Moments Without Truth

Making sense of online discourse in the age of Trump

Six months ago, when I first started writing this piece, things were simple. I wanted to write about The Discourse—the loose set of reflexes and affronts that function as the invisible lingua franca of the social-media world. If I couldn’t chart The Discourse’s deeper psychic roots and many ungainly twists in any definitive way, then I might at least make an earnest attempt at anatomizing the phenomenon head-on.

But achieving any sustained critical distance from The Discourse is a bit like having a sea creature describe the nature of life in the desert. For those of us who are badly, incontrovertibly online, The Discourse isn’t just a feature of everyday life. It’s the muck we swim in, the rot that conditions us, the frame that dictates the contours of many of our ideas and interactions. When we log on, The Discourse stares us in the face only for an instant—that instant in which we get some perspective on how simultaneously all-encompassing and false it is—before it sucks us in. Whether you ride high, get dragged under, or simply manage to stay afloat, The Discourse churns on, sustained by a frenzy of posts and overheated takes but somehow never descending into chaos.

To some degree, The Discourse is a formula. It always starts with a moment, a point so obvious that Twitter leverages Moments as a key part of its platform. (The company’s attempts to corral, and at times even govern, The Discourse would be sinister if they weren’t so feckless.) In the vernacular of actual Twitter usage, the (lowercase m) moment can represent any number of things, including but not limited to a breaking news item, a poorly worded or inflammatory public statement (often in the form of a tweet), a viral piece of journalism, a new poll, a fraught single image, incriminating video, or the release of a high-profile film, book, or album. The Discourse’s only real rule of thumb is that for a moment to have any legs, it has to be a bad thing. The Discourse has little use for the affirmative, and good things fizzle out quickly. As long as it’s (to take a partial, but broadly representative sample) shameful, offensive, idiotic, rude, humiliating, repulsive, violent, evil, inept, self-indulgent or self-satisfied, retrograde, or naïve, The Discourse can work with it. These judgments make no appeal to cohere as part of a larger moral or aesthetic framework. What matters is the identification of that bad thing. That’s the spark.

The Discourse is not picky. As long as there’s something there to glom on to—almost any sociocultural raw material will do—the takes will begin to fly immediately. Instead of letting things sink in, listening closely, or waiting for a full picture to develop, we weigh in reflexively. Some moments are devised entirely to enable engagement. Others that might warrant more careful consideration get jammed into the confines of The Discourse because the content of a moment is less important than the opportunity for engagement that it affords. Either way, what’s set into motion unfolds predictably from there. The impact of the moment registers as a chorus of “wows” or “hell nos” before being either endorsed or decried along fairly predictable ideological lines. These initial stages of outrage are then typically followed by a critique of the critique that can range from contradiction to backhanded assent—hand-wringing over whether the moment was really worth all the fuss, or even instantaneous nostalgia for the wild ride that has, at this point, become perfunctory. Then, unceremoniously, the moment is discarded and forgotten as another takes its place. Its usefulness has been exhausted, and all that remains is a barely recognizable husk.

The Discourse often seems to have a will of its own—a property implicit in the very designation of it as discourse, i.e., a kind of speech-act bridging the distance between intention and expression. It barrels through moments as if hell-bent on sustaining itself. But to view it as somehow beyond our control is to once again abdicate agency—as well as responsibility for its existence. This isn’t as simple as the mundane (and true-enough) claim that, after all, we make the posts.

The Discourse exists because, on some level, we want it to, which means we get something out of it. We talk about our relationship to The Discourse in highly personal terms. We feel deep shame for taking part in it. It fills us with regret. We lament what it says about us that we feel compelled to participate. We tell ourselves that we can, and maybe should, stop at any time—the proverbial “logging off”—but we always come back, at first reluctantly, and then, like self-deluded addicts believing they can quit any time they like, we soon find ourselves swept up in it all over again. Somehow, despite all of this, no one ever stops to wonder what possibly elusive something keeps us coming back. Attributing it to inertia, boredom, or technology is a lightweight cop-out, not to mention that all of those are just screens for deeper issues. As much as The Discourse creates the illusion of collective enterprise, and possibly even political usefulness, it has also been fueled by individual fantasy.

