New facts in the Michael Flynn case call into question the voluntariness of Flynn’s plea. Judge Sullivan should dismiss the charges to send a clear message: Outrageous prosecutorial coercion will not be tolerated.

The criminal case against Michael Flynn imploded Friday. First, the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia provided Flynn’s legal team with documents discovered by an outside review of the Flynn prosecution — documents withheld for years. Then, Sidney Powell, the attorney who took over Flynn’s defense nearly a year ago, filed new documents in the case, revealing a secret “lawyers’ understanding” not to prosecute Flynn’s son if the retired lieutenant general pleaded guilty.

The criminal case against Flynn began when President Donald Trump’s former national security adviser pleaded guilty Dec. 1, 2017, to lying to the FBI about conversations he’d had with the Russian ambassador following Trump’s election. That case, initiated by the now-disbanded special counsel’s office, lingered for more than a year while Flynn cooperated with Robert Mueller’s team. An end seemed near when Flynn appeared before presiding federal Judge Emmet Sullivan on Dec. 18, 2018, for sentencing. But after Sullivan harshly rebuked Flynn and suggested Flynn might spend time in jail, the retired lieutenant general accepted the longtime judge’s offer to have the sentencing hearing continued until Flynn’s cooperation was complete.

Things remained static until Mueller announced on May 29, 2019, that “the investigation was complete, and that the special counsel’s office had been closed.” One week later, Flynn fired his Covington & Burling lawyers, Robert Kelner and Stephen Anthony, and replaced them with Powell.

Powell, a vocal critic of the Mueller investigation, filed a flurry of motions seeking, among other things, documents she maintained the government had improperly withheld; she also sought dismissal of the indictment for prosecutorial misconduct. Sullivan denied Powell’s motions and set a new sentencing date of Jan. 28, 2020.

Flynn Withdraws His Guilty Plea

But before the hearing date arrived, federal prosecutor Brandon L. Van Grack — a holdover from the special counsel’s office — filed a supplemental sentencing memorandum in the case, reversing the government’s position that Flynn was entitled to a sentencing reduction for providing substantial assistance to the prosecutors.

Flynn’s legal team responded by filing a motion to withdraw the guilty plea, arguing the government breached the plea agreement by pulling its recommendation for a substantial assistance sentencing reduction. Powell filed two more motions to withdraw shortly thereafter, one based on prosecutorial misconduct and the second based on claims that Flynn’s prior Covington attorneys had a non-waivable conflict of interest and provided ineffective assistance of counsel.

Sullivan delayed sentencing once more and directed Flynn’s former attorneys to provide material to the government related to Flynn’s ineffective assistance claims. Then came news that Attorney General William Barr had appointed the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri, Jeffrey Jensen, to review the special counsel’s handling of the Flynn case.

How Federal Prosecutors Sidestepped Legal Requirements

On Friday, in what appears to be the first official confirmation of the details of that appointment, the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, Timothy Shea, dispatched a letter to Flynn’s attorneys. The letter opened by informing Powell’s team that in January 2020, Barr had directed Jensen to conduct “a review of the Michael T. Flynn investigation.” That review, Shea explained, “has involved the analysis of reports related to the investigation along with communications and notes by Federal Bureau of Investigation (‘FBI’) personnel associated with the investigation.” Enclosed with the letter were an unknown number of documents “obtained and analyzed” by Jensen’s team in March and April. “Additional documents may be forthcoming,” the letter explained, concluding that the material provided was covered by the court’s protective order.

While the documents remain blocked from public view, Powell’s Friday court filing — captioned as a “Supplement to Mr. Flynn’s Motion to Dismiss for Egregious Government Misconduct” — portrayed the previously withheld material as explosive. “This afternoon,” Powell wrote, “the government produced to Mr. Flynn stunning Brady evidence that proves Mr. Flynn’s allegations of having been deliberately set up and framed by corrupt agents at the top of the FBI.”

“It also defeats any argument that the interview of Mr. Flynn on January 24, 2017 was material to any ‘investigation,’” Flynn’s attorney wrote.

Powell filed this recently received evidence under seal as Exhibit 3 but requested the court “order the government immediately to provide the defense with unredacted copies of the documents in Exhibit 3,” and that it promptly unseal those documents. Whether the Department of Justice will object to the unsealing of the documents remains to be seen, but we should know shortly.

