When you write in 'American' on the census, you acknowledge that while our differences are part of us, they don't compare with all we have in common.

On St. Patrick’s Day, my children and I dressed in green. We ate corned beef and cabbage, as we do every year. I listened to Irish music, read Irish history, and even enjoyed Irish cuisine. I’m too old for the bar scene on St. Paddy’s, but they were all shut down this year anyway, along with the parades. Still, for me and my family, it is a day on which we acknowledge our Irish roots.

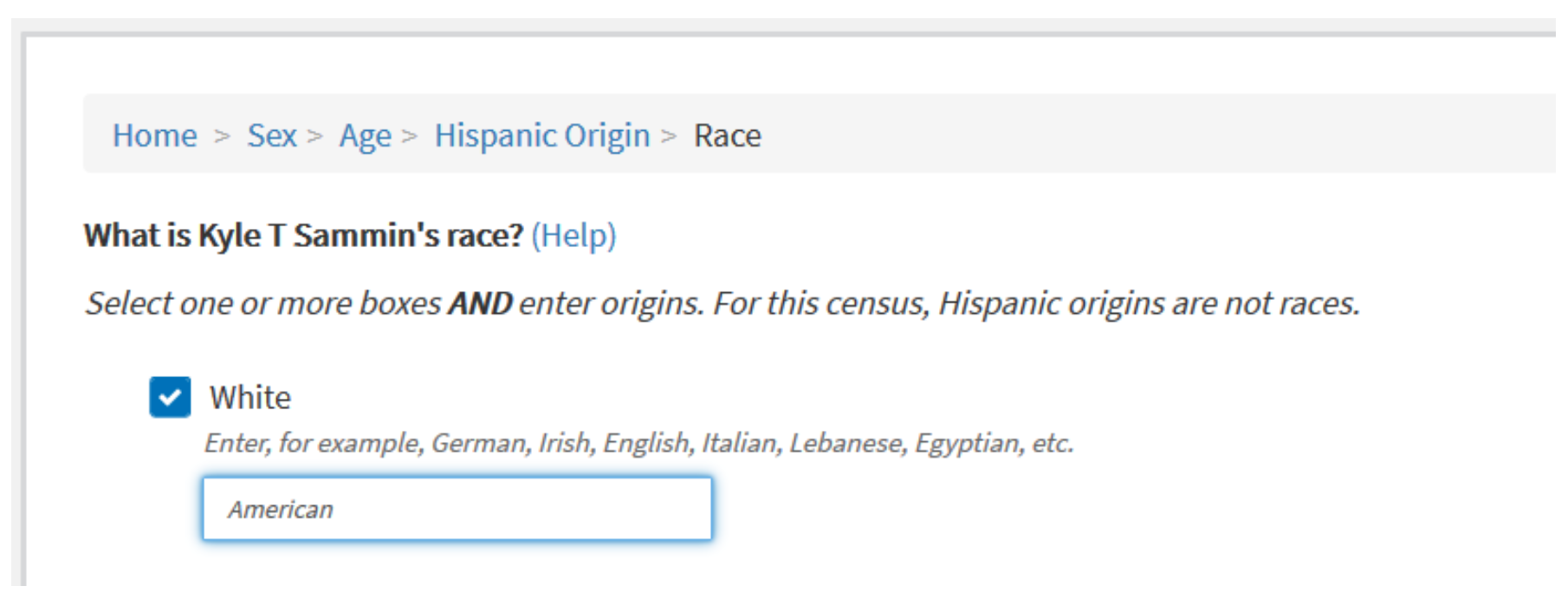

The next day, I filled out the 2020 United States census. Question No. 9 addressed race, as every census has since 1790. This year, there’s an added twist: After checking off “white,” I was asked to fill in my “origins.” I typed the same answer for myself, my wife, and my children: American.

The contrast between these two paragraphs might jump out at you, but to me it reveals the flaw in the question of origins. Some of my ancestors did, indeed, come from the Emerald Isle and travel by boat to these shores. But some of them came from other places. That’s true of most Irish Americans I know. We’re not fully Irish — not in ancestry and certainly not in spirit. We are fully American, though. Our origins, whatever that means, are in this country as a part of this American culture.