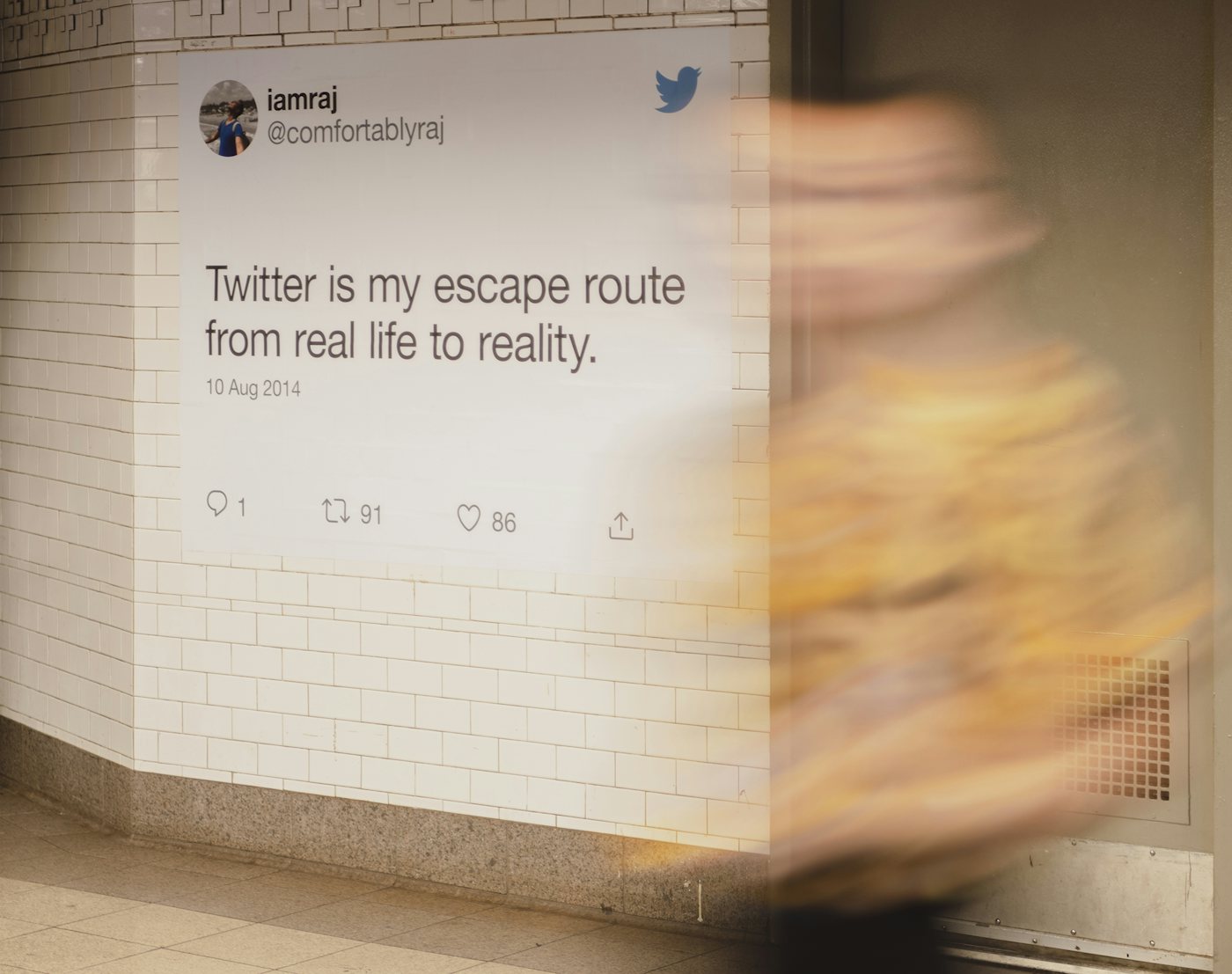

At the heart of The Discourse is always one simple, presumed truth: that tweeting is a meaningful act with some connection to the off-line world. Talking about stuff on Twitter was, from the beginning, understood as a way to engage with events. When a thing happened, you took to Twitter to voice your take. Calling it a “platform” has ironic significance, since Twitter is both a megaphone and a product forever circumscribed by the discursive boundaries (and possibly even the pecuniary concerns) of the tech industry.

