Article by Charles Silver and David A. Hyman:

When the massive new health program known as Medicare was created in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson got health care providers on board by buying their support: He promised that the government would let them decide how much to charge and which services to deliver. In many countries with single-payer health systems, governments decide how much they will pay; when adopting Medicare, the U.S. let providers make that decision. It gave doctors and hospitals the keys to the U.S. Treasury and guaranteed their profits.

When the massive new health program known as Medicare was created in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson got health care providers on board by buying their support: He promised that the government would let them decide how much to charge and which services to deliver. In many countries with single-payer health systems, governments decide how much they will pay; when adopting Medicare, the U.S. let providers make that decision. It gave doctors and hospitals the keys to the U.S. Treasury and guaranteed their profits.

Spending went through the roof as “unrestricted cost reimbursement became the modus operandi for financing American medical care.” The costs wildly exceeded the government’s expectations at the time: A 1967 estimate by

the House Ways and Means Committee predicted that, in 1990, Medicare’s

total cost would be $12 billion. The actual cost was $98 billion—eight

times as much.

Half a century later, we are still living with the consequences of the decision to put providers in charge of the payment system. A recent study by scholars at Johns Hopkins University estimated that in 2018, fully “48 percent of the entire U.S. federal budget” was spent on health care. That isn’t a typo, and it’s not an accident either: Industry groups lobby the government around the clock to maximize the number of taxpayers’ dollars they receive.

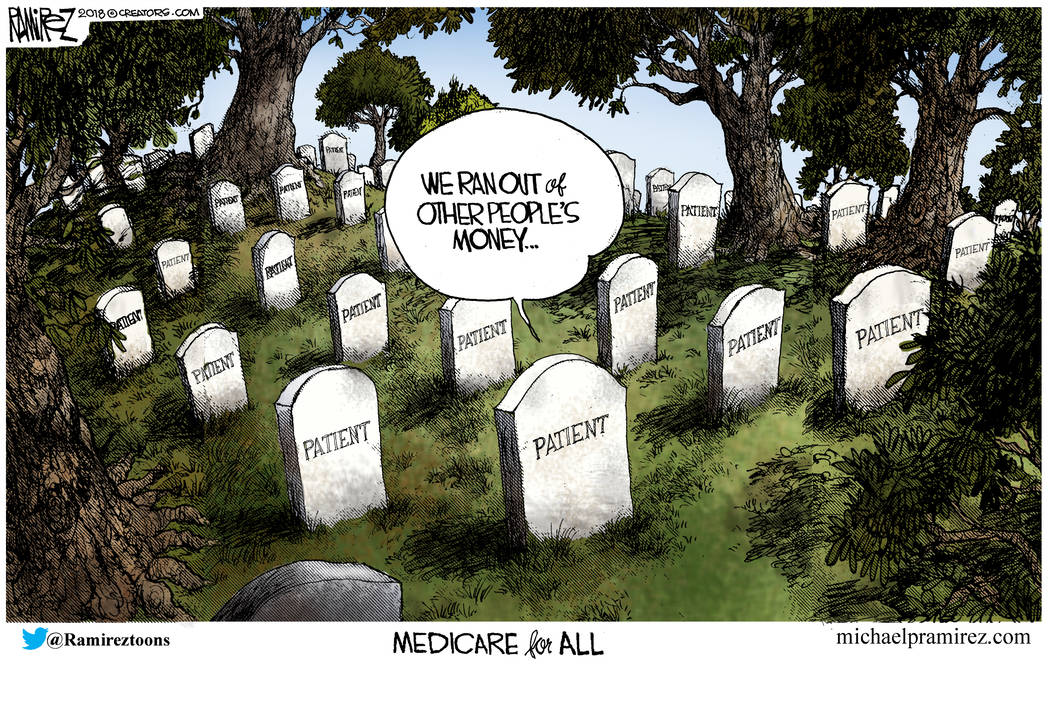

Medicare for All’s supporters promise that this time will be different. Once a single-payer program is implemented, they argue, the government will save billions of dollars by slashing payments to drug-makers, doctors, and hospitals.

Consider how, in recent years, a few attempts to save money fared:

Medicare for All is also certain to drive up spending by generating an enormous surge in demand for medical care. The bills pending in Congress promise soup-to-nuts coverage for free. Premiums, deductibles and copays are supposed to vanish. If that happens, prodigious consumption of medical services will be inevitable.

