Humiliated Emmanuel Macron is presiding over a country that has lost its raison d’être

Whatever became of France? Once the most beautiful, brilliant and civilised country on earth, it is now caught in a seemingly irreversible spiral of decline. The French know it — a survey last year found that 61pc believe the country is in decline — but they feel powerless to prevent it.

The mood is sullen, resentful and angry. Violence simmers just below the surface, as in the yellow vest protests four years ago. Those who dare to look behind the crumbling facade of the French state will find a nation in existential crisis.

The crisis has countless causes. At its heart, however, is the despair of a people who have been deceived for so long that they no longer believe anything their leaders say — even if they tell the truth. The mood is crepuscular, at times almost apocalyptic, as those who have been kept in denial come to terms with a present that mocks their hopes for the future. There is barely a glimpse of la gloire with which they associate the rapidly receding past.

Earlier this year, when the fate of France hung in the balance during the presidential election, Emmanuel Macron made short work of his rival, Marine Le Pen, by depicting her in their TV debate as Putin’s poodle. He was duly re-elected by a substantial majority.

Yet there was none of the jubilation that had greeted his first victory in 2017. This time the French no longer took their President’s promises seriously: he and his entourage were seen merely as the lesser of two evils. Within a month, his party had lost control of a National Assembly dominated by the far-Left and the far-Right.

Macron had been humiliated: a president in name only, his office deprived of the power and the glory that the architect of the Fifth Republic, General de Gaulle, had intended.

Since then, the ageing wunderkind has sought to regain the trust of his people by admitting what they all know: that their country is no longer the pride of European civilisation, but a nation ill at ease with itself, unequal to the task of preserving its own identity, let alone its revolutionary legacy as the global champion of the rights of man.

Much of France is in a perpetual state of panic or rage about uncontrolled immigration and its own profoundly alienated Muslim population.

Last week, in a televised interview, Macron defended his record on law and order after the sensational murder of Lola, a 12-year-old Parisian girl, but for the first time conceded an inconvenient truth: “If we look at crime in Paris today, we cannot fail to see that at least half of the crime comes from people who are foreigners, either illegal immigrants or those who are waiting for a residence permit.”

Even a year ago, Macron would have vehemently condemned such views from one of his Right-wing rivals. That he now says it himself is a sign of his desperation. For it implies not only that the French state has lost control of its borders, but that it is failing to integrate the rapidly growing proportion of the population whose origins lie in the former French colonies.

Paris is, after all, a microcosm of France. The lawless anarchy of the banlieues that surround the capital, amounting almost to low-level terrorism, is mirrored in almost every other city. The graffiti, vandalism and filth that disfigure the streets of Paris are ubiquitous elsewhere too.

The decaying infrastructure, the hideous monuments of avant garde “starchitects”, reflect the extinction of Parisian stylishness in art, dress and manners. And the conflagration that almost destroyed the Cathedral of Notre Dame in 2019 symbolised the collapse of Christianity in what was once a land more devoted to Our Lady than any other

The decline of France manifests itself in many ways. Underlying the political malaise is an economic one that has been accelerated, but not caused by, the shocks of the Covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The long history of French dirigiste governments of Left and Right, which have prioritised state control over free enterprise, has bequeathed a centralised economy that seems unable to adapt to global headwinds.

Take the car industry: it still employs 800,000 workers, but it has been plunged into what Le Monde last April called “an existential crisis”, with sales down 17pc on 2021. Since then, the cost of energy has left the likes of Renault, Peugeot and Citröen struggling to survive. A nation of mechanical pioneers, traditionally obsessed with the open road, has fallen out of love with the automobile. Yet the captains of industry behave like rabbits caught in the headlights.

It is the same story with nuclear power, which provides 70pc of French electricity. The failure to replace ageing infrastructure has left more than half of the 56 reactors out of service as the worst winter in living memory approaches.

