While this evidence provides his attorney a solid argument that the prosecution sought to push Michael Flynn to lie, that might not be enough to carry the day with Judge Sullivan.

Yesterday, Michael Flynn’s attorney, Sidney Powell, filed a Motion to Withdraw his Guilty Plea, arguing the government breached its obligations under the plea agreement the retired general had entered with the special counsel’s office in late 2017. Prosecutors had promised in that plea agreement to “file a departure motion pursuant to Section 5K1.1 of the Sentencing Guidelines” if Flynn provided substantial assistance to the government.

The government kept that pledge—until it didn’t.

On December 4, 2018, prosecutors working for the special counsel’s office filed a Memorandum in Aid of Sentencing, stating that the government has moved for a downward departure pursuant to Section 5K1.1, to reflect Flynn’s “substantial assistance to the government.”

Section 5K1.1 authorizes a judge to depart from the sentencing guideline—a set of standards used to assess an appropriate sentencing range for a defendant—if the government files a motion “stating that the defendant has provided substantial assistance in the investigation or prosecution of another person who has committed an offense . . .” A court cannot depart from the guidelines under Section 5K1.1, unless the prosecution files such a motion.

The government reiterated its position on December 18, 2018, at Flynn’s originally scheduled sentencing hearing. “Mr. Flynn should receive probation,” prosecutors said, with lawyer Brandon Van Grack, who represented the special counsel’s office, “thoroughly prais[ing] Mr. Flynn, telling the court: ‘I’d like to highlight that General Flynn has held nothing back, nothing in his extensive cooperation with the Special Counsel’s Office. He’s answered every question that’s been asked. I believe they feel that he’s answered them truthfully, and he has. He’s complied with every request that’s been made, as has his counsel. Nothing has been held back.”

Prosecutors added that Flynn had “provided substantial assistance to the attorneys in the Eastern District of Virginia in obtaining th[e] charging document” for its prosecution of Flynn’s former business partner, Bijan Rafiekian.

But a week ago, in its Supplemental Memorandum of Sentencing, prosecutors reneged on their promise. After acknowledging in the opening paragraph of its memorandum that “it filed a motion for a downward departure pursuant to Section 5K1.1,” for substantial assistance, government attorneys asserted they were “no longer moving for a departure under U.S.S.G.§ 5K1.1 for providing substantial assistance to the government.”

That’s a problem, because prosecutors already admitted that Flynn had provided substantial assistance to the government “in obtaining th[e] charging document” for the prosecution of Flynn’s former business partner, and the plea agreement requires the government to file a 5K1.1 motion if Flynn provided substantial assistance. Further, there is nothing in the plea agreement that purports to provide the government with the power to withdraw a 5K1.1 motion for substantial assistance.

In short, the government breached the plea agreement.

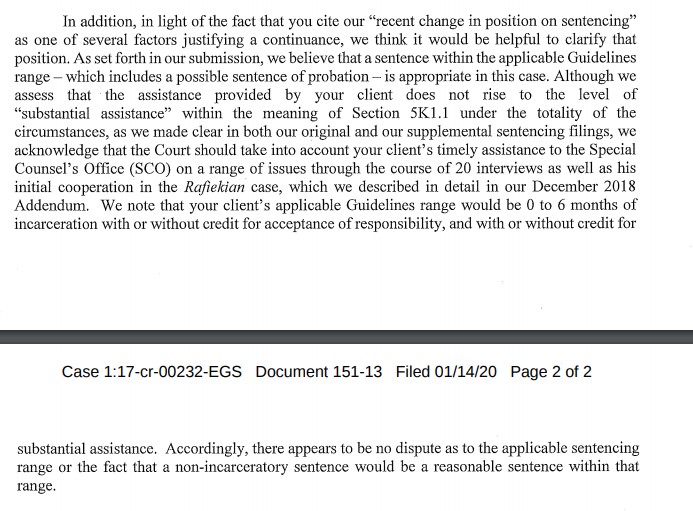

Realizing their misstep, prosecutors dispatched a last-minute letter to Powell on Monday, seeking to “clarify” their position. The government attorneys first framed their refusal to support a 5K1.1 reduction as based on their “assessment” of Flynn’s assistance “under the totality of the circumstances.” Prosecutors, however, then quickly pivoted to a question of prejudice, suggesting that since Flynn’s guideline range would remain 0 to 6 months with or without credit for substantial assistance, there’s no dispute.