The fundamental problem is that Medicare for All’s supporters have cause and effect reversed. They think Americans need universal comprehensive coverage because health care is expensive. In reality, we spend too much on health care because we rely so heavily on third parties—Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers—to pay our bills. In 1960, when patients paid about $1.73 out of pocket for every $1 paid by an insurer, health care spending per capita was $165. In 2010, when patients paid out 16 cents for every insurance dollar, spending per capita was $8,400. And in 2017, when the ratio was 14 cents out of pocket for every insurance dollar, spending per capita was $10,740. The more we rely on third party payers, the more we spend. Because the full-on, government-run, single-payer plans introduced by Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren will reduce out of pocket costs to zero, they will drive spending to new heights.

Half a century later, we are still living with the consequences of the decision to put providers in charge of the payment system. A recent study by scholars at Johns Hopkins University estimated that in 2018, fully “48 percent of the entire U.S. federal budget” was spent on health care. That isn’t a typo, and it’s not an accident either: Industry groups lobby the government around the clock to maximize the number of taxpayers’ dollars they receive.

Medicare for All’s supporters promise that this time will be different. Once a single-payer program is implemented, they argue, the government will save billions of dollars by slashing payments to drug-makers, doctors, and hospitals.

Although cuts of that magnitude

would severely affect patient care, there’s no need to worry. If past is

prologue, they will never occur. Time after time, providers have

blunted initiatives designed to economize at their expense. There’s no

reason to think this Congress will succeed when virtually every past

Congress has failed to reduce the flow of Medicare dollars.

- In 1997, Congress tried to rein in spending increases by tying Medicare spending on physicians’ services to something called the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula. Whenever payments to doctors grew faster than GDP, the SGR was supposed to reduce them automatically. The formula triggered payment cuts in 2003 and every subsequent year—but the cuts never happened. Under pressure from physicians, Congress adopted a series of “doc fixes” that delayed them and often gave doctors a raise. Finally, in 2015, when the SGR formula required payment cuts of roughly 25 percent, Congress repealed it entirely, plowed the whole cost of doing so into the budget deficit, and guaranteed raises for doctors through (at least) 2019.

- In 2019, the industry used lawsuits to put the kibosh on three money-saving initiatives. First, the Trump administration’s attempt to require drug-makers to include list prices in consumer-directed advertisements went down in flames when a federal judge decided that the Department of Health and Human Services lacked the power to impose it. Then, the administration’s attempt to save $3 billion to $4 billion over nine years by changing the way payments to “disproportionate share” hospitals are calculated met the same fate. Finally, a lawsuit brought by the Association of American Medical Colleges, the American Hospital Association, and nearly 40 hospitals killed any hope of saving about $800 million a year by eliminating “site-of-service differentials” that pay doctors employed by hospitals more than physicians with independent practices—even when the physicians are delivering the same services in the same offices.

- 2019 was also the fifth year in which the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) failed to implement legislation enacted in 2014 which sought to save a paltry $200 million over 10 years by discouraging physicians from needlessly ordering expensive CT scans and MRIs. Regulations were supposed to take effect in 2018, but more than two dozen medical societies complained, so the Trump administration delayed them until January 2020.

- Big Pharma is currently working overtime to kill the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act, which would penalize drug companies for raising prices faster than the rate of inflation. Although the bill has bipartisan support, knowledgeable observers say it has no chance of achieving the 60 votes needed to pass the Senate. Indeed, the bill may not make it out of the Senate Finance Committee, since 13 of the 15 Republican senators on the Committee oppose it.

- The health care industry has also turned back efforts to audit its charges. Medicare Advantage plans, which are paid based on how sick their enrollees are, don’t want Medicare to know whether they are exaggerating enrollees’ illnesses, so they have fought off or watered down efforts to audit their reports. CMS is already unenthusiastic about auditing the health care system: for the past four years, it has canceled Medicaid eligibility audits, and “has never taken meaningful actions to minimize improper payments from the [Medicaid] expansion.

Medicare for All is also certain to drive up spending by generating an enormous surge in demand for medical care. The bills pending in Congress promise soup-to-nuts coverage for free. Premiums, deductibles and copays are supposed to vanish. If that happens, prodigious consumption of medical services will be inevitable.