EDF, which operates the plants, has been nationalised and, for the first time in decades, France is importing more energy than it exports, only narrowly avoiding blackouts so far. For the foreseeable future, the country has not only been overtaken by Sweden as Europe’s leading electricity exporter, but has lost its vaunted reputation for energy security.

French agriculture, too, is losing ground to foreign competition, especially in beef production. Over the past 20 years, the amount of beef produced in France has fallen 9pc to 1.4m tonnes, according to Eurostat.

Meanwhile food inflation rose to 11.8pc last month, with fresh products rising by nearly 17pc year on year. While state subsidies have kept overall inflation below the EU average, this policy of bribing consumers with their own money to mask the true picture is unsustainable in the medium term.

The tax burden in France is among the highest in the developed world. The French tax to GDP ratio, at 45.4pc, is the second highest in the OECD. The UK figure is 32.8pc. Put another way, the French government spends almost 53pc of GDP; the UK Government about 10pc less. So although the British are paying the highest taxes for 70 years, compared to the French we are allowed to keep much more of our incomes.

Youth unemployment in France also remains stubbornly high, at 15.6pc compared to 9pc in Britain. Meanwhile, GDP growth will amount to 2.5pc this year, according to forecasts by the International Monetary Fund, while the UK’s economy is expected to grow by 3.6pc.

However bloated by its confiscatory fiscal policies and despite its protectionist trade policies, the French state has failed to prevent the descent of its industrial regions into terminal decline. The equivalent of the “Red Wall” in England is to be found in Northern and Eastern France, while the rural hinterland is equally depressed. Opinion polls now give Le Pen’s National Rally nearly 50pc, with most of these protest voters concentrated in the rust belt regions and la France profonde.

Around 3m French homes are empty, or 8.2pc of the total, the national statistical office revealed last year. That is up since the turn of the millennium, when the figure stood at 6.9pc. In some communes, the vacancy rate is higher than 20pc.

The old problem of a centralised bureaucracy stifling the free market means that in contrast to Britain and the US, the decline of old French industries has not been compensated by the rise of new ones. Instead of cutting taxes and red tape in order to retain enterprising young people and attract investors, France has aped the least attractive of “Anglo-Saxon” tastes.

Despite having created the very concept of the restaurant, the French are more inclined to grab a “McDo” for lunch than any other Europeans. But the vulgarity of McDonalds and other aspects of American commercialism are by no means the worst of French transatlantic imports.

Like their US counterparts, academics and politicians have lately been at war over the spread of woke identity politics, which President Macron says risks “breaking the republic in two”.

After the beheading of schoolteacher Samuel Paty by an Islamist two years ago, an acrimonious row broke out within French intellectual circles over the education minister’s claim that “Islamo-Leftists” on university campuses were turning a blind eye to radicalism.

Frédérique Vidal warned some lecturers were seeing “everything through the prism of their desire to divide, split, designate the enemy”.

Wokery, with its totalitarian intolerance and inbuilt philistinism is a deadly threat to the life of the mind everywhere, but perhaps especially in France. Why? Because France has been here before.

As in May 1968, the universities are the weak link. Then as now, the self-entitled and self-indulgent attitudes of a generation of students threaten to overwhelm their timorous professors. Older French generations are just beginning to realise how bewitched they were by the intellectual gurus who seized power in the chaotic aftermath of 1968.

Perhaps the cleverest, most cynical and most pernicious of these Pied Pipers was Michel Foucault. His books and lectures undermined the moral foundations of French history, society and intellectual life. Only now, decades after his death in 1984, is France gradually coming to terms with the fact that it allowed its collective mind to be befuddled by an evil genius — who was also an alleged predatory paedophile, according to a contemporary.

Like so many of the post-1968 amoralists, Foucault was the son of a strictly Catholic middle-class family and he received an excellent education. What underlies many of the present French discontents is the loss of all these things. The Church has largely lost its place in society, the bourgeoisie has been hollowed out, the family has disintegrated and the education system has abdicated its role in encouraging intellectual pursuits.