Also attached to the filing were two heavily redacted exhibits that consisted of email communications between Flynn’s former Covington attorneys. “We have a lawyers’ unofficial understanding that they are unlikely to charge Junior in light of the Cooperation Agreement,” one email read, referring to Flynn’s son, also named Michael Flynn.

While alone that reference may not have raised concerns of misconduct, the second excerpt suggests prosecutors sought to hide evidence from other defendants by keeping the Michael Flynn Jr. part of the deal secret. “The government took pains not to give a promise to [defendant Flynn] regarding Michael Jr., so as to limit how much of a ‘benefit’ it would have to disclose as part of its Giglio disclosures to any defendant against whom MTF may one day testify,” Flynn’s attorney wrote.

To date, Sullivan has seemed unmoved by claims of prosecutorial misconduct, but that an outside U.S. attorney discovered documents he believed should be provided to Flynn’s legal team may change Sullivan’s perspective. If not, the email exchanges suggesting the special counsel’s team attempted to circumvent the disclosures constitutionally required under Giglio — more on that below — by forging a secret “lawyers’ understanding” not to charge Michael Jr. may just jolt the federal judge’s sense of justice.

The revelation of a “lawyers’ understanding,” after all, concerns much bigger questions than just Flynn’s guilty plea. It raises the specter of widespread abuse by federal prosecutors of the plea process to sidestep constitutional requirements. That’s what Giglio is: a constitutional mandate that the prosecution provide an accused with material evidence affecting the credibility of a government’s witness.

The Role of Giglio in Flynn’s Case

When a defendant cuts a deal with the government and agrees to cooperate and testify against a co-defendant or others, under Giglio those other defendants are entitled to learn the benefit of the plea agreement. But the email excerpts above suggest, as Powell argued in her latest filing, that the lead prosecutor, Van Grack, “made a side deal not to prosecute Michael G. Flynn [Jr.] as a material term of the plea agreement, but he required that it be kept secret between himself and the Covington attorneys expressly to avoid the requirement of Giglio.”