The fundamental problem is that Medicare for All’s supporters have cause and effect reversed. They think Americans need universal comprehensive coverage because health care is expensive. In reality, we spend too much on health care because we rely so heavily on third parties—Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers—to pay our bills. In 1960, when patients paid about $1.73 out of pocket for every $1 paid by an insurer, health care spending per capita was $165. In 2010, when patients paid out 16 cents for every insurance dollar, spending per capita was $8,400. And in 2017, when the ratio was 14 cents out of pocket for every insurance dollar, spending per capita was $10,740. The more we rely on third party payers, the more we spend. Because the full-on, government-run, single-payer plans introduced by Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren will reduce out of pocket costs to zero, they will drive spending to new heights.

Paying out more than it takes in

What about the various “public option” proposals, including the less-sweeping version also known as “Medicare for all who want it”? They will open the doors to the treasury wider, too. Although supporters assert that premiums will cover the public option’s costs, that’s not how government-funded health care works. Public programs are heavily subsidized with taxpayers’ dollars. A typical one-earner couple pays $70,000 in Medicare taxes during the working spouse’s lifetime and gets $427,000 in benefits in return. The premiums for Medicare Part B, which pays for doctors’ services, originally covered 50 percent of the cost, but today cover only 25 percent. Premiums for Medicare Part D (which covers prescription drugs) are so low that the program depends on general tax revenue for more than 70 percent of its funding.A public option is sure to follow the same path, paying out far more in benefits than subscribers pay in as premiums. Proponents will want millions of people to sign up, and the easiest way to get them to do so will be by making the public option a steal. Elizabeth Warren has already said that the public option she wants to create in the course of transitioning to Medicare for All “will be immediately free for nearly half of all Americans.” Interest groups like AARP, which wants a subsidized buy-in option for near-seniors, will pressure Congress to support the program with taxpayers’ dollars too.

Like the advocates of Medicare for All, the public option’s proponents also hope to save billions of dollars by paying doctors and other providers at Medicare rates or something similar. (Medicare pays hospitals about half as much as commercial insurers, and it pays doctors about 20 percent less.) We’ve seen this movie before, however, and that’s not how it ends. If threatened with drastic payment cuts, doctors and hospitals will fight back in the public arena. They will generate widespread panic by threatening to close their doors. That’s what happened during the managed care revolution in the 1990s, and the backlash was ferocious. Americans like their doctors, and hospitals have huge traction in their communities. When providers rose up against managed care, state legislators introduced more than 1,000 bills designed to protect patients and calm consumers’ fears of losing control of their health care. The public option’s proponents are seriously underestimating the industry’s power to rally the public.

If neither Medicare for All nor the public option is an attractive means of controlling health care spending, what is? We believe that the spending crisis will disappear when Americans pay for most medical services directly, the same way they pay for everything else, and reserve insurance for catastrophes. Homeowners’ insurance kicks in when houses are destroyed by fires or other calamities that rarely occur. Homeowners pay out of pocket for predictable non-catastrophic expenses, like maintenance, remodeling and new paint. Health insurance should work the same way.

More concretely, a national health reform that truly wants to address spiraling costs should take the following steps:

Increase retail options. Let retailers like Walmart, CVS Health, Costco, and the Surgery Center of Oklahoma that operate on a cash basis offer a full range of medical services. They have demonstrated their power to make primary care, blood tests, medications, hearing aids, eyeglasses, surgeries, mental health counseling, dental cleanings and telemedicine cheaper. Lower prices will help everyone, and poor people, who are especially sensitive to costs, will benefit the most. Competition from retailers will pressure traditional providers to be more consumer-friendly, too.

End tax subsidies. Eliminate the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance and all coverage mandates. These steps will encourage (but not require) people to switch from expensive comprehensive insurance to much cheaper high-deductible catastrophic care insurance, and to pay for most treatments themselves. The entry of tens of millions of new cash-paying health care consumers into the market will cause the retail sector to expand, and the pressure to lower prices will grow.

End Medicare as we know it. Replace Medicaid, Medicare and other programs that provide in-kind benefits with a single program, modeled on Social Security, that gives poor people cash plus an insurance policy covering catastrophes. If combined, the budgets of existing social welfare programs would more than suffice to bring all Americans above the federal poverty line. Cash transfers would also enable people to pay for food, housing, education and other social determinants of health that affect wellbeing more than medical treatments do.

Will these arrangements work perfectly? Of course not. But they will vastly out-perform the existing system, which is known to waste almost $1 trillion a year. And unlike Medicare for All and the public option, these proposals will transform the health care system without raising taxes or putting the economy at risk. When consumers pay for most medical services directly—the same way they pay for nearly everything else—the health care spending crisis will disappear.

https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/no-medicare-all-wont-save-money