The Discourse is inseparable from Twitter, to the point where the two can be used interchangeably in some circles. Twitter is far from the most popular social media platform; on sheer numbers, Facebook trounces it. Even then, a sizable chunk of its users rarely tweet, and plenty of those who do have little interest in, or even familiarity with, The Discourse. But what Twitter may lack in raw numbers, it makes up for in influence. It’s a platform favored by real-world power brokers in politics, entertainment, and media. If Facebook embodies the nameless, faceless, diffuse will of the masses, Twitter represents the stomping ground of elites whose real-world clout imbues this platform with a kind of cultural authority that rival social-media outlets lack. This both legitimates the content of some of these users’ tweets—this isn’t just some random account talking—and allows them to amplify and elevate narratives in distinctly old-fashioned ways. This all conspires to give the impression that Twitter, instead of merely commenting on the world, can actually influence it in a far more targeted way than, say, a haphazard bundle of Facebook ad buys during a major election. To put it another way: The president of the United States tweets compulsively in wildly free-associative fashion, usually several times a day. He is present on Facebook and Instagram in name only.

While Twitter wielded a certain amount of power, or at least cultural sway, it lacked a form. That was part of its charm. This convoluted state also hampered Twitter’s utility for creating and reinforcing narratives. The platform was a decentralized free-for-all that actively discouraged traditional hierarchies and highlighted individuality, which made it somewhat resistant to larger agendas, institutional agendas, or groupthink.

The arrival of The Discourse changed all of this. It turned Twitter into a mechanism, albeit an uncontrollable, at times erratic one, that could be harnessed in the service of something bigger than the individual. It’s impossible to pinpoint exactly when The Discourse took off in earnest, but, as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said about obscenity, you knew it when you saw it. Its inception signaled a seismic shift in the way larger agendas came home to roost online. If you want to get conspiratorial about it, the platform, as a tech company, always had certain built-in political or ideological aims, and certainly its archindividualism had smacked of Silicon Valley’s techno-libertarian streak. But it was The Discourse that rendered Twitter intelligible and semi-predictable. It domesticated online expression, turning it into a vehicle for institutional will.

At the same time, though, this articulation of power was masked by The Discourse’s nimble propensity for making Twitter itself seem like a more streamlined, appealing commodity. The platform had previously promised users the opportunity to make themselves heard. To what end, and in what, if any, context was an open, and perhaps unanswerable, question. Giving them something to participate in—a process that they could inhabit in something more than a purely rhetorical sense alongside other individuals—made screaming into the void feel less pointless and lonely. It also solidified the fantasy that Twitter was about anything other than itself. What The Discourse chose as its specific object was less important than the fact that there was now some fixed object that users could rally around, and that object existed only insofar as there was a process that ritualized its mass reception. And if the act of tweeting mattered, then the subject behind it was similarly affirmed. Innumerable users have thought “I tweet, therefore I am” was an original, clever idea—but this mundanity makes it evident just how much Twitter became a form of self-actualization, of feeling like individual Tweeters could assert themselves in some meaningful way via The Discourse.

Much is often made of the role Trump’s use of Twitter played in his rise, or how he has successfully turned the logic of Twitter into the logic of the world, or at least that of the peculiar geopolitical reality that he both inhabits and creates online. We are all victims of his use of the platform, held hostage by his whims, conditioned by his impulsive rantings. At the same time, the central fantasy of The Discourse has proved remarkably seductive in the Age of Trump, to the point where many of the same people who decry the effect that Twitter has had on the world are existentially, and also frequently professionally, beholden to it. The Age of Trump has also been The Discourse’s golden age, because Trump himself is a constant source of shocking and idiotic content, and, as the president of the United States, he is able to similarly vulgarize politics or the cultural conversations that pass for politics these days. But he also provides an inescapable lens on the world, whereby The Discourse is sustained by its appetite for Trump-like content. The world behaves like Twitter. But just as important, our relationship with the world has been transformed by The Discourse, to the point that it’s hard to say where perception stops and reality begins.

While The Discourse’s formal origins are lost in the mists of time, it was in the wake of the 2016 election that it really took off. Ambient, uncertain dread was the prevailing mode as the country awaited a future that was expected by all, regardless of their political allegiance, to be transformative and like nothing that had happened before. (This is largely what happened with Obama’s election as well, but with the sides switched.) When the eventual shock wore off, people were desperate for an explanation. But there was nobody to provide one. Institutional authority took a richly deserved pillorying in 2016. Pundits had failed to predict the election’s outcome and underestimated Trump’s appeal; that Trump himself had run aggressively on his own alleged anti-institutional, outsider cred put an even finer point on the death of expertise.