The Census Department’s website says, “Your answer to this question should be based on how you identify,” a thoroughly postmodern view of race and ethnicity. It’s also a definition guaranteed to cause problems since “identity” is a lot different from “origins.” One is a feeling, while the other is closer to a fact.

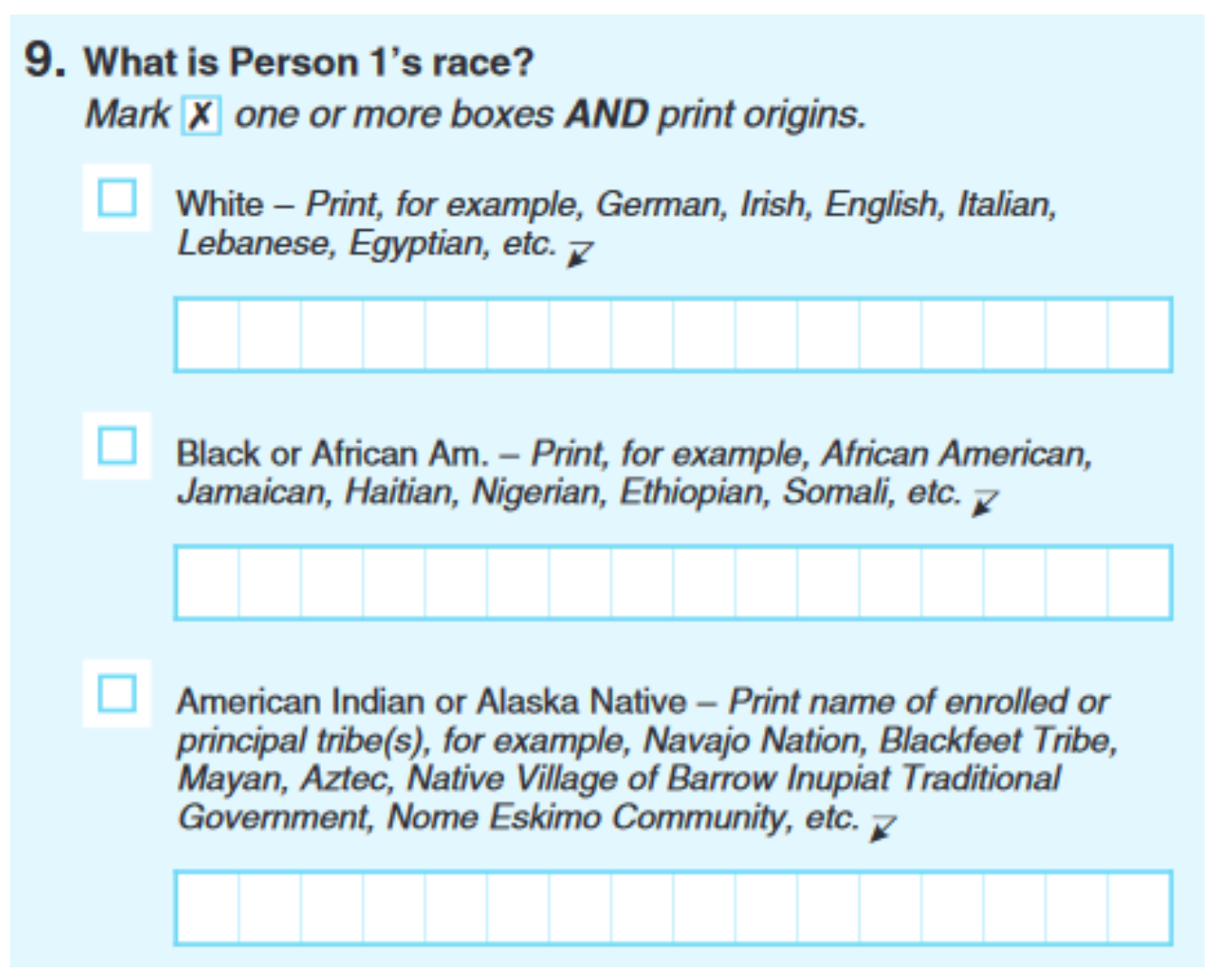

The more I thought about the question, the harder it was to answer. We are told to enter, “for example, German, Irish, English, Italian, Lebanese, Egyptian, etc.” While the online form above might have allowed enough room to list all the nations from which my ancestors sprang forth, the paper form below was more restricted.

