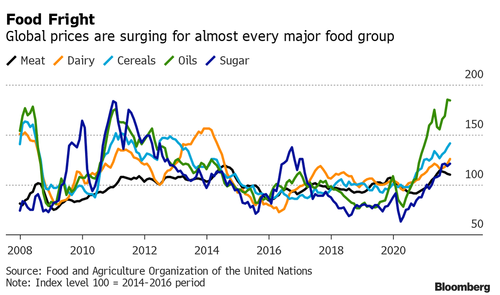

Across the world, households are experiencing an exponential rise in food inflation.

This holiday season, from Brazil to China to European countries to the

US, households will pay near-record prices for food, which begs the

question: Are households able to afford traditional food, or will they resort to substitutes to save money?

"You

might be able to trade down on some things; instead of the high-priced

turkeys or steaks, you might consider something less expensive on that

side of the dinner table," Curt Covington, senior director of

institutional credit at AgAmerica Lending, which lends money to farmers,

told Bloomberg.

"But there's no escaping it: Everything on the holiday table "is just going to be more expensive," Covington said.

For

example, working poor Americans have had trouble affording essential

goods amid rapid inflation. A staggering 6.8% surge in consumer costs is

the highest in four decades, making things like food unaffordable because wages haven't kept pace with inflation. The same is happening for households worldwide

With that in mind, households are likely to substitute popular holiday foods with low-cost items. There's even a chance that some might resort to eating bugs and worms.

European member states certified house crickets, yellow mealworms, and grasshoppers as food fit to be sold at supermarkets.

The bugs will be sold in frozen, dried, and powdered forms and will be packed with nutrients and low-cost, according to Bloomberg. Earlier this month, the World Economic Forum published two articles explaining

how people must get used to eating bugs. Those who can no longer

afford meat, such as ham or turkey, and other traditional holiday foods

will come to find a new substitute. Bloomberg provides examples from

across the world of how food inflation crushes holiday cheer.

Brazil: Amazon Fish Replace Pricey Imports

Fatima

Santos describes her family's planned Christmas Eve supper in 2021 in

one word: lean. Neither cod nor turkey—traditional centerpieces in many

Brazilian homes for the holidays—will make the cut this year, the

41-year-old unemployed hairdresser said while combing the shelves for

deals in a Rio de Janeiro supermarket. "Egg is the new steak in our

home. Even rice and beans are super expensive," she said. That's hardly a

seasonal specialty, but the staple dish might grace more holiday tables

like hers as meat prices become increasingly hard to stomach.

Although

the country is one of the world's largest producers of agricultural

commodities, soaring demand abroad and a weak local currency are making

exports more profitable, leaving less Brazilian-grown food for

Brazilians at home. At the same time, this year's extreme weather—the

worst drought in a century followed by an unprecedented frost—severely

damaged the nation's crops, stoking inflation. Think tank Getulio Vargas

Foundation calculates beef prices are up about 15% in the last year,

while chicken costs have soared more than 24%.

Grocery chain Zona

Sul has been trying to stock its shelves with more local products so

families can avoid the worst of the inflation. Traditional Norwegian cod

is still available in the weeks leading up to Christmas, but the store

is also pushing Amazon fish pirarucu for half the price. With sparkling

wine imports delayed due to container shortages, the chain is

discounting regional alternatives. "As purchasing power diminishes,

people are looking for secondary brands," said the chain's executive

director, Pietrangelo Leta.

Priscila Santana, a professional chef,

usually sells rabanadas—a dessert resembling French toast—around the

holidays. But she's had to boost prices this year by more than 10% on

rising costs for bread, milk and eggs, plus the gasoline required to

even get to the store. Despite starting sales several weeks earlier this

year and accepting both credit cards and company-issued meal tickets,

she's still seeing lower demand. "I expect to sell 20% less this year.

Some of my clients had to give up the rabanadas to buy their lunch

instead.

China: Stockpiling Sends Costs Soaring

There's

plenty of food to go around in the world's most populous country, the

Ministry of Commerce insists. But that hasn't stopped Chinese households

from stocking up—and in some cases, hoarding—following a confusing

advisory from the government in early November that encouraged people to

restock essentials ahead of winter, stoking fears of travel

restrictions, virus outbreaks, extreme weather or worse.

"Usually

one family only needs to store one bag of flour, but now they're buying

two or even three bags. Of course prices will increase," said one

shopkeeper who's been selling noodles, dumpling wrappers and Chinese

pancakes for almost 30 years. Speaking from behind his stall in a market

in Beijing, he asked to only be identified by his family name, Zhou.

"The more families hoard flour, the higher prices will go."

The

25-kilogram (about 55-pound) bags of flour he buys from his supplier are

about 30% more expensive than a month ago, now costing more than 90

yuan ($14). But Zhou has raised his own selling price by less than 20%,

even as the winter solstice—Dongzhi—nears, boosting demand for

traditional delicacies like dumplings and noodles. "My costs have risen,

but I can't really increase prices or I'll lose customers," he said.