With the usual suspects off licking their wounds, a vacuum opened up and was filled by emboldened nonexperts who didn’t so much have something to say—no one really did—as they embodied a continual need to say something, because to not do so would be to admit that much of what we thought we knew was in total free fall. In terms of the basic process of arbitrating a consensual version of reality, this was an exceedingly hazardous slippery slope. Before long, everyone succumbing to the thrall of The Discourse—which is to say, potentially everyone, period—was an expert, or at least could feel safe in the assumption that no one would disqualify their takes based on a lack of expertise.

But this wasn’t a flattening of hierarchies of the sort long hymned in Silicon Valley reveries of the online demos. No, it was more a destruction of the authority that nonhierarchical systems are meant to delegate outward. Nobody knew a thing, and nothing was correct—but utter nihilism could be staved off if enough people yelled loudly enough. What should have been a time for self-reflection instead found everyone being louder than ever, and only listening to others insofar as they provided grist for “engagement”—a term most fully realized through conflict or enmity. It was self-esteem as a mode of self-preservation; if you couldn’t feel good about the world, you could at the very least feel good about yourself.

To be sure, there was concern about what Trump would do as president. But for many, there was a deeper anxiety at play. Privileged, comfortable people became convinced that this presidency would directly make their lives worse, and this surmise upset them tremendously. They felt strangely helpless, as if all the things that had formerly protected them had vanished. It was unclear what they thought would happen, or why they assumed there would be a great upheaval. Was it because Trump’s vulgarity and unpredictability felt dramatically new? That hardly seemed likely. Still, the specifics of what was about to go down mattered far less, it seemed, than the blow that election had dealt to their own self-image as duly credentialed arbiters of the common good. They wielded a certain amount of power in the world—and Trump had won even though they, and many other powerful people, opposed him. Now they were lost, and Twitter became a clearinghouse for their mounting sense of desperation.

Supposedly, things were better before Trump’s inauguration, and there has been nothing but upheaval since. Those who had decried pre-Trump normalcy—most notably, those who had called out Barack Obama’s innumerable lapses into neoliberal complacency—will tell you, often smugly, that things had always been bad and the unenlightened are only now coming around. (Somewhat suspiciously, it looks as though the ranks of this “I told you so” set have swelled over the past two years.) But even these seers have to admit that the mass exodus from steadied ignorance of our national politics has had a destabilizing effect, in large part because Trump’s election sent shock waves through the very sectors of society that had been perfectly comfortable before it.

It’s worth noting that many of the people most distressed by Trump presidency could have continued living their lives as if nothing had changed. Instead, they’ve allowed it to overrun their day-to-day existence. Current events, politics, and social issues have gone from niche Twitter subjects to a daily feature of online conversation and obsession; how could they not be? If the pre-Trump age permitted the president’s trademark cruelty, stupidity, and senselessness to hide in plain sight, these ugly features of our common life are now rudely thrust in our face at every turn. When racism, sexism, corruption, and inequality are laid bare—and coarsely embodied by Trump himself—it becomes harder for anyone with a conscience to deny them, or ever to feel truly immune from them.

It has also, in certain circles, become de rigueur to care about the world, or at a minimum to be appalled by Trump. At least for the moment, disengagement is no longer socially acceptable. But this relationship to what can be broadly described as “politics” isn’t just a newfound refusal to turn a blind eye to the world. The Discourse was a coping mechanism masquerading as a moral necessity, a form of “empowerment” passed off as an exercise of a new kind of power.

The Discourse works as coping mechanism in at least three different ways, all of which depend on the trope of perpetual crisis. It tempers a chaotic reality by furnishing a sense of order. No matter how unpredictable the news gets—here, the Trump effect is undeniable—we can metabolize it via The Discourse’s familiar cadence. It’s a source of comfort—a ritual that, despite ostensibly signifying panic, provides a day-to-day buffer from the intrinsic senselessness of the world around us.

