No man is an island, except for George Will.

When I was but a young collegiate firebrand making waves on campus in

the distant days of two-thousand-eighteen, my academic advisor—a

kind-hearted boomer liberal in the history department—found himself

worried about my situation. I was too smart, he insisted, to write the

way I did. (On the contrary, I promise I am exactly dumb enough to write

like this.) “You can either be some shock jock,” the professor warned

in a fatherly tone, “or you can be George Will.”

Well, I thought to myself silently, I sure as hell don’t want to be George Will.

A year or so later, in a less paternal moment, he accused me publicly

of the thoughtcrime of “rank individualism.” I was a bit confused,

given that the comment (and my less-than-voluntary resignation from the

university’s newspaper) had been provoked by a broadside against the expressive individualism of the school’s gay-activist community.

Both

moments came to mind this week as I read an unusual column by the very

pundit whose name my advisor once invoked. Having revisited an essay by

one of the liberal right’s chief philosophers, Michael Oakeshott, Dr.

Will thinks he has stumbled on the key “to the United States’ distemper

in 2021.”

From right and left, Will says, individualism is under

attack. On the left, “critical race theory subsumes individualism,

dissolving it in a group membership—racial solidarity, which supposedly

has been forged in the furnace of racist oppression.” At the same time,

“U.S. ‘national conservatives,’ who are collectivists on the right,

recoil against modernity in the name of communitarian values, strongly

tinged with a nativist nationalism and with a trace of the European

blood-and-soil right.”

I am not a national conservative, for reasons I have previously explained.

Yet Will seems to have sloppily assumed that the label applies to

anyone on the right who is not a liberal, so I will take the liberty of

counting myself among those criticized.

Both groups, the

post-liberal right and the progressive left, are what Will calls

“modernity’s enemies.” Will writes that “modernity’s greatest

achievement, which was the prerequisite for its subsequent achievements,

was the invention of the individual.” Before the advent of modernity,

Persons

knew themselves only as members of a family, a group, a church, a

village or as the occupant of a tenancy: “What differentiated one man

from another was insignificant when compared with what was enjoyed in

common as members of a group of some sort.”

This began to change in Italy with “the break-up of medieval communal life.” As the historian Jacob Burckhardt would write,

“Italy began to swarm with individuality; the ban laid upon human

personality was dissolved.” Individuals detached themselves from

derivative group identities, becoming eligible for individual rights

grounded in the foundational right to an existence independent of any

group membership.

This is a ludicrous overstatement, inspired by a cursory reading of Burckhardt’s The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Burckhardt, an art historian writing in the middle of the nineteenth century, suggested that:

In

the Middle Ages both sides of human consciousness—that which was turned

within as that which was turned without—lay dreaming or half awake

beneath a common veil. The veil was woven of faith, illusion, and

childish prepossession, through which the world and history were seen

clad in strange hues. Man was conscious of himself only as a member of a

race, people, party, family, or corporation—only through some general

category.

This is not only untrue but fundamentally

unbelievable. The son of a Protestant minister, Burckhardt sits squarely

in the tradition of Reformation historiography, which relies by nature

on a cartoonish reduction of the Middle Ages to “faith, illusion, and

childish prepossession.” No one can be expected to believe that medieval

man was actually unable to think of himself as a distinct human person.

The truth behind the lie is that medieval man did not think of himself first as an individual.

This

is because he was not a moron. He knew, as a matter of fact, that he

belonged to things bigger than himself, that his identity could not

possibly be established without reference to the external world. Will’s

“foundational right to an existence independent of any group membership”

is an absurdity, especially so in a species whose every individual

necessarily belongs to at least one definite group on being brought into

existence. As far as I know, George Will was not created in a lab.

More

than inevitable, though, the fact of identity’s dependence on

interpersonal relationships is eminently desirable. It is a very strange

kind of conservative who celebrates “the break-up of…communal life”

(medieval or otherwise) as one of the great developments of human

history. Beyond strange, it is impossible: The conservative’s interests

necessarily transcend the individual, not least of all because

tradition, the act of handing something down, hinges on connections

between people. Individualist conservatism is a contradiction in terms: For whom could something not held in common possibly be conserved?