The decline of the French schools at all levels is especially distressing to those who knew them in their heyday. The lycées and the grandes écoles were highly competitive and unashamedly elitist, but they achieved their purpose of equipping the leadership of France to a superlative level. After 1968, however, the rot set in and has since affected every part of the system.

Macron closed the École Nationale d’Administration, the elite finishing school for the country’s leaders and bureaucrats that he himself attended, last year amid claims it had become yet another institution to become captured by elite groupthink. It was originally set up by Charles de Gaulle in 1945 as a way of breaking the hold of the upper-classes over France’s levers of power.

Macron, a typical product of the system, has unfortunately presided over an acceleration in its decline. France does poorly in the PISA (Programme for International Student Achievement), ranking far below the UK or Germany. France slipped down the rankings for reading skills from 19th to 23rd in 2018. The UK ranked 14th. Just one French university (PSL Paris) made it into the top 50 in the world, according to the Times Higher Education rankings.

One consequence has been the decline of French science. This was revealed by the pandemic, when Macron had to admit that his country was unable to produce its own Covid vaccine — unlike the US, UK and Germany. The French authorities also took much longer to vaccinate their population than their British counterparts.

Such facts are no surprise. France has never been a pure meritocracy: its rigours have always been tempered by connections, corruption and class. But the educational and economic impoverishment of the bourgeoisie has damaged professions such as the judiciary, medicine, the military and the media. The quality of politicians, too, is strikingly low. Just as Macron is no De Gaulle, so there are no journalists of the calibre of the General’s great critic Raymond Aron. French public life is a moonscape of mediocrities.

Domestic decay has been accompanied by geopolitical decline. Under Macron, France has failed to support Ukraine against Russian aggression and has lost influence in its North African backyard. Who could forget the contrast between Volodymyr Zelensky’s unfeigned admiration for Boris Johnson and his exasperation when he found himself embraced by Emmanuel Macron?

Only months earlier, the French president had been forced to defend the withdrawal of his country’s troops from former colony Mali after a decade fighting jihadist groups. His decision, prompted by a falling out with the ruling military junta, left allied British peacekeepers with no air support, and opened the door to greater influence from Russia, which has sent private military contractors to the region.

Even the Germans, whom the French have hugged all the closer since Brexit, are brutally detaching themselves from a partner whose interests are increasingly divergent.

Intergovernmental meetings and a joint visit to Beijing have been cancelled, while a Macron-Scholz lunch last month resolved none of the outstanding issues. Germany under Scholz is going its own way, dashing Macron’s hopes of leading the EU after Angela Merkel’s retirement. The newer member states are contemptuous of the French President’s attempts to broker peace with Putin; most simply ignore his posturing.

The same sense of a global power in decline applies, only more so, to the realm in which France once excelled: high culture. Last month the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to the 84-year-old Annie Ernaux. Like the better-known Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard, Ernaux writes “autofiction”, obliging the reader to submit to the immersive trivia of her daily existence.

Such a vicarious experience of mundanity evidently fascinates a growing readership, but it is hardly the stuff of which the great literature of a self-confident nation is made. Rather, Ernaux’s works are saturated in the solipsism and nihilism of a nation in decline.

A subtler French writer than Ernaux, Michel Houellebecq, published a far more prophetic novel earlier this year. Anéantir (“Destroy”) is set in 2027, as Macron leaves office. His vision of France is grim: stricken by poverty and unemployment, it is a rapidly ageing society. Hence his focus is on fatal illness. Unlike Ernaux, whose depiction of her mother’s dementia is shockingly cold-blooded, Houellebecq’s writing about the end of life is suffused with humanity.

Yet even Houellebecq sees no sunlit uplands for France. For him, as for most of his compatriots, Macron cannot come clean soon enough about the failures of leadership that have reduced France to such relentless economic, social, political and educational decline. The pessimism of the country’s greatest writer speaks volumes about a nation gripped by the politics of cultural despair.