But The Discourse isn’t intended to calm us. It’s a thrill ride, an exhilarating romp through politics and culture that, at its worst, reduces its subject matter to a form of entertainment. Conventional wisdom holds that the sheer horror of the Trump presidency makes it impossible to look away, and that to do so would be irresponsible, or at least socially unacceptable. What no one wants to admit is that The Discourse provides a shot in the arm that relieves the tedium of the everyday. The Trump-ification of politics is as much about what we want from the news as how we process it; The Discourse works as a proxy for mood-enhancement that feeds individualistic self-absorption rather than solidifying collective opinion or will. It’s no accident that “mood” is one of the online world’s more prominent tropes. Despite its nonstop immersion in bad news and even worse vibes, The Discourse is a way of making us feel better about both the world and ourselves.

But this dynamism isn’t just a diversion. It miscasts politics as exciting, facile, and instantly gratifying, when every substantive form of action is laborious, time-consuming, and at times grindingly tedious. When done right, governance is a drag. Organizing is a long slog. Even the meaningful analysis that The Discourse often mimics requires some measure of grit and persistence. Real gains don’t happen overnight, nor are they readily apparent every step of the way. If you believe that things are in fact very bad and irrevocably broken, it follows that fixing them will not, and should not, be easy. The alternative is to submit to The Discourse, which has turned “this is not normal” into a new kind of normalcy: a temporary, suspended state that will have to suffice until the external world once again conforms to this notion.

The Discourse may feel good in its own perverse way. But allowing yourself to feel discomfort, the experience of being alienated and out of joint, is not only a wake-up call. It’s what sustains those who have embraced what politics actually consists of. This unpleasantness isn’t swept under the rug or converted into something readily digestible. Instead, it’s confronted head-on, stared down, and challenged. The outcome is uncertain. But what should distress us is not the possibility of failure. We should be most wary of the illusion of success.

The Discourse, which superficially represents political engagement, has in fact always been a way of withdrawing from political reality. Rather than confront and address political challenges, it provides a vehicle for people to feel better about themselves by deflecting their discursive energies away from the real matter at hand.

At the same time, however, The Discourse was always presumed to be about something. It was a way to process and assimilate unpleasant information that depended on pretending that some work was being done to attack the substance of that information at its point of origin. Or, to put it another way: The Discourse had to be about something in order to make something go away, possibly by substituting something else in its place. While the Age of Trump has brought its fair share of horror and absurdity, the tendency to describe it as perpetual crisis or trauma frequently says more about how things are being perceived, and who is perceiving them, than it does about some objective condition. The whir of activity comes not from conditions in the world but from the ceaseless mechanism by which unpleasantness can be laundered and made fathomable, even manageable. As bad as the Age of Trump has been, it has also succeeded in granting people an entirely new, and altogether more thorough, way to distract themselves, while maintaining the illusion that they are in fact more engaged than ever.

In the months since I first started thinking through all of this, I’ve picked up on a marked shift in the way The Discourse works. While the mechanism remains the same, the relevant content no longer lands the way it once did. The usual grandstanding rings hollow; the earnest notes feel forced; and the blanket condemnations clunky and overused. Maybe the novelty has worn off. Maybe The Discourse has begun under its own steam to exact a toll and thus to become a cognitive burden rather than an illusion of engagement. Maybe its efficacy as an outrage-delivery system was compromised by one too many pieces of especially pointed bad news. Maybe the ceaseless deflection from the world finally succeeded in creating an insurmountable distance, undoing the whole premise that The Discourse was about something other than itself.

Whatever the reason, The Discourse has curdled, going back and forth from faux-earnest to fully earnest in announcing its therapeutic aims, and then succumbing at length to a feckless and wholly empty pursuit sustained by inertia. When it makes us feel anything, it’s only because it allows us to feel nothing. Instead of insulating us from the world by pretending to do the opposite, The Discourse is now the experience of being nowhere and belonging to nothing. All that’s left to do is fall back on self-referential byways and go after likes and retweets as an impoverished means of filling the void it’s created.