The

achievement and preservation of the common good is intergenerational,

“a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those

who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born,” in

Edmund Burke’s famous words. The world of Will’s imagination must be one

in which nobody is ever born and nobody ever dies.

The

conservative, meanwhile, lives in the real world. He not only sees that

all people enter the world with bonds—to family and tradition, to place

and neighbor—but celebrates that fact; he seeks to strengthen those

bonds and the joy secured by them. Mindful of the ravages of time, he

pursues that security not just for a moment but well beyond his

lifetime, taking hold of something handed down and ensuring its

preservation after he has gone. He knows that the atomic man is a

vicious fiction, a deception whose success would loose every bond and

wipe out every attendant joy. And so, as his critics worry, he

“recoil[s] against modernity in the name of communitarian values.”

Will

ends his individualist manifesto with an aphorism from Paul Valery, a

gifted French poet with an astonishingly dull mind: “Everything changes

except the avant-garde.” It is perhaps not the coup the column’s author

thinks to admit his opponents are the only ones who have stood fast

through the ages.

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/individualism-is-the-enemy/

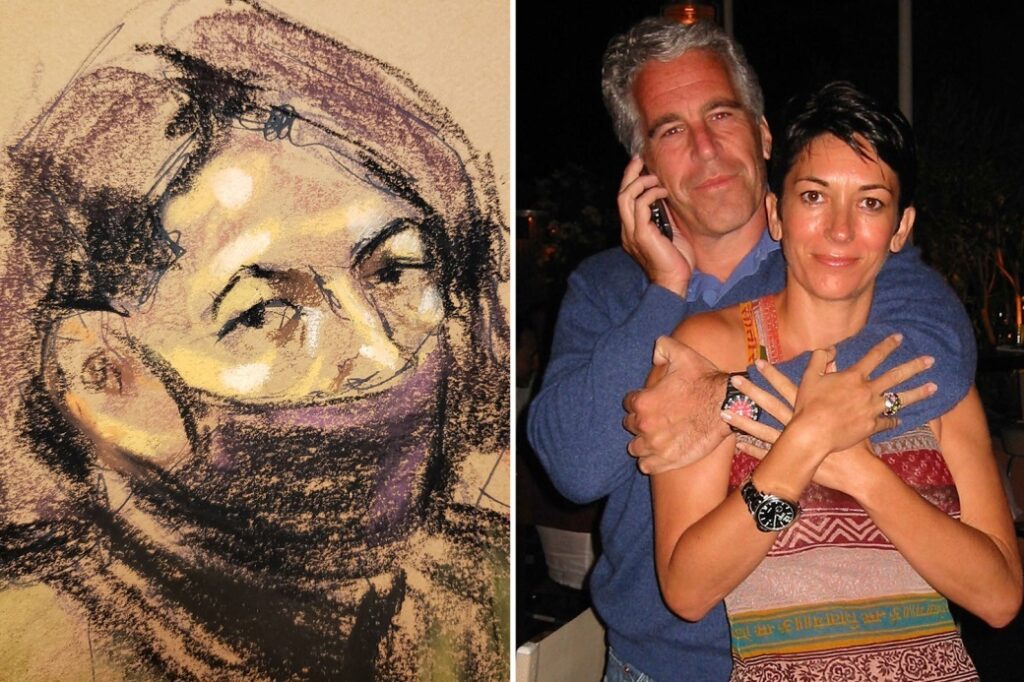

NEW YORK (AP) — The British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell was convicted Wednesday of luring teenage girls to be sexually abused by the American millionaire Jeffrey Epstein.

NEW YORK (AP) — The British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell was convicted Wednesday of luring teenage girls to be sexually abused by the American millionaire Jeffrey Epstein.

Deep state operative Mary McCord (not named but transparently visible) and administrative insiders

Deep state operative Mary McCord (not named but transparently visible) and administrative insiders