But there is. The government can’t “have its cake and eat it too,” as Powell put it: “The government breached the plea agreement when it filed the new sentencing memo,” withdrawing the previously filed—and required—5K1.1 substantial assistance motion.

Whether presiding Judge Emmett Sullivan will agree, however, is another question. His 90-plus page opinion denying, in its entirety, Powell’s previously filed motion to compel the production of Brady material, suggests he is done with this case. And a footnote dropped amongst the tedious legal trappings suggests Judge Sullivan has already bought the prosecutors’ claim that Flynn had backed out on his agreement to cooperate in the case against his former business partner, Rafiekian, who was later acquitted.

“Flynn admitted that he made materially false statements and omissions in the FARA filings,” Judge Sullivan wrote, referring to the Foreign Agents Registration Act. Sullivan continued: “Months later, however, Mr. Flynn’s new counsel represented that she ‘advised the prosecutors [in Rafiekian’s case] that Mr. Flynn did not know and did not authorize signing the FARA form believing there was anything wrong in it. [Flynn] honestly answered the questions his former counsel posed to him to the best of his recollection, and with the benefit of hindsight.”

Judge Sullivan then quoted several passages in which Powell made clear that while Flynn “accepted responsibility for the inaccuracies in the FARA filings,” he never reclaimed he “willfully allowed the filing to proceed—knowing and intending it to deceive or mislead.”

The tenor of Judge Sullivan’s text screeched disbelief. The long-time federal judge might as well have said that Flynn’s fancy new attorney was playing word games reminiscent of “it depends what the meaning of is, is.” But Powell’s Motion to Withdraw provides proof to back up Flynn’s claim that he did not file the FARA knowing it contained inaccuracies.

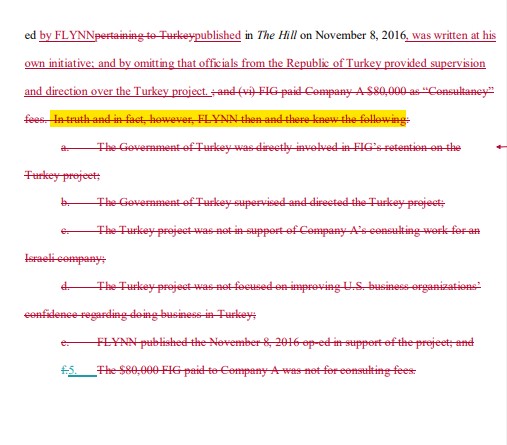

Specifically, Powell filed a copy of the draft statement of offense that establishes that an earlier version of that document included a statement that when the FARA statement was filed, “in truth and in fact, however, Flynn then and there knew” the truth about the details misrepresented in the filling. That language was deleted in the final version of the statement of offense to which Flynn agreed.

That deletion is huge: It shows that Powell isn’t playing word games—the government is.

The government knew that Flynn objected to that characterization of the FARA filing and prosecutors agreed to delete that language from the statement of offense. Yet they then demanded Flynn testify at his former business partner’s trial that he knew at the time the FARA filings were submitted that they were fraudulent. When Flynn refused, the government cast him as a co-conspirator and reneged on its promise to seek a reduction for substantial assistance.

While this evidence provides Powell a solid argument that the prosecution sought to push Flynn to lie, that might not be enough to carry the day with Judge Sullivan. But, as Powell’s memorandum made clear, she is not nearly close to done defending Flynn—she just needs more “time to brief many alternate reasons for the withdrawal of his plea.”