As The Discourse has cannibalized itself, it’s also done away with any pretense of seriousness. Dunking on people is now the prevailing mode of Twitter interaction, and if anyone tries to change the world via a series of tweets, there’s a good chance that they will get laughed off the stage. Irony poisoning has gone from an in-joke to the only reasonable response to a daily routine that is slowly sucking the life out of all of us. You can see this in, for example, the change in how The New York Times’ op-ed page is discussed these days. At one point, it was a source of outrage. Bari Weiss got called out for clumsy, appropriative ethnic rhetoric, and the Times was lambasted for having climate change denier Bret Stephens on staff. There was real concern that the likes of Weiss and Stephens were dangerous, that the ideas they put out there could have a harmful effect and therefore had to be headed off at the pass and roundly discredited. The paper of record was going down a dark path, the Twitterfied resistance proclaimed, and only The Discourse could save us. This all also had something to do with Trump’s vendetta against respectable journalism, the subsequent fetishization of it by liberals, and the subscriptions that the Times or The Washington Post succeeded in wringing out of them, which in turn has allowed both papers to thrive in the midst of a dying industry. The Times’ reporting was seen as a force for good, while its op-ed page was often cast as evil, a by-product of the separate editorial oversight of both operations. (It’s perhaps indicative of the mounting take-based confusion at the heart of The Discourse that this managerial distinction appears to be eroding, to judge by the paper’s puzzling decision to publish a news-breaking excerpt from Robin Pogrebin and Kate Kelly’s book on U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings in its Sunday opinion section, sparking in the process no end of outrage on the Twitterfied right and left alike.) In any event, the broad online tendency to interpret the Times’ journalistic identity in split-screen fashion elides certain fundamental truths about the centrist coalition and the fallacy of two-party polarization; in terminal flight from any disconsolate, outrage-dampening thought on this scale, Twitter instead framed the repeated high-profile miscues and editorial lapses of James Bennet’s pundit shop as a problem that badly needed repair.

Meanwhile, the Times soon grasped that it had a potential marketing boon on its hands: Columnists such as Stephens and editors like Weiss were potent clickbait. The last thing their employer wanted to do was give up the traffic they created. In other words: Far from undermining the Times’ credibility or hurting its bottom line, Stephens and Weiss (and to a lesser extent, David Brooks, Thomas L. Friedman, and other easily lampooned Times opinion makers) were good for business because people hated them. At some point, however, the dance became ritual, and from there it was but a short step for it to become farce. The recognition that the op-ed section pushed a steady stream of disastrously conceived ideas out into the world took a back seat to the sheer obtuseness of Stephens and Weiss, both bad writers whose ideas and arguments typically play out at the level of high school English papers, and undistinguished ones at that. Holding them up as villains in some grand morality play began to feel like a misguided, if not outright foolish, use of collective mental energy. Indeed, making them the enemy was actually a lamentable self-own. And predictably, the anger they’ve elicited gave way to pure mockery, potshots replaced critique, and the realization that these pundits were almost always wrong, and were indeed cynically all but programmed to be so, took a back seat to how dopey and half-baked their work was. Dunking on them both was a reflexive burst of endorphin-charging smugness, and soon became shorn of any political overtones whatever. The now-infamous “bedbug” episode, pitting Stephens against a heretofore obscure academic Twitter user, had nothing to do with the so-called marketplace of ideas, but what Stephens perceived as a personal attack. That he was so thin-skinned and vindictive made for great content. At the same time, the episode was also entirely illustrative of how The Discourse had evolved. Stephens melted down because he got called a name, which is what happens now because there’s nothing else for him, or for most of the rest of us, to do.

Bret Stephens and Bari Weiss were never going to single-handedly bring about the fall of humanity; having gone to war with them as if the fate of America was at stake is, in retrospect, more than a little embarrassing, especially when the Times has so plainly gamed this dynamic to enhance its bottom line. But while these confrontations were largely simulated for the benefit of The Discourse, using them now as nothing more than an opportunity to reel off still more jokes and online snark is a self-evident dead end. The withdrawal has now become explicit, and the elaborate work The Discourse once did has given way to a simple means of distraction.

We have no excuse—and yet we use this very fact as an excuse more baldly than ever before. The Times op-ed section has become an inside joke—a development that’s only possible because we have stopped pretending that it’s anything other than irrelevant. Yet abandoning this fantasy has also obscured politics. It’s far less entertaining, but also far more urgent, to acknowledge that the Times’ op-ed page highlights the centrist-to-center-right coalition that’s nearly as much of a threat to any nascent left movement in our politics as the out-and-out fascists further to their right. The real political problem is clear, and yet instead of talking about it, we just keep on dunking.

It’s as if we’re so ashamed that we once pretended to care that now we’ve given up on the possibility of actually caring. And until this changes, until we take a definitive turn toward meaningful engagement, The Discourse will keep going strong. It’s there, among other things, to make us feel as if we don’t have any other choice.