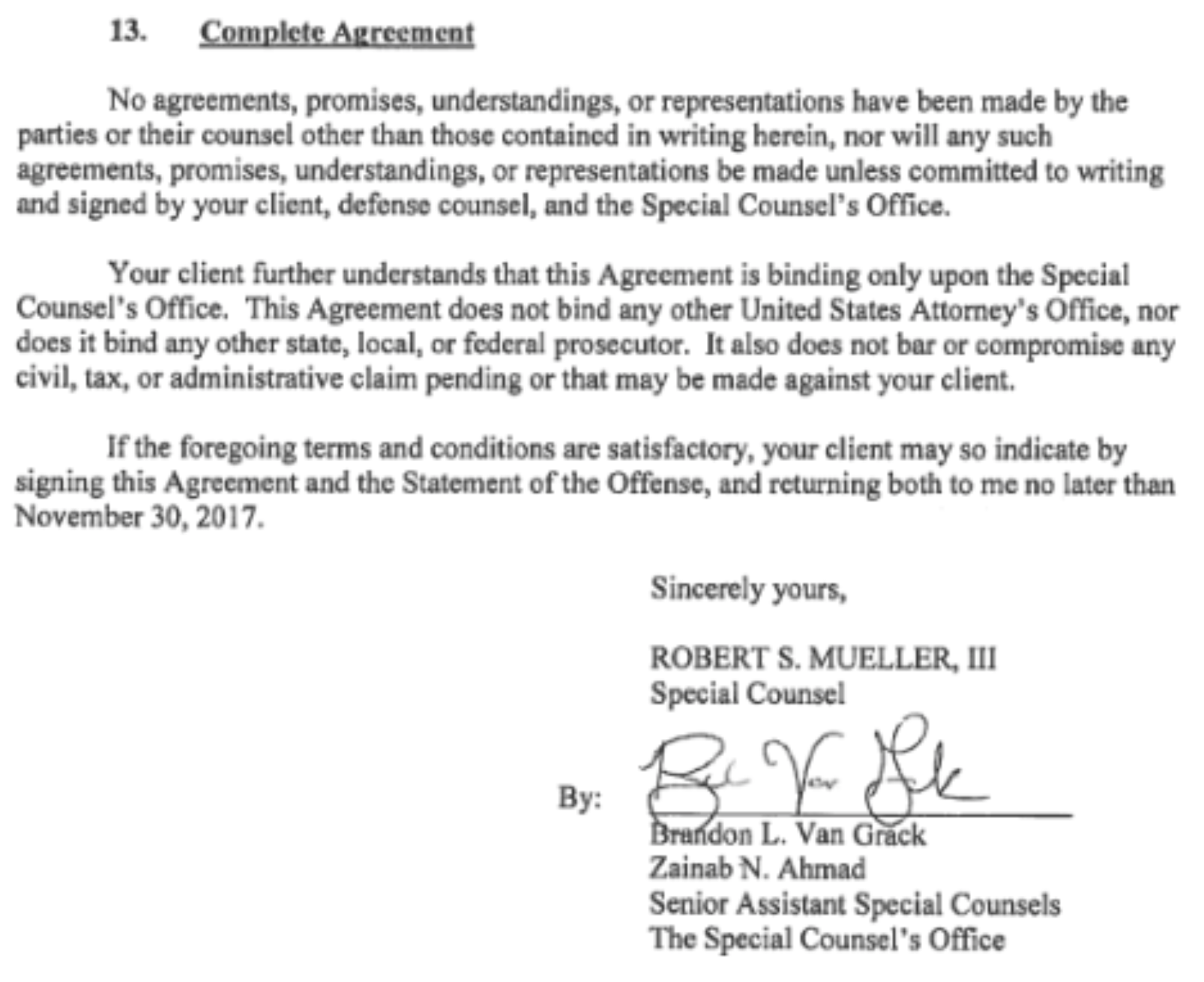

Those emails also distinguish Flynn’s case from the run-of-the-mill criminal case in which a defendant seeks to avoid a plea agreement because of a side deal. Courts regularly dismiss such challenges because the terms of the plea agreement expressly provide that there are no other agreements beyond those set forth in the written plea agreement. As typical, Flynn’s plea agreement included such a provision, as seen below.

Facts of Flynn Case Reveal Government Misconduct

But Flynn’s case is different for two reasons. First, the emails attached as Exhibits 1 and 2 in Friday’s filing provide evidence of a side agreement — something lacking in most criminal cases. Second, the emails suggest the government intended to bind itself to this commitment via a “lawyers’ understanding” and omitted the term from the written plea agreement for an improper purpose — to avoid the constitutionally mandated disclosures. Thus, in this case, the side agreement implicates the integrity of the judicial process and suggests prosecutorial misconduct.

The emails also support Flynn’s argument that the prosecutors wrongfully threatened to prosecute his son to coerce the elder Flynn to plead guilty to a crime he did not commit. Here it is important to recognize that threats to prosecute third parties during plea negotiations are not necessarily unconstitutional or even improper. The case law makes clear, however, that such bargaining “can pose a danger of coercion,” and “where the threatened prosecution pertains to those with whom the defendant has familial ties or other close bonds, the threat of coercion is much greater.” Thus, in using such tactics, courts require the government to abide by “a high standard of good faith,” which at a minimum requires probable cause to prosecute a family member.

Further, the Supreme Court has cautioned that where plea bargains involve “adverse or lenient treatment for some person other than the accused,” it “might pose a great danger of inducing a false guilty plea by skewing the assessment of the risks a defendant must consider.” Thus, courts have noted that “a plea agreement entailing lenity to a third party imposes a special responsibility on the district court to ascertain [the] plea’s voluntariness … due to its coercive potential.”

That the special counsel’s office omitted any reference of “lenity” to Flynn’s son in the plea agreement reeks of bad faith and suggests Mueller’s team lorded a threat of prosecution over the younger Flynn to coerce the elder to plead guilty. This conclusion is supported by the government’s behavior following a falling out between Powell and the lead prosecutor Van Grack.

After Powell informed Van Grack that Flynn would not testify that he had knowingly filed false Foreign Agent Registration Act statements in the government’s criminal case against Flynn’s former business partner, prosecutors added Flynn Jr. as a last-minute witness in that criminal case. The prosecutors, however, never called Flynn Jr. to the stand, suggesting it was a scare tactic to get Dad back in line. Likewise, after the breakdown between the prosecutors and Flynn, an FBI agent contact Flynn Jr. directly even though Flynn Jr. had an attorney.

These facts call into question not just the government’s conduct, but the voluntariness of Flynn’s plea. But because there was no mention in the official plea deal of any agreement not to charge Flynn Jr., the court had no opportunity to exercise its “special responsibility to ascertain the plea’s voluntariness.”

With these facts now known, it seems unfathomable that Judge Sullivan will reject Flynn’s motion to withdraw his guilty plea. But Sullivan should do more: He should dismiss the charges against Flynn to make clear that outrageous prosecutorial misconduct will not be tolerated.