic about lack of ventilators further entrenches community shutdown with its previously noted heavy costs. And ventilators are just one tiny example.

Media Initiate, Strengthen, Perpetuate Economic Debacle

Todd’s show was built around a quote from Amy Acton, director of public health in Ohio. “She said this on March 13th. And [U.S. Surgeon General, Vice] Admiral [Jerome Adams], it has been haunting me ever since. And this is what she said. ‘On the front end of a pandemic, you look a little bit like an alarmist. You look a little bit like a Chicken Little. The sky is falling. And on the back end of a pandemic, you didn’t do enough.’ Are those words that we should all be living by, which is you may be hesitant right now if you’re a leader about debating health versus the economy, hindsight you’re going to wish you had done more?”

These words comfort those who encourage extremely strong measures in the face of pandemic, and there is definitely truth to them. When faced with unforeseen situations, it is extremely wise to over-prepare. Further, it is at least arguably difficult to get large populations to appropriately prepare or work to prevent problems without overstating the need. But that doesn’t mean there is no reasonable limit to the amount of preparation.

The notion that there are no risks to a panicked response to a global pandemic is absurd and nonsensical on its face. The notion that there are no downsides to extreme government action is something even our scandal-driven media would deny.

Taken to an extreme, you could have military patrolling in the streets to ensure more social distancing. The Chinese government welded families into their homes, sealing doors to keep them inside, for crying out loud. The United States absolutely could be doing more to further flatten the curve. The fact that we are not shows that we know that there are costs to certain actions, many of which are not acceptable.

So the question isn’t whether there are costs associated with our actions but whether they are justified. The real costs of alarmism are clear, and we’re seeing them in hospital staff being furloughed, unemployment lines getting longer, businesses being shut down, and disadvantaged children not getting their education. It could be that once the tally is calculated, people will decide the costs were more than worth it. It is odd, however, that media aren’t willing to engage in the conversation about the appropriate cost to endure.

Further, as the hospital projections — and even death projections — change radically, continuing to be dropped drastically down day after day, it is imperative that we have the discussion about the costs of continued lockdown.

Alarmism Has Serious Downsides

The radical steps being taken by political leaders and encouraged uncritically by the media may be justified, even as the dire predictions continue to be overstated. But Todd’s refusal to even acknowledge the possibility of downsides to alarmism, much less the very real downsides that are already on display, is journalistic malpractice. It could also lead to further erosion of already cratering public confidence in institutions including the media.

Tucker Carlson recently said, “If the coronavirus shutdown was crushing college administrators or nonprofit executives or green energy lobbyists, it would have ended last week. Instead, it’s mainly service workers and small business owners who have been hurt, and they’re not on television talking about what they’re going through. You need to look closely to see their suffering.”

The relatively privileged status of our media might make their endurance of the community shutdown easier to bear. They should not be fooled, however, into thinking that there is no downside to their preferred path.