Was there room for every branch of the family tree when so many people have mixed ancestry? This led me to consider the question perhaps more deeply than the Census Department had intended. Could anyone really consider himself as having “origins” in the fourth or fifth country on his list? As those immigrant roots grow more distant, how much do they really count in one’s “identity”? For many 21st-century Americans, any connection with the old country is almost theoretical by now.

For more recent immigrants, the question would have been simpler. My great-grandfather’s origins were on a farm in western Ireland. He became an American citizen, so the question “Where are you from?” would have been easy for him: Ireland. Since then, my family has identified as Irish, with other ancestries added along the way. After four generations of the American experience, however, the connections are less sure.

My last immigrant ancestor died in 1966, more than a decade before I was born. I’ve never been to Ireland. I don’t hold dual citizenships. Even my Irish traditions — such as corned beef, a dish served by Irish Americans, not Irishmen — are all filtered through American culture. Thinking hard enough about this question, it occurred to me that my origins are here.

Connections Fade as Generations Pass

This is even truer of my wife and children. My wife’s most recent European immigrant ancestor came here about 1820, and most came far earlier. With which European nation is she meant to identify after two centuries of ancestors living in the New World? The longer families are here, the murkier their origins become. Those who arrived here centuries ago came to a place with little bureaucracy and spotty record-keeping. Immigrant origins are preserved only within families, if at all.

The 2010 census did not ask about origins, but the 2000 census did, with 20 million Americans reporting their ethnicity as “American.” They are a growing slice of the population that identifies as American only, either because they don’t know where their ancestors came from or because they feel no real connection to any country but this one.

That number will increase in 2020. I’m the family genealogist, and even I don’t know exactly where some of my ancestors come from. Millions of Americans are saying the same. But it’s more than an admission of ignorance: Many people are asserting that there is an American culture and that we are members of it.

We’re Looking At This the Wrong Way

That people fill in “American” for their origins, and that they have been doing so for years, shows the flaw in the whole question. While it is interesting to know where a person’s ancestors originated, is it a matter of interest to the government? If so, should the question of origins be mixed up with the question of race?

A larger problem with the question is that filling in “American” is mostly an option for white people, when really it should be something Americans of any race can claim. A similar fill-in-the-blank section exists for people who list their race as black, and Native Americans are supposed to fill in their tribe. But for Asian Americans, the only option is to choose from a variety of Asian nationalities. Why should American origin be denied to anyone born in America, whatever his or her race?

An American identity exists, and it transcends old-fashioned ideas about race. That identity has some of its roots in Europe, but it also draws on all the other cultural traditions blended within our borders, creating something different from any of them. Rich Lowry said in his 2019 book, “The Case for Nationalism,” “[A]n American cultural nationalism is an inclusive nationalism.” If you’re here, American culture is open to you, regardless of your race or ethnicity.

If the culture is open to everyone, and if anyone in America can claim American origins, what is the point of writing it down on a form? A better inquiry: What is the point of this census question in the first place? We come from many different places, but we become one culture. Any Irish-descended American has more in common with his neighbor of a different ethnicity than he does with some distant relation on the other side of the ocean.

So why ask the question at all?

For that matter, it’s worth asking why we demand that people categorize themselves by race in the first place. Race exists, and it has an effect on our lives, but the government need not play a part in separating us from each other this way. In France, the government has steadfastly refused to sort citizens by race. French citizens are French citizens — that’s it.

America should consider a similar course. In the meantime, removing this increasingly antiquated question of origins would be a good start. Our differences are a part of us, but after a while, they amount to little compared with all we have in common. When you write in “American” on the census, you acknowledge this and act to embrace your own culture, not that of your ancestors.