UK: Turkey Farms Pay Up for Labor

"There

isn't a product that we use on this farm that hasn't gone up," said

Becky Howe, a third-generation farmer, as she watched workers guide a

flock of turkeys to an open barn on the last day of slaughtering at the

John Howe turkey farm outside Kent. That includes the cost of steel used

to construct the barns, chopped straw for bedding, corn feed, gas,

packaging cartons and even wax for the automated plucking line. The farm

wasn't anticipating such inflationary pressure when it boosted the size

of this year's flock by 25% and, for the first time ever, started

rearing geese, too.

The greatest headache has been finding enough

workers during November and December, the farm's busiest time of the

year. Most of its employees are foreigners, who come to the country on

temporary visa permits; the farm has boosted pay this year to retain

staff. It has raised the price of its turkeys by 8%, but its own costs

have gone up more. "The price increase hasn't covered everything and

we've had to absorb as much as we possibly could," Howe said. "We don't

want to pass on too much and scare people away from buying our turkeys."

Worried

about rising prices—plus a shortage of UK truck drivers that will only

exacerbate the squeeze—grocers say some families in London started

buying their Christmas turkeys as early as October this year. The demand

for smaller birds is particularly high as virus fears temper optimism

that extended families will be gathering again this year after a 2020 in

lockdown

Romania: Priced Out of the Pig Slaughter

In

the Romanian countryside, the Orthodox celebration of Saint Ignatius on

Dec. 20 has followed a traditional script for centuries: Buy a pig from a

trusted farmer, slit its throat, burn the skin, and clean the carcass

with help from friends and family at the break of dawn. Every part of

the animal—from the legs to the fat to the intestines—are then

transformed into dozens of dishes to feed a household's extended family

at Christmas, New Year's and every meal in between.

At least, that

used to be the custom. This year, more families will just snag some

supermarket sausages on their way home from work and call it a day, said

Adi Rusu, a 40-year-old farmer from the village of Posta Calnau. Rusu's

family has been growing pigs for 40 years, but with feed and

electricity costs through the roof, risks of a deadly swine fever

outbreak and customers increasingly opting for easier options, his

family's talking about whether it's even worth the hassle. It's hard for

neighbors to justify paying as much as 1,500 Romanian lei (about $340)

for a local pig, a 50% hike over the last four to five years. At the

same time, Covid travel restrictions that keep many working Romanians

abroad mean downsized dinners—and little incentive to cook enough pork

to eat for at least seven straight days.

"It's becoming obvious we

can't eat three times more than in a regular week at Christmas," said

Marioara Mihalcea, the director of meat company M&R in Iasi. "You

know you can always find fresh meat on the shelves."

Rusu only had

six pigs on offer this year, about a fifth of what he'd normally sell,

after many of the piglets died at birth, but he decided supplementing

with more piglets from commercial farms to turn a profit of only 400 lei

(about $90) apiece just didn't make economic sense this year. Would-be

customers are "not buying from someone else; they're going to the

supermarket," said Rusu, who picked up animal farming from his father.

"Those who know how to prepare it are slowly passing away, and the young

are not interested in learning."

US: Cookie Season Takes a Hit

Americans,

eating more butter than ever before, will find it costs them more than

their waistline this holiday season. Once vilified for saturated fat,

butter has become popular again as shoppers embrace high-fat diets,

driving per capita consumption to 6.3 pounds in 2020, the highest in

data going back to the Ford presidency. Butter consumption typically

peaks in the fourth quarter, thanks to all the holiday cookies, mashed

potatoes and other full-flavored traditions that grace the table. It's

also soaring in price.

Spot wholesale prices for Grade AA butter

are up about 40% from this time last year to more than $2 a pound.

There's plenty of milk to make it, but packing and shipping have been a

challenge amid widespread labor and materials shortages. Grassland Dairy

Products in Greenwood, Wisconsin, recently raised its prices for

supermarkets for the first time in four years. President Trevor

Wuethrich cited rising cardboard expenses, trucking issues and its own

decision to hike hourly wages in September in order to retain trained

employees.

Some households may make the switch to vegetable-oil

spreads, like margarine, to cut costs, though those are rising in price,

too. Dina Cimarusti, owner of newly opened Sugar Moon Bakery in

Chicago, just paid 40 cents per pound more than usual for butter in

early December. For her, subbing it out isn't an option: It's an

important ingredient for many of her home-style pastries including

scones, cookies and cakes.

"It's not just butter," she said. "Even

my produce prices have gone up significantly since I opened," said

36-year-old Cimarusti, whose storefront debuted in September. "Unless I

raise my prices, I'm obviously losing money." For now, she's holding

pat. "I was just going to wait it out," she said, clad in a green apron

and jeans, weighing pound-blocks of butter before dumping them into a

large steel mixer for molasses cookies. "I just try to keep it

affordable."

Simply put, inflation increases food

insecurity that will dramatically reshape traditional holiday dishes.

Some may resort to eating bugs and worms this year.

https://www.zerohedge.com/commodities/food-inflation-grinch-spoils-christmas-cheer