Houellebecq’s last testament is his valedictory elegy for a France that has lost its raison d’être. Under Macron, the French have reversed Descartes’ Cogito, ergo sum. Now it should read: “I no longer think, therefore I no longer am.”

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/11/06/how-france-became-trapped-spiral-chaos-decline/

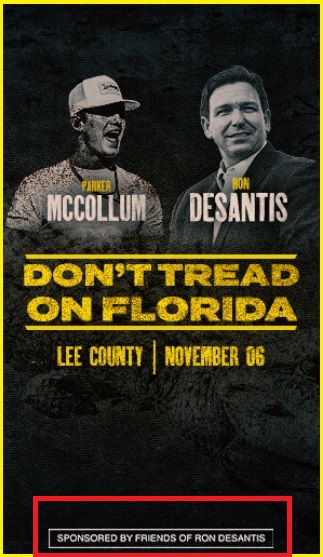

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis will not be at the

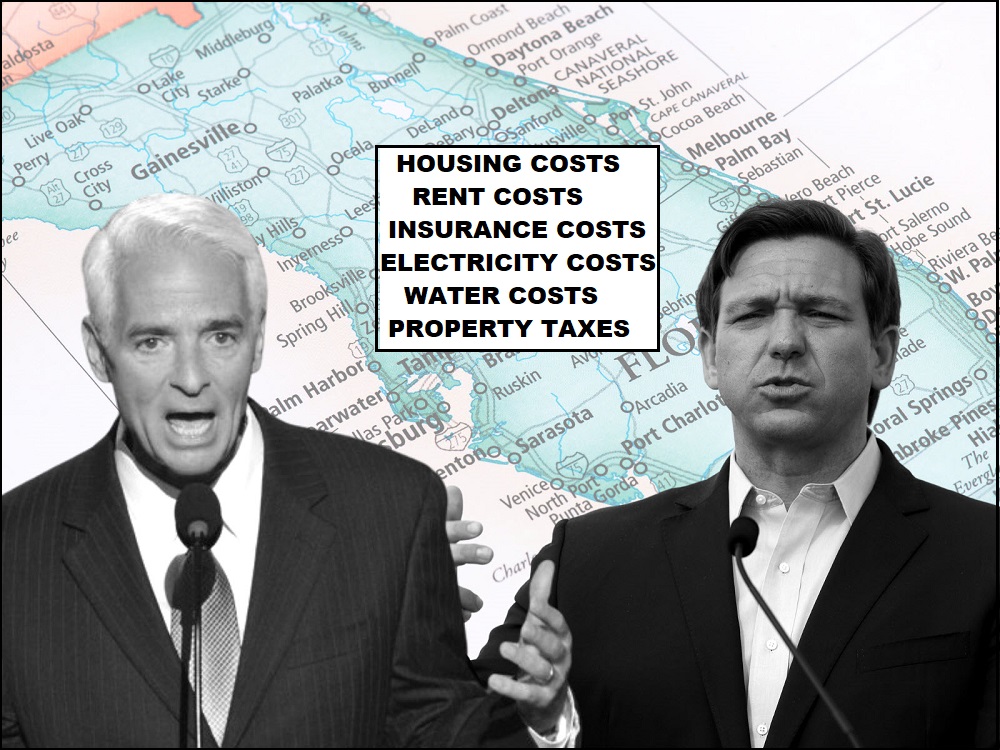

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis will not be at the  To emphasize… Governor Ron DeSantis is a good governor, a good manager, well liked and should be well supported by the Florida voting base. There are several large issues for Florida that voters are counting on Governor DeSantis and the Florida legislature to tackle quickly in 2023.

To emphasize… Governor Ron DeSantis is a good governor, a good manager, well liked and should be well supported by the Florida voting base. There are several large issues for Florida that voters are counting on Governor DeSantis and the Florida legislature to tackle quickly in 2023.